NASA will slam a spacecraft into an asteroid. This tiny witness will show us what happens.

Understanding the effects of the impact in detail is crucial for designing an effective planetary defense system.

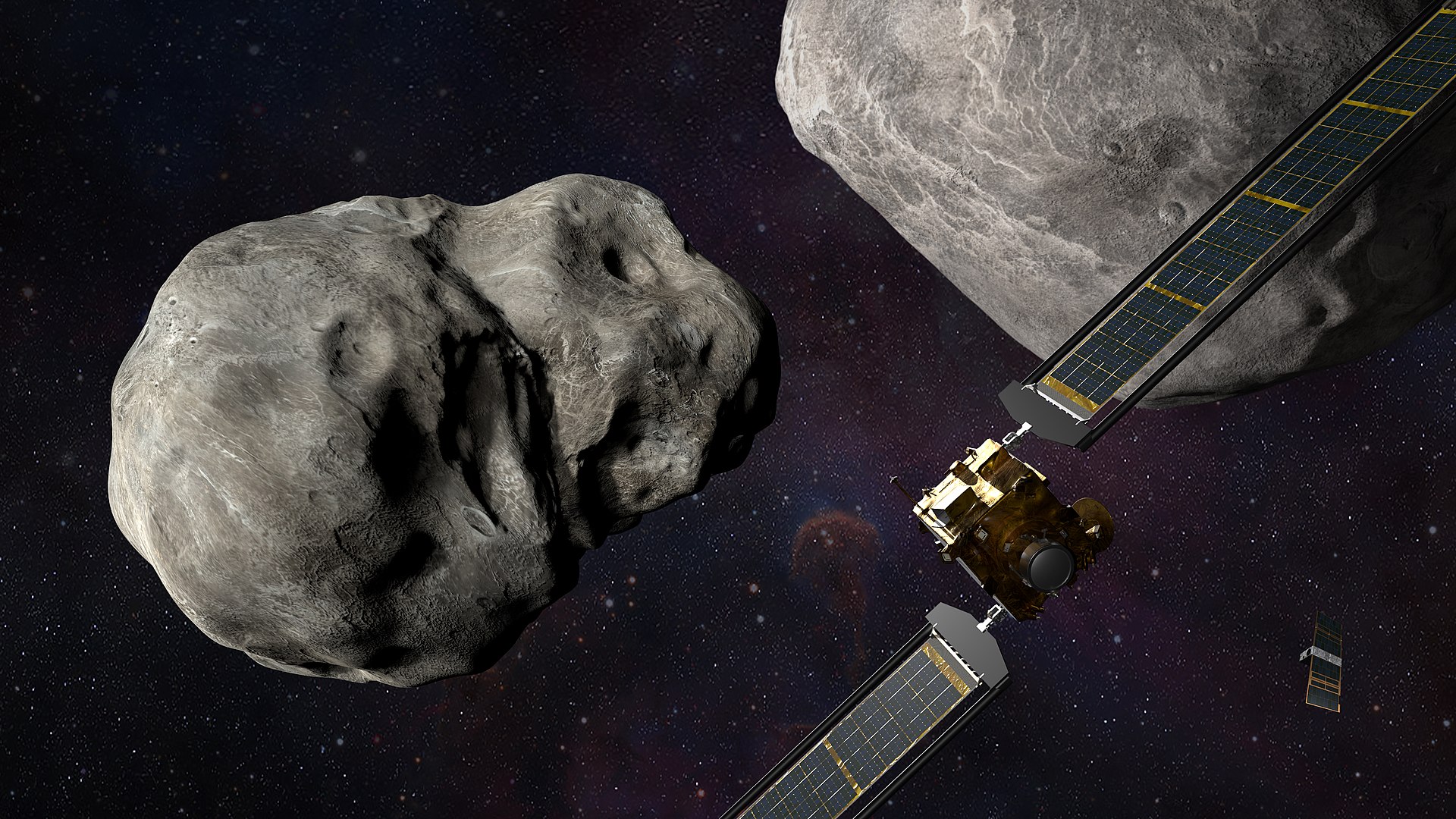

When NASA's DART spacecraft smashes into asteroid Dimorphos on Sept. 26, it will have a silent witness: An Italian cubesat called LICIACube will watch the ground-breaking experiment in real time for eager scientists on Earth.

LICIACube, or the Light Italian Cubesat for Imaging of Asteroids, is a 31-pound (14 kilograms) micro-satellite that has hitched a ride on DART (the Double Asteroid Redirection Test) to the Didymos-Dimorphos binary asteroid system. DART deployed the cubesat on Sunday (Sept. 11) at 7:14 p.m. EDT (2314 GMT) to give LICIACube 15 days to assume a safe position to observe DART's collision with Dimorphos. The impact is a first-of-its kind experiment designed to alter the orbit of a space rock in a crucial test of a planetary defense concept that may one day save the lives of millions of people on Earth.

"LICIACube will be released from the dispenser on one of DART's external panels, and will be guided (braking and rotating) to start its autonomous journey toward Dimorphos," Elena Mazzotta Epifani, an astronomer at Italy's National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) and a co-investigator on the LICIACube mission, told Space.com in an email. "The cubesat will point its cameras toward the asteroid system, but also to DART, and will probably take some pictures of it."

