Missing microbial poop in Venus' clouds suggests the planet has no life

"If life was responsible for the sulfur dioxide levels we see on Venus, it would also break everything we know about Venus's atmospheric chemistry."

Venus' atmosphere bears no signs of microbes eating or pooping, suggesting that the odd chemical composition of the planet's clouds cannot be explained by extraterrestrial life.

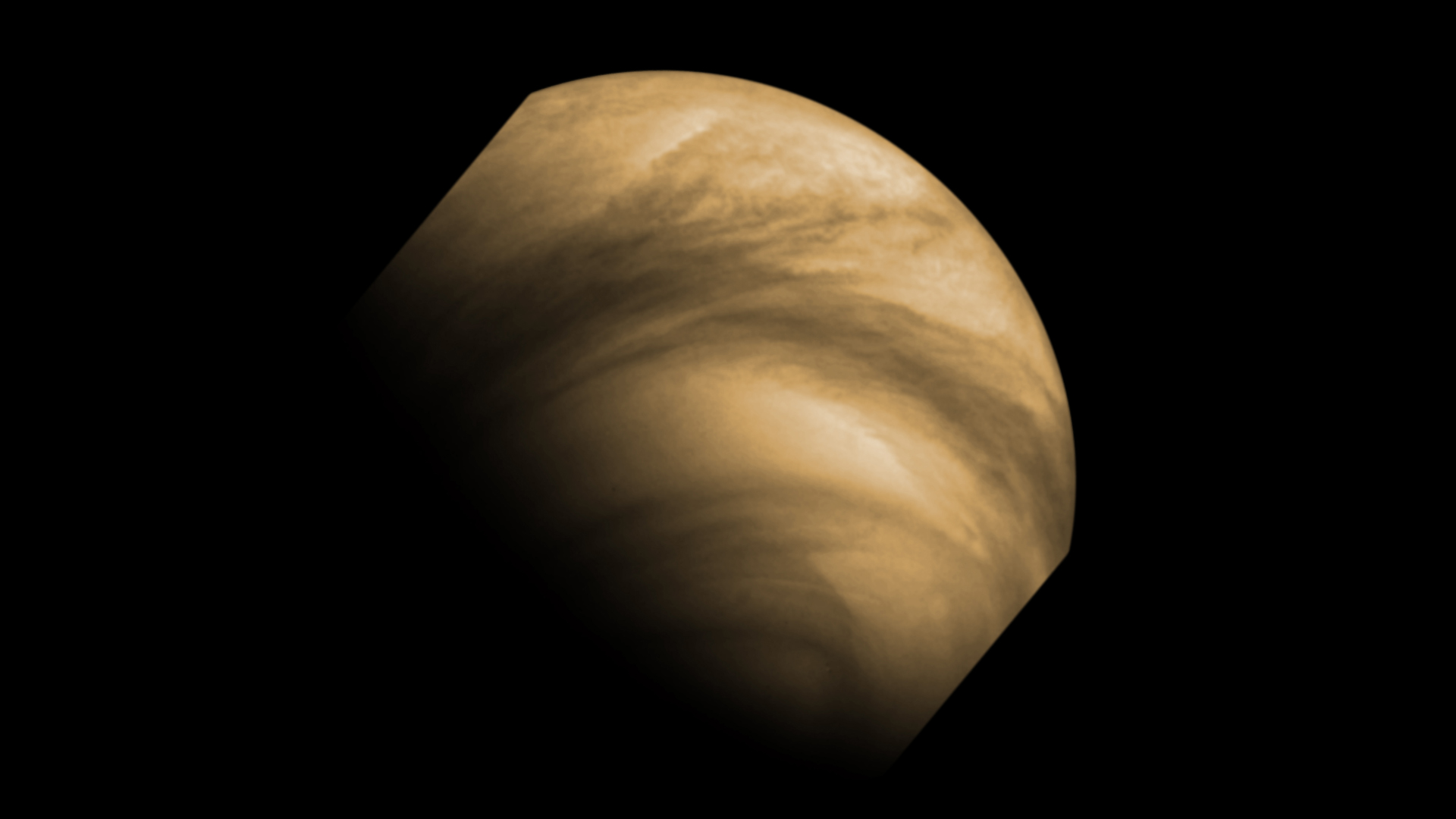

In a new study, researchers analyzed the biochemistry of the thick, sulfur-rich Venusian clouds, which have fascinated scientists for decades. They looked for "fingerprints" that any potential cloud-dwelling organisms would leave there as a result of their feeding and excretion.

"We've spent the past two years trying to explain the weird sulfur chemistry we see in the clouds of Venus," Paul Rimmer, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Cambridge in the U.K. and a co-author of the study, said in a statement. "Life is pretty good at weird chemistry, so we've been studying whether there's a way to make life a potential explanation for what we see."

Related: Life on Venus may never have been possible

The researchers modeled chemical reactions expected in Venus' atmosphere, which is rich in sulfur dioxide. Concentrations of sulfur dioxide are high in the clouds closer to the planet's surface but diminish with altitude. Scientists thought the sulfur dioxide might be disappearing as it got eaten by cloud-dwelling critters. When the researchers ran the models, however, they found that chemically, that hypothesis didn't work.

"If life was responsible for the sulfur dioxide levels we see on Venus, it would also break everything we know about Venus's atmospheric chemistry," Sean Jordan, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge and first author of the paper, said in the statement. "We wanted life to be a potential explanation, but when we ran the models, it wasn't a viable solution."

The models simulated metabolic reactions that the atmospheric microbes would use to produce energy from food sources and generate waste. The results suggested that although such microbes could suck out some sulfur dioxide from the clouds, that process would produce large molecules that have not been detected.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We looked at the sulfur-based 'food' available in the Venusian atmosphere — it's not anything you or I would want to eat, but it is the main available energy source," Jordan said. "If that food is being consumed by life, we should see evidence of that through specific chemicals being lost and gained in the atmosphere."

The researchers said that although the study failed to produce the results they had hoped for, it provides valuable insight into the atmospheric chemistry of alien planets, and the methodology developed for this study could be used to look for life outside the solar system.

"Even if 'our' Venus is dead, it's possible that Venus-like planets in other systems could host life," said Rimmer. "We can take what we've learned here and apply it to exoplanetary systems — this is just the beginning."

In particular, the researchers said, the results might guide the observations of the James Webb Space Telescope, which is set to reveal its first scientific images next month, as the telescope is capable of detecting such chemical fingerprints in the atmospheres of distant exoplanets.

Now that life doesn't seem to be the answer to Venus' odd atmospheric chemistry, scientists still have a lot of work to do to explain what's actually going on in those thick, sulfur-rich clouds.

The study was published June 14 in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.