This week Jupiter and Saturn are low in the southwest during the chilly December dusk. When this month began, they were separated by 2.1 degrees.

But in the days that followed, they have been slowly approaching each other; getting closer by about 0.1 degrees each day on their way toward the long-awaited "great conjunction" next Monday evening (Dec. 21). Their inching closer to each other will be further enlivened by the passage on Wednesday and Thursday evenings (Dec. 16-17) of a foreground waxing crescent moon.

Both planets are moving eastward with respect to the stars, with the slowest, Saturn, initially in the lead and Jupiter, the faster planet, in the rear. Thus, December began with a stubby diagonal line of Saturn and Jupiter (from upper left to lower right) along the ecliptic — that imaginary line on the sky that marks the annual path of the sun, as well as where the moon and planets also wander.

Related: 'Great conjunction' of Jupiter and Saturn will form a 'Christmas Star' on the winter solstice

With each passing day the pace of excitement has been quickening as the gap between Saturn and Jupiter has been rapidly shrinking.

And now we have arrived at the "home stretch" of their long-awaited rendezvous.

Two planets in the twilight joined by the moon

No doubt these two worlds have called attention to themselves to many, even to those who normally don't pay much attention to the sky, low in the southwest twilight sky shortly after sunset. Alas, it will soon be time to bid a fond adieu to "Big Jupe" and its retinue of Galilean satellites, and the showpiece of the solar system, the magnificent ringed planet, Saturn. We'll have about another month before they both begin to disappear into the sunset.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And on Wednesday evening, we will still be able to enjoy the sight of Jupiter and Saturn, now separated by just 0.5 degrees, but now also joined by a lovely waxing crescent moon, nearly 2.5 days past new phase; appearing as a skinny arc of light just 6% illuminated by sunlight. On that evening, the moon will appear to hover 5.5 degrees below the "dynamic duo."

Your clenched fist at arm's length measures about 10 degrees, so on this night, expect to see our nature satellite hovering about a "half fist" below our double planet. Of course, be sure, in advance of your attempt to make this sighting that there are no tall trees or buildings to obstruct your view of this "celestial summit meeting." After all, all three will be lowering rapidly as the sky darkens.

The show will run from sunset to about 6:30 p.m. local time. But the best time to see all three will come about 45 minutes to one hour after sunset against the deepening cobalt blue of evening twilight.

The old moon in the arms of the new

Look carefully and see if you can make out the entire disk of the moon, with the dark portion immediately straddling the bright slender sliver. The rest of the lunar disk will seem to dimly glow with an eerie bluish-gray coloration. This is called Earthshine.

From the lunar surface, our Earth undergoes phases just like the moon, except they are opposite to the lunar phases we see. We call this effect "complementary phases." So, on Wednesday (Dec. 16), an astronaut standing on the dark part of the moon would be looking skyward and seeing a nearly full Earth in the sky; sunlight reflected off of the Earth would provide the only illumination for the surrounding lunar landscape and that's the faint blue-gray light that you're seeing from here on Earth.

In binoculars or a small telescope, the moon appears almost three dimensional; almost like some translucent Christmas ball. For thousands of years, humans marveled at the beauty of this "ashen glow," or "the old moon in the new moon's arms." Leonardo da Vinci was the first to figure out what this dim glow really was.