Related: NASA's DART asteroid-impact mission explained in pictures

The only first-hand witness

LICIACube, fitted with two optical cameras, will follow DART toward Dimorphos and eventually settle in to watch the drama from a safe distance of 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) as the 1,345-pound (610 kg) spacecraft hits the rock on Sept. 26, Mazzotta Epifani added. "The DART impact will be [seen] as an increase of the target luminosity by comparing images of Dimorphos taken before and after the impact," she wrote.

At the time of the impact, Dimorphos and Didymos will be about 6.8 million miles (11 million km) from Earth, according to NASA. Although Earth-based astronomers will not be able to see the impact, they will closely observe the system in the following weeks to determine whether the 12-hour orbit of the 560-foot-wide (170 meters) Dimorphos around the 2,600 foot-wide (800 m) Didymos will have sped up as expected. They will do that by measuring the intervals between the periods of brief dimming that take place when the two asteroids eclipse each other.

But although such observations might be enough to confirm that the experiment worked, they would not provide any detail of the effects of DART's impact on the asteroid. And so, right after DART smashes into Dimorphos, LICIACube will move closer to inspect the scene.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"LICIACube will … perform a 'fast fly-by' around 3 minutes after DART impact at a minimum distance of about 55 km [34 miles] from Dimorphos' surface at its closest approach," Mazzotta Epifani wrote. "The image acquisition by the two cameras onboard will be almost continuous for around 10 minutes and will be devoted to the target impact and non-impact sides, as well as to the plume produced by the DART impact."

LICIACube will then send the images to Earth, but Mazzotta Epifani warned it might take weeks to get down all the data.

We know nothing about Dimorphos

Understanding the effects of DART's impact on Dimorphos in depth is crucial as a similar system might one day be needed to deflect a rock on a collision course with Earth. An asteroid the size of Dimorphos could cause a continent-wide destruction while the impact of one the size of the larger Didymos could be felt worldwide.

But there's a catch: Although astronomers know in great detail orbits of most of the 26,115 currently known near-Earth asteroids (2,000 of which are classified as "potentially hazardous" due to their size and closest approach to Earth), they know surprisingly little about these rocks. In particular, scientists don't understand the density of the material the rocks are made of and can only guess how the surface might behave upon impact.

The team behind NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission, which touched down on the near-Earth asteroid Bennu in October 2020, experienced firsthand the pitfalls of these unknowns. The asteroid's unexpectedly soft surface nearly swallowed up the spacecraft, the touchdown generating what OSIRIS-REx principal investigator Dante Lauretta described as "a huge wall of debris" that could easily have destroyed the spacecraft.

Lauretta, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, told Space.com when the incident was announced it suggested a deflection attempt might be more difficult than thought, since soft-surfaced asteroids could just absorb the impact.

The team behind DART knows just as little about Dimorphos as the OSIRIS-REx team knew about Bennu before the spacecraft arrived at the asteroid. The images captured by DART itself before the impact and subsequently by LICIACube, will be the first detailed views of Dimorphos astronomers will ever see.

"We know general surface properties of the larger Didymos, thanks to ground-based spectroscopic and photometric measurements, but we do not know almost anything about Dimorphos, which is too small to produce an effect disentangled from the one coming from the main body," Mazzotta Epifani wrote. "We *presume* from theoretical models on formation of binary asteroids that Dimorphos is very similar to Didymos, but we know virtually nothing about the degree of cohesion of surface materials, the size distribution of the surface debris, and so on."

Scientists think Dimorphos is a so-called "rubble pile asteroid" like Bennu: a conglomeration of boulders and dirt that broke off in the past from the main asteroid Didymos and is now only held together by the force of gravity. Since the asteroid is rather small, this force is quite feeble. For this reason, astronomers don't understand the impact that DART will have, how much matter it will throw up into space and how big a crater it might leave behind.

Lessons for the future

"Together, DART and LICIACube will analyze for the first time and with high detail the physical properties of a binary near-Earth asteroid, allowing us to investigate its nature and have hints on its formation and evolution," Mazzotta Epifani wrote. "LICIACube will obtain multiple images of the ejecta plume produced by the impact itself, of the DART impact [crater] size, as well as the non-impact hemisphere to help us to study the size and morphology of the crater and the effects on the surface properties in the surroundings."

The good news is that the more information scientists gather, the better they will be able to predict effects of possible future interventions on similar asteroids.

The Italian Space Agency, which oversees the LICIACube mission currently evaluates plans to extend the mission to conduct other studies of the Didymos-Dimorphos binary asteroid system, Mazzotta Epifani wrote, adding that any decisions on prolonging the mission beyond the immediate aftermath of the impact will only be made after Sept. 26.

Italy's first deep space mission

For the Italians, who have a burgeoning space industry that has contributed to some of the most high-profile European space projects (including the European Columbus module of the International Space Station), LICIACube is the first deep-space mission the country will operate on its own. Developed and built in less than three and a half years, LICIACube is similar to ArgoMoon, one of the cubesats hitching a ride to the moon on NASA's Artemis 1 mission, which is still waiting for lift off after a fuel leak stopped a launch attempt on Sept. 3.

"LICIACube is not only the first mission in deep space that Italy will operate, it is also the first fully designed, realized and managed in Italy, including data reception and management," Mazzotta Epifani wrote.

With LICIACube, Italy stepped in to fill the gap created by budget approval delays in the European Space Agency's (ESA) HERA mission, a much larger spacecraft, which was originally intended to arrive at the Didymos-Dimorphos duo before the DART impact to inspect the system and then observe the crash and study its aftermath in detail. ESA still plans to launch HERA, but the spacecraft will not reach Didymos before 2027.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.