Why haven't we found intelligent alien civilizations? There may be a 'universal limit to technological development’

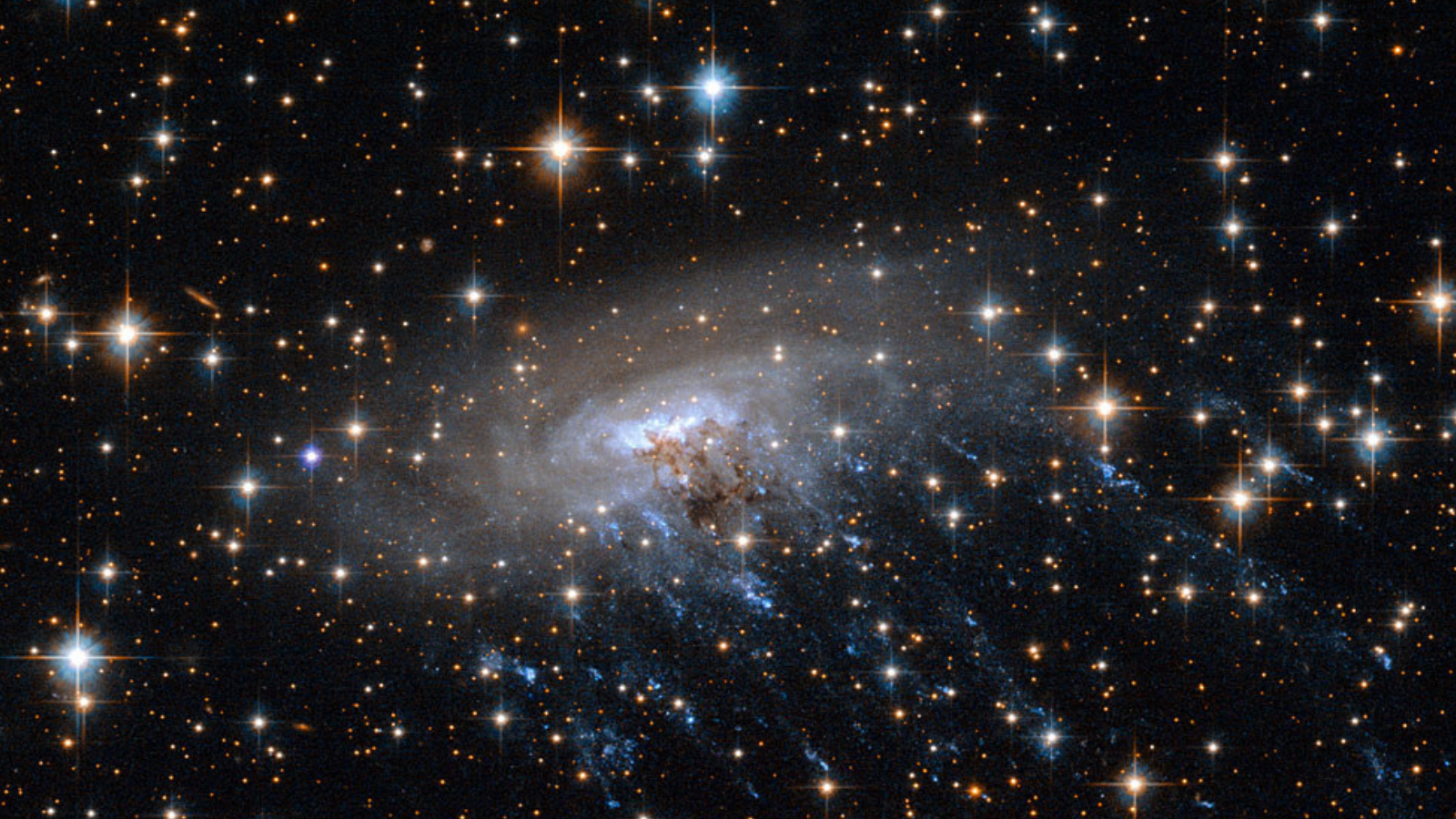

If the technological capacities of intelligent entities throughout the cosmos are unbounded, why haven't we seen signs of other intelligent life?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

In less than seven decades, humanity went from having no active flight technology to walking on the moon. It took only a little over a century to get from the first basic computer to a pocket-size device that enables widespread access to nearly the entire body of human knowledge within seconds. Based on that technological trajectory, there is a persistent assumption that our technological capacities are unbounded.

