NASA has a life-detecting instrument ready to fly to Europa or Enceladus

A new device containing eight instruments designed to search for life in water could fly on a future mission to Enceladus or Europa.

NASA scientists have developed a new device designed to autonomously detect life in the watery plumes shooting into space from icy moons like Enceladus and perhaps Europa.

Saturn's moon Enceladus and Jupiter's moon Europa have long intrigued scientists as prime locations in the solar system where life could exist. Both have hidden oceans of liquid water with potentially habitable conditions beneath their icy veneer, but directly reaching those oceans through the thick ice will be difficult.

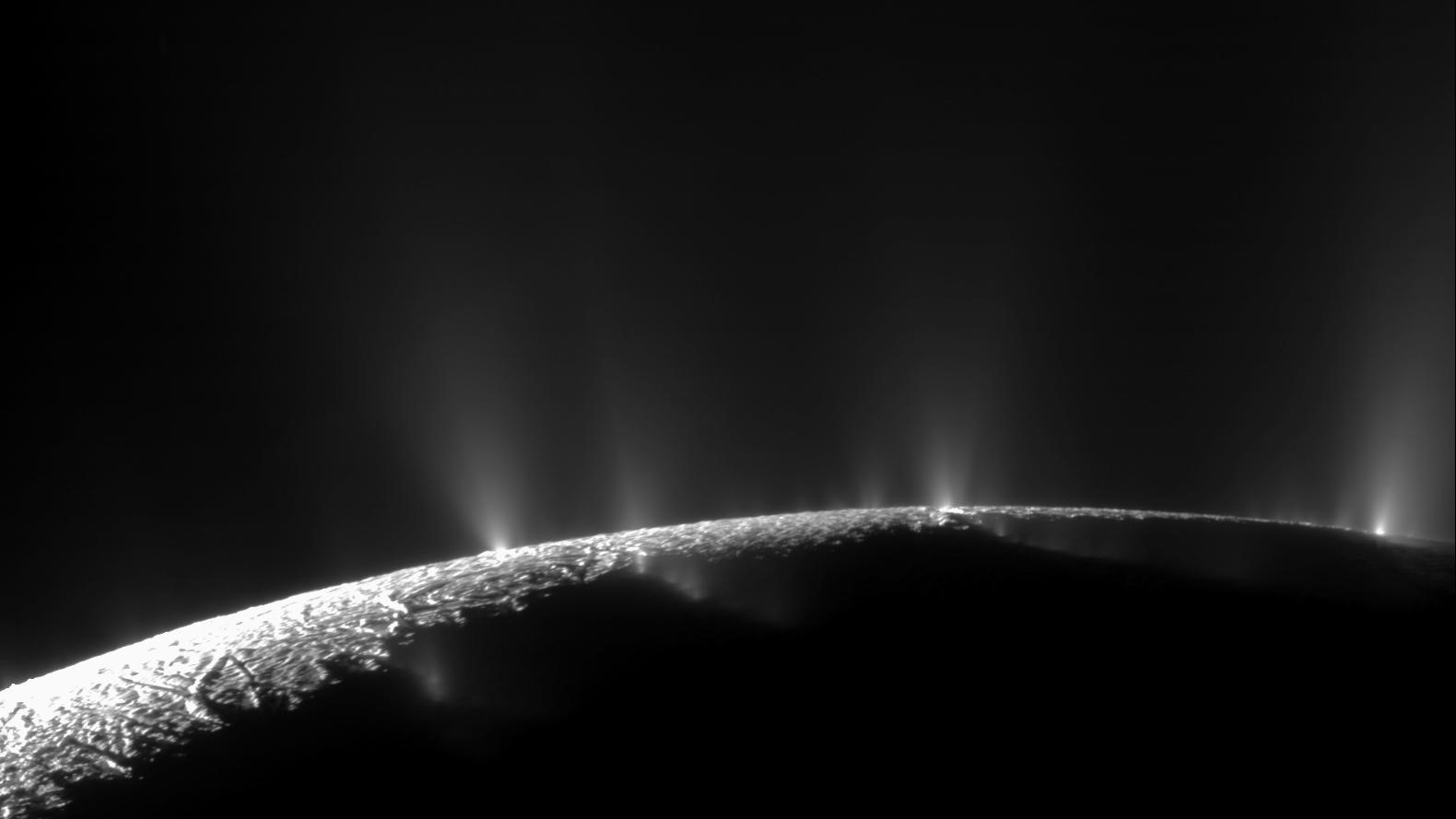

Fortunately, the moons can bring their oceans to spacecraft. In 2006, the Cassini mission to Saturn discovered plumes of water vapor spewing from Enceladus, which is 310 miles (500 kilometers) wide. Similarly, the Hubble Space Telescope has found intriguing evidence for plumes emanating from Europa, which is much larger at 1,940 miles (3,120 km across). Now, a spacecraft equipped with NASA's new Ocean Worlds Life Surveyor (OWLS) device could collect samples of water while flying through the plumes, then search for any microorganisms that the geysers may have spurted up into space.

Related: Behold! Our closest view of Jupiter's ocean moon Europa in 22 years

Cassini actually flew through the plumes, but neither it nor any other mission to the outer solar system to date has been equipped with instruments that can find life. Any future mission carrying OWLS would be different.

However, because of the great distances separating Earth from Jupiter and Saturn, bandwidth for transmitting data back is low. Therefore, OWLS must collect huge tranches of data, autonomously analyze it to hopefully discover life by itself, and then send just the relevant results back to Earth.

"We're starting to ask questions now that necessitate more sophisticated instruments," Lukas Mandrake, who is the OWLS' instrument autonomy system engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California, said in a statement. "Are some of these other planets habitable? Is there defensible scientific evidence for life rather than a hint that it might be there? That requires instruments that take a lot of data, and that's what OWLS and its science autonomy is set up to accomplish."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

OWLS isn't just one smart instrument, but a suite of eight experiments capable of investigating whether life exists in the samples that it collects. Tests conducted with OWLS in California's extremely salty Mono Lake, which scientists think may not be too dissimilar to the salty waters of Europa and Enceladus' oceans, successfully "discovered" life in the Californian lake. Now, with a bit of downsizing, OWLS is ready to take on the icy moons, its developers say.

