The Kardashev scale: Classifying alien civilizations

The Kardashev scale is based on how much energy a civilization uses.

What might we find: little green men or microbes? How might we find them: radio waves or strange chemicals in the planet's atmosphere? Something no one has even thought of yet?

Over the decades, scientists considering the possibility of life beyond Earth have pondered what such life might look like, how humans might be able to identify it from afar — and whether communication between the two worlds might be possible.

That thinking has included developing classification systems ready to fill with aliens. One such system is called the Kardashev scale, after the Soviet astronomer who proposed it in 1964, and evaluates alien civilizations based on the energy they can harness.

Related: 13 ways to hunt intelligent aliens

What is the Kardashev scale?

The Kardashev scale is a classification system for hypothetical extraterrestrial civilizations. The scale includes three categories based on how much energy a civilization is using.

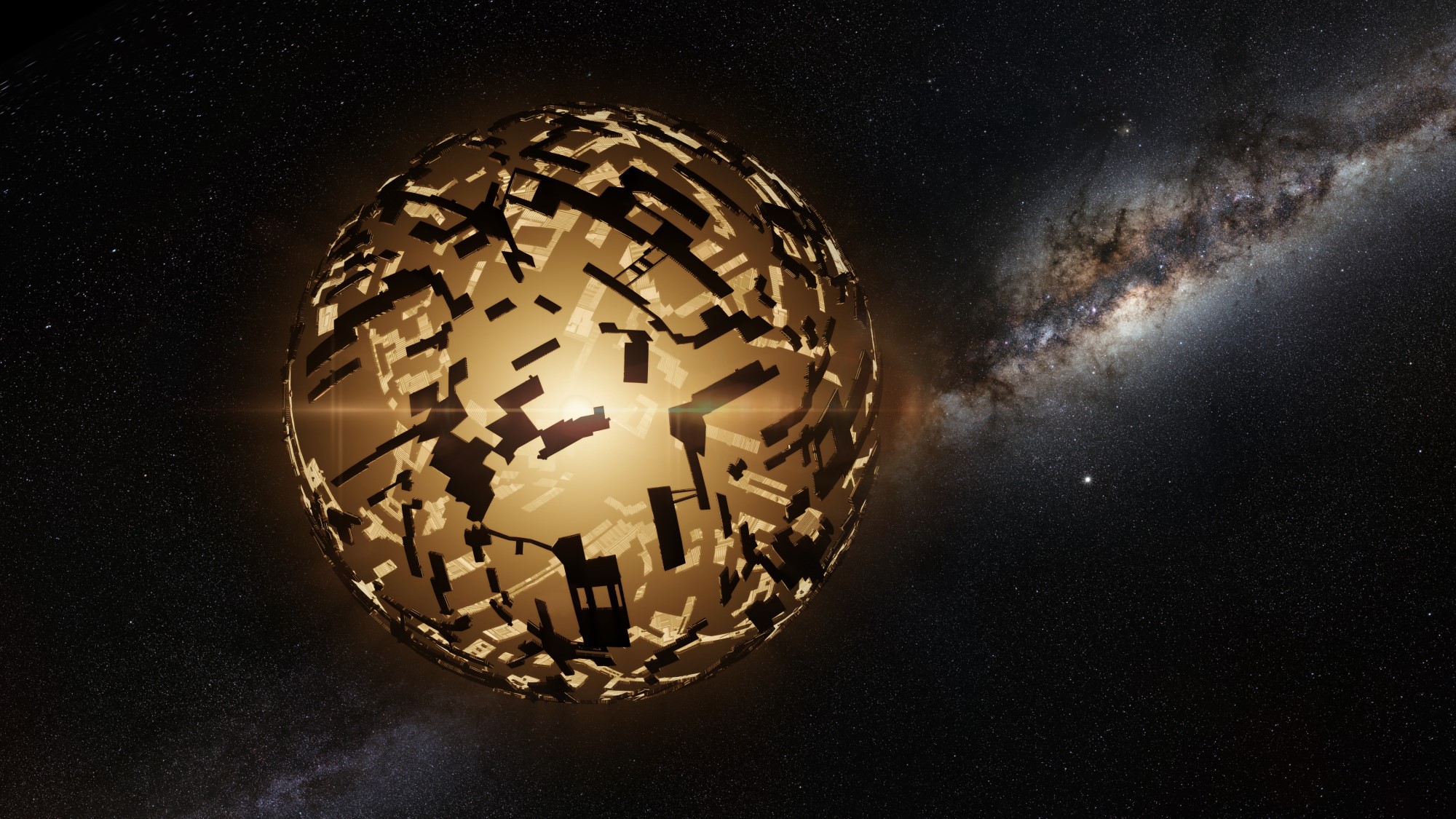

Kardashev describes type I as a "technological level close to the level presently attained on the Earth," type II as "a civilization capable of harnessing the energy radiated by its own star" and type III as "a civilization in possession of energy on the scale of its own galaxy."