This notion, along with the discovery that habitable worlds are common throughout the cosmos, has influenced a question that has perplexed scientists and others for decades: "Why is the universe so quiet?" This conundrum, which is said to have been proposed by physicist Enrico Fermi in 1950, is known as the Fermi paradox. If our solar system is young compared with the rest of the universe and humans could be capable of interstellar travel someday, shouldn't we have seen signs that other intelligent entities have spread throughout the cosmos by now? Basically, where are the aliens?

Perhaps we haven't encountered alien civilizations because there's a "universal limit to technological development" (ULTD) for every intelligent species in the universe and this limit sits well below a civilization's ability to colonize an entire galaxy, Antonio Gelis-Filho, a researcher in public policy at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation at the School of Business Administration (FGV EAESP) in Brazil, proposed in a recent paper published in the journal Futures.

"If the ULTD hypothesis is correct, there has never been, there is not and there will never be something like an interstellar civilization, or anything similar to an 'interstellar conversation,'" Gelis-Filho told Space.com in an email.

Related: Are we alone? Intelligent aliens may be rare, new study suggests

Based on the history of the rise and fall of human civilizations, the feasibility of constructing and running scientific projects that expand our knowledge and technology, and the apparent lack of technological intelligence elsewhere in the cosmos, Gelis-Filho thinks we should be careful about assuming the technological capacities of humans and other intelligent beings are limitless.

The "uncrossable gap"

Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman once said, "What I cannot create, I do not understand." The most straightforward interpretation of this is that our technology — what we can create — is constrained by our knowledge.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There are, of course, natural limits to human technology. We can't travel in a straight line faster than the speed of light, for example. There may also be natural barriers to human knowledge — facts about the universe that are forever inaccessible to us due to the configuration of our biology. Sure, we have created technology that scaffolds our senses and cognition: Microscopes let us peer into the world of the small, telescopes provide a window into the world of the big, and computers crunch numbers and data that our individual minds are incapable of processing.

However, the technologies and experiments that allow us to expand our knowledge are coming at an ever-increasing price. Projects like the Large Hadron Collider at CERN ($4.75 billion to construct and $286 million annually), the International Space Station ($3 billion per year), and the international effort to achieve nuclear fusion at ITER (an estimated $18 billion to $20 billion for construction) show that human efforts to probe our scientific horizons require increasing energy and resources.

"If we are candid about it, the fact is that the last major fundamental advances in the science of the universe (macro- and micro-realms, cosmology and quantum mechanics) are almost a hundred years old," Gelis-Filho said.

Sure, black holes and other phenomena are much better understood today than they were a century ago, but their theory is nowhere as consequential to human technology as relativity and quantum mechanics have been, Gelis-Filho contends.

Just "compare the scientific evolution from 1830 (no theory of evolution, no theory of electromagnetism) to 1930 (relativity and quantum mechanics already there) and from 1930 to 2024 (still no unifying theory) for us to perceive that the rate of advancement is slowing, to say the least," Gelis-Filho said. "Low-hanging fruits have already been picked. The remaining ones seem to be hanging from impossibly high branches."

The growing price of probing the frontiers of human knowledge means we might decide the price is too high. Indeed, the European commission recently abandoned its plan to select a number of billion-euro flagship research projects, which included plans to convert solar and wind energy into fuels, and to bring cell and gene therapies into clinical settings. In such a case, the development of new technologies that leverage new breakthroughs in our understanding of reality will also come to a standstill, along with our dreams of becoming an interstellar civilization.

