The loss of dark skies is so painful, astronomers coined a new term for it

'Noctalgia' is a feature of the modern age.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Humanity is slowly losing access to the night sky, and astronomers have invented a new term to describe the pain associated with this loss: "noctalgia," meaning "night grief."

Along with our propensity for polluting air and water and the massive amounts of carbon we're dumping into the atmosphere to trigger climate change, we have created another kind of pollution: light pollution.

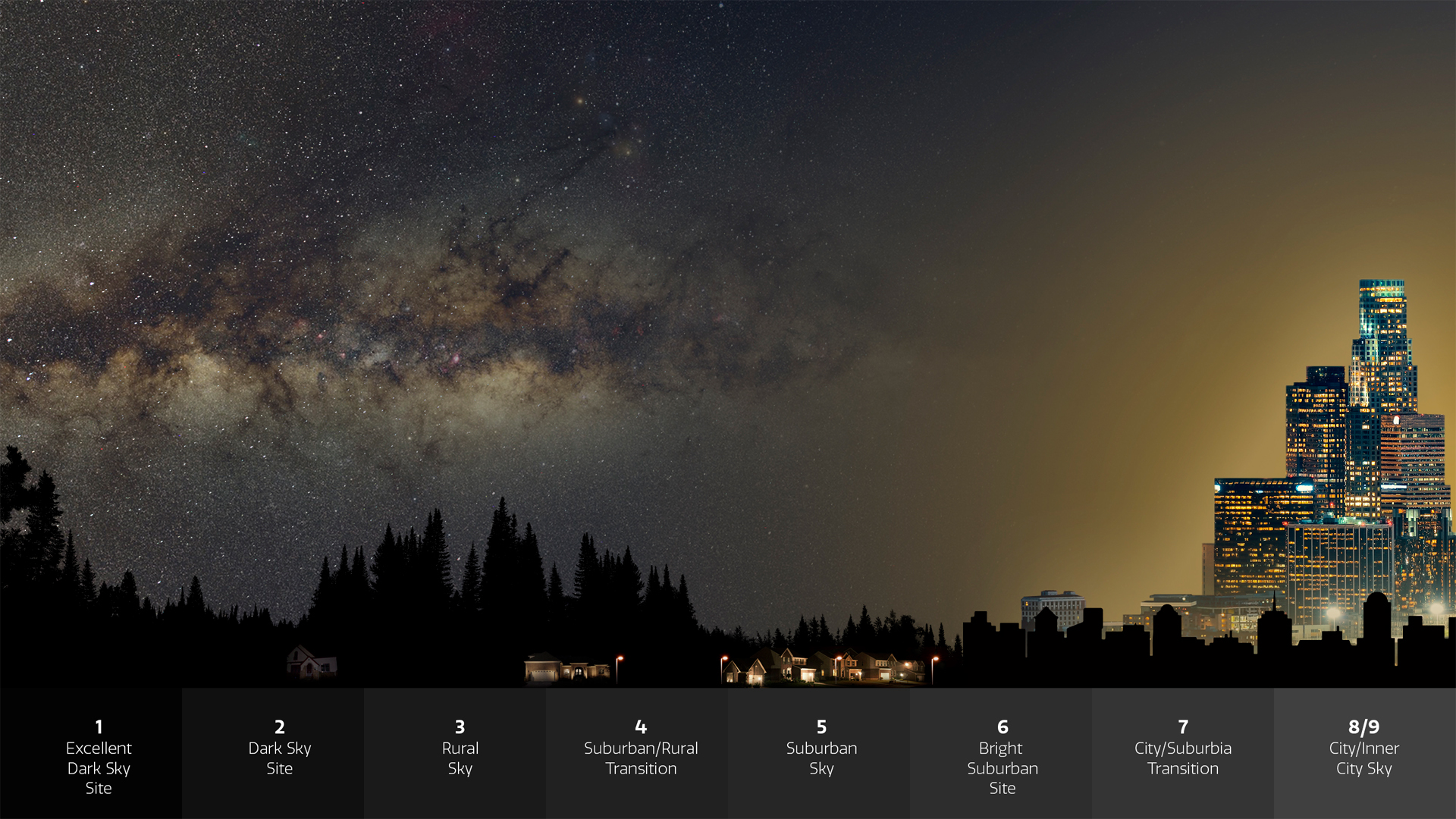

Most of our light pollution comes from sources on the ground. While humans have had campfires and handheld lanterns for ages, the amount of light we produce through electricity is astounding. We light up our office buildings, streets, parking lots and homes. Of course, some of this lighting is needed for safety and security, but much of it goes to waste. Plus, until we became more aware of light pollution, we tended to allow lighting to spill in every direction, both toward the areas we were trying to illuminate and straight up into the night sky.

Related: Light pollution is damaging views of space for the majority of large observatories, survey finds

Ironically, switching to efficient LED lighting often exacerbates the problem. Because those kinds of lights are so inexpensive to operate and last so long, many city and building planners just assume the lights can be left on all night, without any consideration of the cost or replacement.

Only in the most remote deserts, wilderness areas and oceans can you find a sky as dark as our ancestors knew them.

More recently, the explosive growth in satellite communication "constellations," like SpaceX's Starlink system, has put orders of magnitude more satellites into orbit than even a decade ago, with even more on the way. Those satellites don't just spoil deep-space astronomical observations when they cross a telescope's field of view; they also scatter and reflect sunlight from their solar arrays. The abundance of satellites is causing the overall brightness of the sky to increase all around the globe. Some researchers have estimated that, on average, our darkest night skies, located in the most remote regions of the world, are 10% brighter than they were a half century ago, and the problem is only getting worse.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The loss of the night sky has several tangible and cultural impacts. We are losing a rich tradition of human cultural knowledge; cultures around the world and throughout history have used the sky as a springboard for the imagination, painting heroes, monsters and myths in the constellations. Nowadays, city dwellers are lucky to see even the brightest stars in the sky, let alone the faintest sketch of a familiar constellation.