Each type also includes a numerical cut-off for the energy involved, but those weren't arbitrary cut-offs. "He used things that are easy to visualize," Valentin Ivanov, an astronomer at the European Southern Observatory who has built on Kardashev's work, told Space.com. "I'm almost tempted to say it's a publicity stunt, these comparisons that he uses to make it easier for people to understand."

Kardashev's scale is included in a five-page paper published in 1964 and called "Transmission of information by extraterrestrial civilizations." (The paper was originally published in Russian, but an English translation was published the same year.)

Although the scale is what caught people's imaginations, "Transmission of information by extraterrestrial civilizations" focuses on calculating how powerful a light signal from any point of the universe would need to be for radio scientists at the time to detect it. This value is also the numerical cut-off for the energy use of a type II civilization.

Who was Kardashev?

Nikolai Kardashev was a Soviet and Russian astrophysicist who died in 2019. Kardashev was roughly contemporary with early search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) leaders like Frank Drake, who published his famous equation three years before Kardashev's paper; Giuseppe Cocconi and Philip Morrison, who predicted what an extraterrestrial signal might look like; and Freeman Dyson, who pondered ways alien civilizations could surpass the limits of a planet.

In addition to his scale, Kardashev developed a technique called very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI), which uses a global network of radio dishes as one radio telescope the size of Earth. Perhaps most famously, VLBI is used by the Event Horizon Telescope to observe black holes, including producing the first ever black hole image, published in 2019.

Kardashev also proposed supplementing Earth-based network VLBI observatories with space-based telescopes to increase its observing power even more. He advocated for the Russian mission RadioAstron, which launched in 2011, to do just this sort of work, according to a review of VLBI developments.

Where are humans on the Kardashev scale?

If working only within the basic categories, humans are a type I civilization on the Kardashev scale (a civilization with a working Dyson sphere structure harvesting its star's light would qualify as type II). Literally speaking, because humans have not harnessed the equivalent of the entire energy of Earth, other scientists have said that humans rank as more like a 0.7.

How does the Kardashev scale relate to SETI?

Scientists and science-fiction thinkers alike have referenced Kardashev's scale throughout the decades, and they have both praised and criticized the system.

One benefit of Kardashev's scale is that it focuses on a civilization's detectability by humans, rather than its technological advancement writ large, much of which might come in ways that astronomers cannot observe.

However, it has also been dubbed overly simplistic, both in considering only one characteristic and in its few, broad categories. (The iconic astronomer Carl Sagan argued that Kardashev's categories represented too vast of leaps in energy consumption and proposed dividing each into smaller categories — type 1.1, type 1.2, etc.)

The Kardashev scale's focus on infinite growth as a measure of progress has also become difficult to swallow. It was rooted in the dominance of SETI at the time by radio astronomers, Ivanov said. "For radio astronomers, bigger is better," he said. "Intuitively, for them, more power meant a more advanced civilization." Yet over the decades, as humans have begun to experience the global chaos caused by our tapping of fossil fuels, the risks of idealizing constant energy-hunger have become clear.

Kardashev's paper also speaks to the continuing core tension of the search for life beyond Earth: is it more valuable to look for biosignatures, changes to a planet that only life at some scale from microbes to manatees can cause, or for technosignatures, signals like radio waves that rely on not just life, but intelligent life skilled in noticeable technologies? "There is an ongoing argument which of the two is more important," Ivanov said.

But while Kardashev's work focuses exclusively on technosignatures, it acknowledges the biosignature side as well and suggests that each search can inform the other. "The discovery of even the very simplest organisms, on Mars for instance, would greatly increase the probability that many type II civilizations exist in the galaxy," he wrote. "Radio astronomical searches could of course play a decisive part in resolving this problem."

The Fermi Paradox: Where are the aliens?

The Kardashev scale's legacy

Nevertheless, the true heart of the paper that includes Kardashev's scale was a broader statement about SETI. "It's often forgotten that what he did was to estimate the technical feasibility of interstellar communications," Ivanov said. "The classification that he came up with is almost an afterthought of that paper."

And in the paper's conclusion, Kardashev argues that even if the calculations don't hold up, the potential reality of interstellar communications should.

"We should like to note that the estimates arrived at here are unquestionably of no more than a tentative nature," Kardashev wrote. "But all of them bear witness to the fact that, if terrestrial civilization is not a unique phenomenon in the entire universe, then the possibility of establishing contacts with other civilizations by means of present-day radio physics capabilities is entirely realistic."

Looking back on the paper 50 years after its publication, one researcher wrote that Kardashev's scale "was meant to represent a practical guideline for what could be expected in the course of SETI searches, not a profound theoretical insight into the nature of extraterrestrial intelligence."

And even as scientists interrogate Kardashev's ideas, the scale remains an important facet of SETI work, Ivanov said. "His name will stay."

Additional resources

- Read Kardashev's 1964 article on extraterrestrial signals.

- Read Ivanov's analysis and expansion of the Kardashev scale.

- Read another analysis of how Kardashev's scale aged.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.