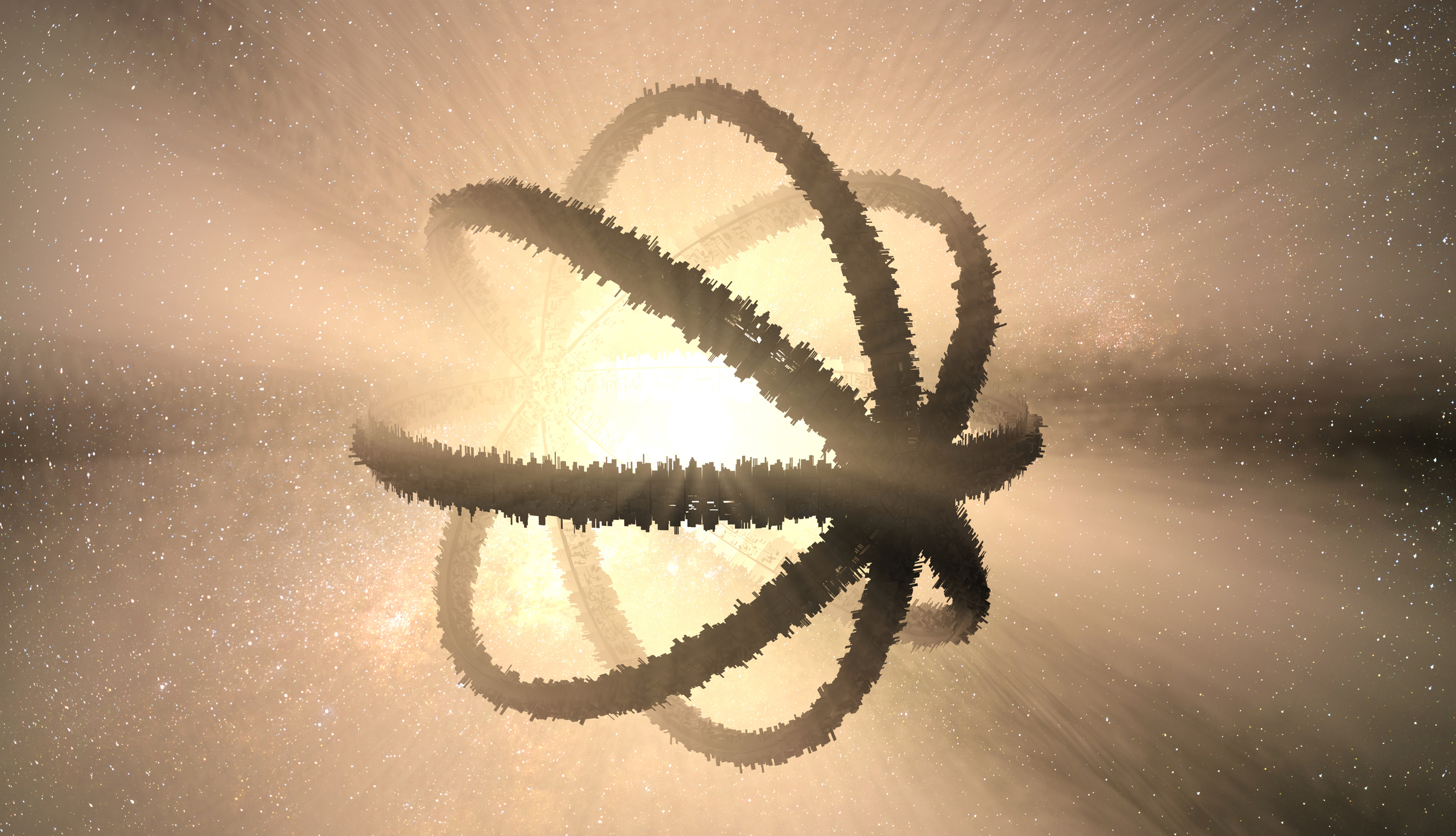

Any intelligent civilization in the cosmos will have to face this same scenario, Gelis-Filho said. At a certain point, no matter how ingenious they become, they will have to make a decision: Do we build a particle accelerator as large as the Milky Way to test our new unifying theory, for example, or do we build necessary infrastructure for our civilization's survival?