Viewing with a telescope

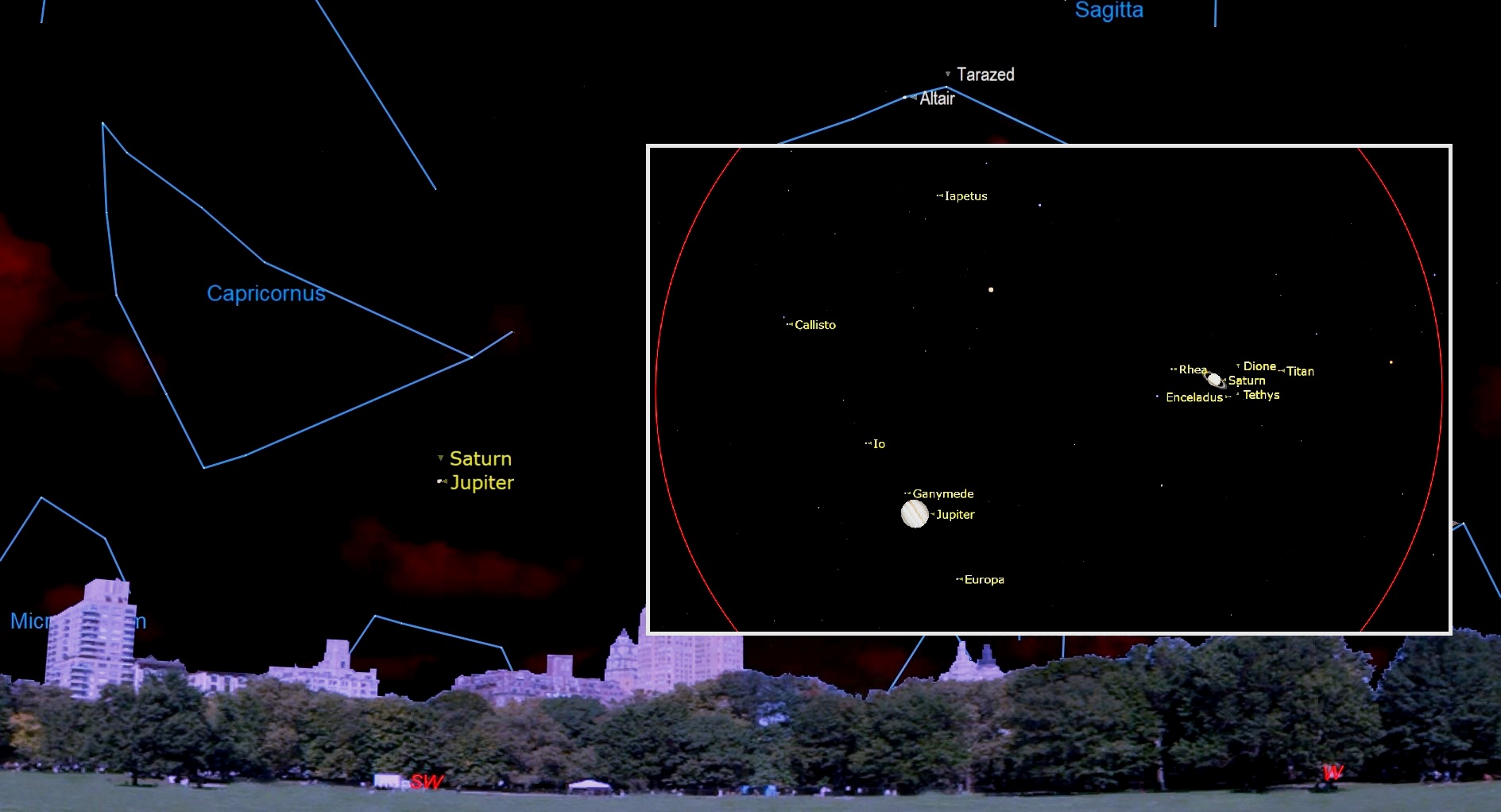

And if you would like to see more moons, train your telescope on Jupiter that night, for three of the four of the famous Galilean satellites will be visible. On one side of Jupiter, you'll see its volcanic moon Io (closest to Jupiter's disk) and second-largest moon, Callisto. On the other side of Jupiter will be Ganymede, Jupiter's largest moon. As for Europa, it will be in transit, crossing in front of Jupiter.

Saturn, the solar system's version of the "lord of the rings," appears to the naked eye as a solitary bright "star" shining with a sedate yellowish-white tint immediately to Jupiter's upper left, though appearing less than one-tenth as bright as Jupiter.

Of course, you can only see Saturn's famous rings with a telescope, though some might catch a glimpse using steadied (or image-stabilized) high-powered binoculars or small spotting scopes. But to get a definitive view you'll need an eyepiece magnifying at least 30-power. Larger instruments will provide more pleasing images. Through a 6-inch (15 centimeters) telescope at 150 power, the view is quite dramatic; with an 8-inch (20 cm) at 200 power, the sight is absolutely stunning.

Get your views in as early as possible, since our atmosphere is so much more turbulent near the horizon. So, as Saturn descends the southwest sky, its image will appear to "boil" or become somewhat distorted.

Moving on

On the following evening (Thursday, Dec. 17), the crescent moon will have widened to 13% illuminated and will have moved about 9 degrees to the left (east) of Jupiter and Saturn; still an eye-catching sight. In the nights that follow, the moon will head on an easterly course against the background stars and will be pretty much by itself.

For the owner of a telescope the moon is perhaps the most interesting of all sky objects, because it's close enough to be seen really well. Even a simple pair of 7-power binoculars will show definite features on its surface. Check the area especially around the line that separates light and dark (called the "terminator") and you'll see craters and other lunar features stand out in bold relief because they're partially in shadow. With each passing night, more of the lunar surface will become illuminated and the crescent will gradually widen. It will arrive at "half," or first-quarter phase, on the night of the great conjunction (Dec. 21) with the full moon occurring on Dec. 29.

Related: How to observe the moon (infographic)

How often?

There has been considerable discussion of late about how rare it is for Jupiter and Saturn to come as close to each other as they will — just 0.1 degrees, or 6 arc minutes — next Monday. In a previous column I mentioned that the last time was in 1623 (though not easily visible due to their close proximity to the sun). Prior to that was in 1226, some 794 years ago.

But is it just as rare to see two planets, other than Jupiter and Saturn, come so close together? Surprisingly, the answer is no. In the table below, I compiled a list of cases in which two of the five brightest planets approach within 6 arc minutes or less and far enough away from the glare of the sun to be readily seen in a dark or twilight sky. The time frame runs from 1975 to 2065.

| Date | Planets | Separation | Time of day |

|---|---|---|---|

| June 5, 1978 | Mars, Saturn | 6 arc min | Evening |

| Sep 10, 1991 | Mercury, Jupiter | 5 arc min | Morning |

| Dec 21, 2020 | Jupiter, Saturn | 6 arc min | Evening |

| Jan 30, 2048 | Venus, Saturn | 6 arc min | Morning |

| Sep 27, 2049 | Mercury, Mars | 2 arc min | Morning |

| June 7, 2057 | Venus, Saturn | 6 arc min | Morning |

| Dec 18, 2064 | Mars, Jupiter | 6 arc min | Morning |

Over a 90-year interval there are seven exceptionally close approaches between two bright planets. That averages out to one about every 12.9 years, although we've had to wait 29 years since the last really close encounter (Jupiter with Mercury in 1991) and yet only 21 months will elapse between the next very close encounter in 2048 (Venus and Saturn) and 2049 (Mercury and Mars).

Next Monday, when Jupiter and Saturn are separated by only 6 arc minutes, using a telescope with magnification of 100-power, you'll be able to see both: Saturn with its famous ring system and Jupiter with its cloud bands and Galilean satellites, simultaneously in the same field of view!

As to whether the two planets might appear as a single star, take note of the first conjunction listed in our table: June 5, 1978, when Mars and Saturn were separated by a similar distance. I observed that remarkable event first hand and I could clearly separate both planets with my naked eye. However, some near-sighted observers might see Jupiter and Saturn appear as one merely by removing their eyeglasses.

What more can we say? Good luck and clear skies!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.