"We have demonstrated the first generation of the OWLS suite," Peter Willis, who is OWLS' co-principal investigator and science lead from JPL, said in the statement. "The next step is to customize and miniaturize it for specific mission scenarios."

Among the eight instruments within OWLS is the Extant Life Volumetric Imaging System (ELVIS), which is a group of various microscopes, developed in association with scientists at Portland State University in Oregon. Most excitingly, among ELVIS' microscope arsenal is a Digital Holographic Microscope (DHM). It is able to record video of water samples at a microscopic scale for tens of seconds, and then, as the name implies, convert the video into three-dimensional, holographic imagery. Machine-learning algorithms then get to work analyzing the holographic video of the sample: Ordinary particles in the water will simply drift lazily or remain motionless, but more erratic motion will betray any living microorganisms present.

The DHM can work in conjunction with OWLS' Organic Capillary Electrophoresis Analysis System (OCEANS). Capillary electrophoresis is a technique for separating organic molecules — such as the various amino acids, fatty acids and nucleic acids life relies on — in a liquid using electric fields. The molecules are then sent to a mass spectrometer, which measures the masses of particles in the sample, and a volume fluorescence imager, which uses dyes to bind these chemical building blocks together. When excited by a laser, the compounds fluoresce, or glow, giving a target for the DHM to focus on.

OWLS' development has come too late for inclusion on the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), which blasts off in 2023, or NASA's Europa Clipper mission, which launches in 2024.

However, several missions have been proposed to return to Saturn's Enceladus in the future. Scientists at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory have submitted to NASA a mission concept called Orbilander, which would operate as both an orbiter and a lander on Enceladus. Then there's Breakthrough Initiatives' putative privately funded Enceladus mission. A concept previously turned down by NASA, called the Enceladus Life Finder, could also be revived at some point.

Enceladus is too tempting a target to ignore for long, and when we return, OWLS is ready to go along for the ride.

Follow Keith Cooper on Twitter @21stCenturySETI. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.