The ULTD hypothesis sustains that, even if a civilization decided to build such a machine to test the limits of their knowledge, they would discover that the levels of energy needed to perform experiments to facilitate a leap in scientific knowledge do not increase linearly. They would reach a point where their current technology would not allow them to cross the gap between one level and the next.

"Since the laws of physics are the same throughout the universe, every single civilization will eventually clash against that 'uncrossable gap,'" Giles-Filho said.

The cost of increasing societal complexity

Gelis-Filho also thinks lessons from the rise and fall of human civilizations can be applied to this astrobiological context. Complex societies expand by adding layers of societal complexity to produce more "energy" to keep growing. However, after a certain point, complexity does not "pay for itself," and its returns will decrease, he said.

"If we think of a hunter-gathering society, the number of social roles (chief, hunter, collector and so on) is minimal; in the Late Roman Empire, it was much higher and in our industrial society it is immensely higher," Gelis-Filho explained.

Of course, with added specialization, more complex societies can produce more. As people developed agriculture on Earth, for instance, the influx of food provided by the new technology led to new societal roles aimed at increasing production further. But as the level of complexity increased, so did the need for costly infrastructure to support it.

Related: First contact with aliens could end in colonization and genocide if we don't learn from history

Gelis-Filho borrows his argument from Joseph Tainter, an archaeologist who studied many complex societies throughout history. Tainter hypothesizes that, although the fatal blow to a society may vary (e.g., war, drought, epidemics or an astronomical event), the root cause is always the same: decreasing returns on complexity that have made the society fragile.

"I have applied the concept to any technological society anywhere in the universe," Gelis-Filho said. "Advanced spatial technology demands legacy infrastructure to be developed. That infrastructure is just a part of societal complexity. … It is possible that many non-terrestrial societies have collapsed because of diminishing returns on societal complexity, even before clashing against the limits imposed by energy requirements to test scientific theories."

Cosmic messages in a bottle

Despite all of this, Gelis-Filho doesn't rule out the possibility of receiving a message or signal from another intelligent civilization. The universal limit to technological development prohibits technological development beyond a level that prevents the organized, self-sustaining spread of a civilization beyond its solar system.

"However, it does not preclude the existence of 'castaway technology,' like wandering dead space probes (just think about the Voyager 1 in a hundred thousand years, silently crossing our galaxy), isolated messages being received (the Wow! signal being a candidate) or even 'alien dead Voyagers' being retrieved by us (however improbable that event is)," he said.

Such attempts to communicate with other intelligent civilizations across the vastness of space resemble "great cosmic bottle messages" — like a stranded captain of a sunken ship on a remote island trying to signal to the outside world with the rudimentary tools they have, Gelis-Filho explained.

Giles-Filho's hypothesis is one possible explanation for why our attempts to observe an interstellar civilization have fallen short. Yes, we have been searching for signs that we are not alone in the cosmos for only a few decades. Maybe we haven't been looking long enough, in the right place or even for the right thing. The unambiguous detection of an intelligent alien civilization would obviously prove the ULTD hypothesis wrong, as would the sudden leap in knowledge that could facilitate the expansion of human civilization into the stars. Until then, the ULTD hypothesis provides a sobering reminder that our species' destiny is not a given.

Conor Feehly is a New Zealand-based science writer. He has earned a master's in science communication from the University of Otago, Dunedin. His writing has appeared in Cosmos Magazine, Discover Magazine and ScienceAlert. His writing largely covers topics relating to neuroscience and psychology, although he also enjoys writing about a number of scientific subjects ranging from astrophysics to archaeology.