Related: The constellations of the western zodiac

These millennia-old sky traditions aren't just random stories meant to entertain around the fire; they are often cornerstones of entire cultures and societies. We all share the same sky, and anyone from the same culture can identify the same constellations night after night. The loss of that access and heritage is a loss of part of our humanity.

Many animal species are suffering as well. What good are night-adapted senses in nocturnal species if the night sky isn't much darker than the daytime sky? Researchers have identified several species whose circadian rhythms are getting thrown off, making them vulnerable to predation (or, the reverse: the inability to effectively locate prey).

Given the harmful effects of light pollution, Aparna Venkatesan, a cosmologist at the University of San Francisco, and John Barentine, astronomer and science communicator at Dark Sky Consulting, have coined a new term to help focus efforts to combat it. Their term, as reported in a brief paper in the preprint database arXiv and in an e-Letter comment (which is not peer reviewed) to the journal Science, is "noctalgia." In general, it means "sky grief," and it captures the collective pain we are experiencing as we continue to lose access to the night sky.

Thankfully, there is a way to tackle noctalgia, just as there are ways to combat climate change. On the ground, efforts have sprung up across the globe to create dark-sky reserves, where surrounding communities pledge not to encroach with further expansions of light pollution. Still, those are usually in extremely remote and inaccessible regions of the globe, so other efforts have focused on working with community and business leaders to install night-friendly lighting, such as devices that turn off automatically or point only at the ground (or are simply not used at all).

Tackling satellite-based pollution is another matter, as that will require international cooperation and pressure on companies like SpaceX to be better stewards of the skies they are filling with equipment. Still, it's not impossible, and hopefully someday, noctalgia will be a thing of the past.

Update 11/10: The term "noctalgia" was reported in an e-Letter comment to the journal Science, not in a letter; e-letters are not peer-reviewed.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.