Gravitational-wave treasure trove reveals dozens of black hole crashes

Scientists can now catch gravitational waves better than ever before.

Although physicists only observed the first of these cosmic "chirps" in 2015, subsequent improvements in the detectors have opened up more and more of these signals to scientific study. The twin Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detectors in Louisiana and Washington, plus a European counterpart called Virgo, are currently on another observing hiatus for the coronavirus pandemic and ongoing upgrades, but scientists affiliated with the project have spent their time combing through data to create a new catalog of dozens of gravitational-wave signals detected during the first half of the third joint observing campaign, which ran from April to September 2019.

"One key to finding a new gravitational-wave signal about once every five days over six months were the upgrades and improvements of the two LIGO detectors and the Virgo detector," Karsten Danzmann, director at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Germany, said in a statement.

In images: The amazing discovery of a neutron-star crash, gravitational waves & more

In particular, he pointed to new hardware like lasers and mirrors, plus new techniques for reducing background noise. "This increased the volume in which our detectors could pick up the signal from, say, merging neutron stars by a factor of four!" Danzmann said.

The better sensitivity has allowed scientists to capture more gravitational waves, but also a more diverse array of signals, according to researchers affiliated with the project.

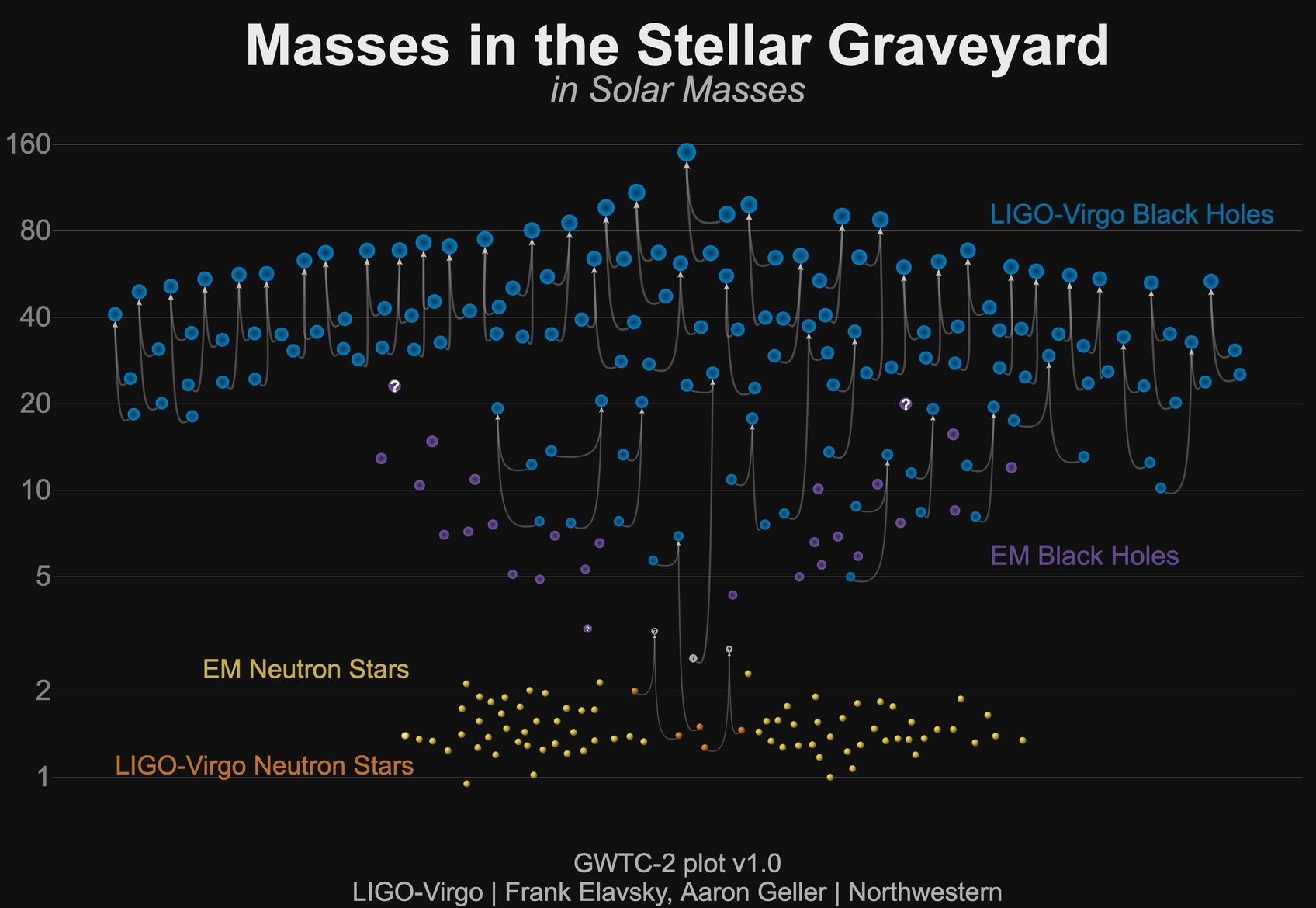

"When you look at the catalog, there's one thing all events have in common: They come from mergers of compact objects such as black holes or neutron stars. But if you look more closely, they all are quite different," Frank Ohme, a physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Germany, said in the statement. "We're getting a richer picture of the population of gravitational-wave sources. The masses of these objects span a very wide mass range from about that of our sun to more than 90 times that, some of them are closer to Earth, some of them are very far away."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A handful of the 39 detections included in the new release have already hit headlines, including the first observed lopsided black-hole merger, the first observed merger to create an intermediate-mass black hole, and the first observed merger to include a mysterious object that falls in the size range between neutron stars and black holes.

But those aren't the only intriguing detections in the batch, the researchers emphasized. One of the detections might represent a small black hole and a neutron star, a mixed merger that physicists have been waiting to see. "Unfortunately the signal is rather faint, so we cannot be entirely sure," Serguei Ossokine, another physicist at the institute said in the release.

Another detection represents the lightest black holes scientists have observed merging to date, he added — one about six times the mass of the sun and the other half again as large.

And there's still more data to be studied. The second half of the same observing run began in November 2019 and lasted until the coronavirus pandemic forced the detectors to send scientific staff home for safety in late March 2020.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.