'Improved' Gravitational-Wave Detectors Rake in Five Exciting Finds in a Month

And the observation round has just begun.

Just a month into a new observing round after significant improvements, gravitational-wave detectors have already used ripples in space-time to pinpoint five potential collisions of cosmic proportions — including one that might be the first-ever black hole found merging with a neutron star.

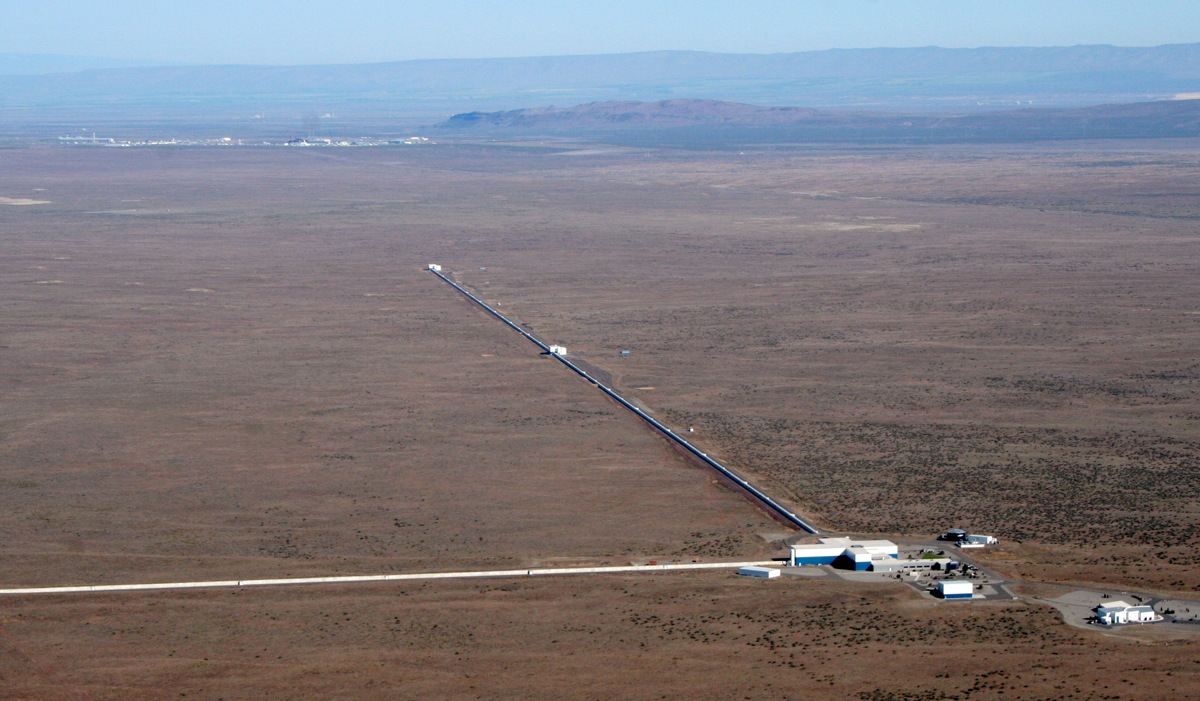

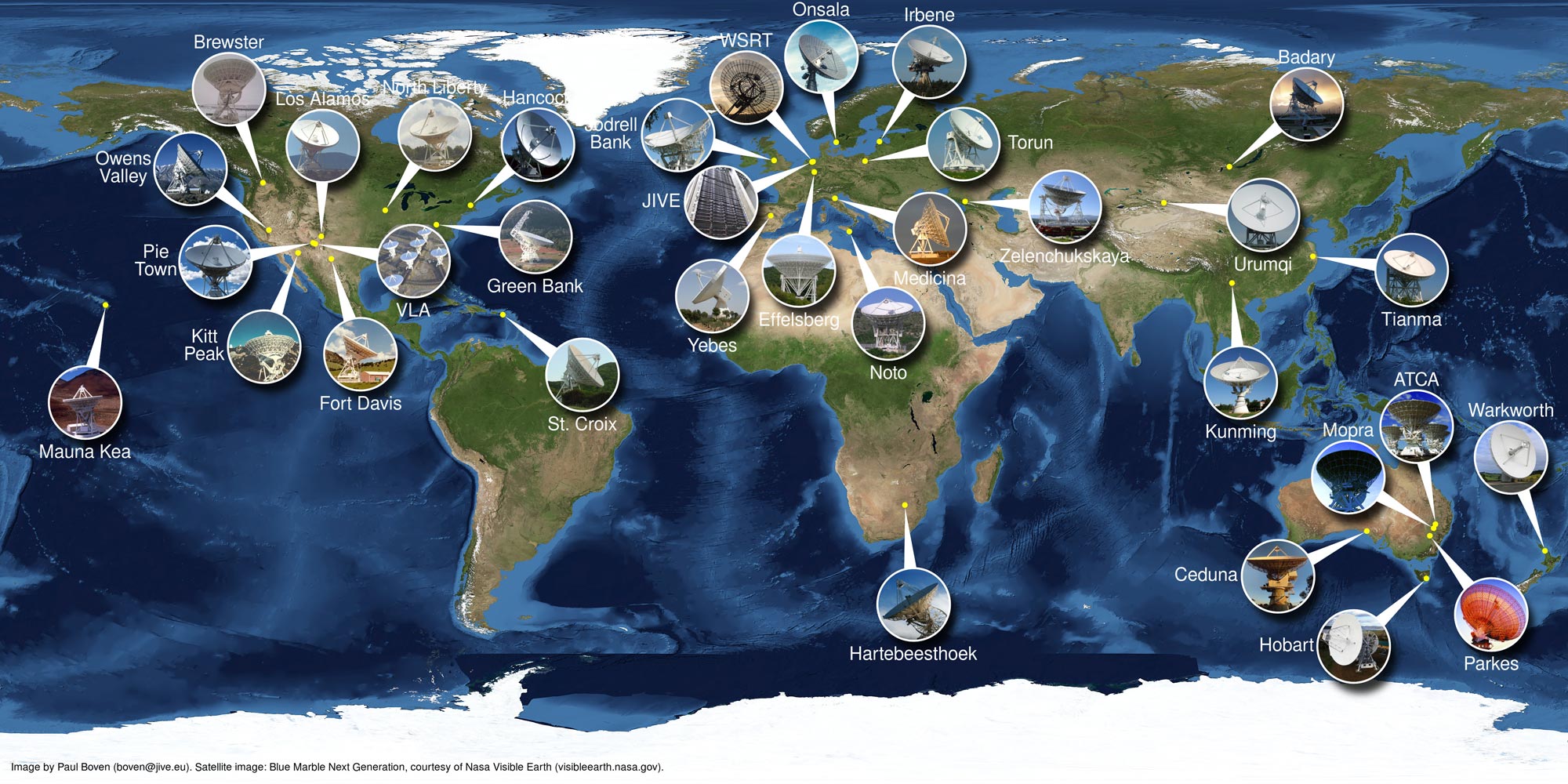

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) started its third observation round in April, using its two detector locations — one in Washington state and one in Louisiana — combined with the Virgo detector in Italy to pinpoint titanic clashes across the cosmos.

During a news conference this morning (May 2), LIGO and Virgo researchers discussed the collaboration's most recent findings and what the future holds for the rapidly improving field of gravitational-wave astronomy.

Related: LIGO Is Up and Running Again and Already Spotted Two Possible Black Hole Mergers

"This run opens a new era in gravitational-wave astronomy, one in which detection candidates are being publicly released as quickly as possible after we take the data. In just one month of observing, we've identified five gravitational-wave candidates, and this has been made possible by the substantial improvements to the LIGO and Virgo detectors over the past 18 months," Patrick Brady, an elected LIGO spokesperson and physicist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, said during the news conference.

By tracking minuscule distortions in space-time — based on tiny variations in how quickly lasers are able to traverse parts of a giant L-shaped structure — each of the LIGO detectors is able to sense massive collisions millions or billions of light-years from Earth. By combining their measurements from across the U.S., and adding detections from the similar Virgo detector in Italy, scientists can triangulate potential sources of the cataclysmic events. And as these tools are calibrated to be more sensitive over time, they can pick up fainter and more distant signals.

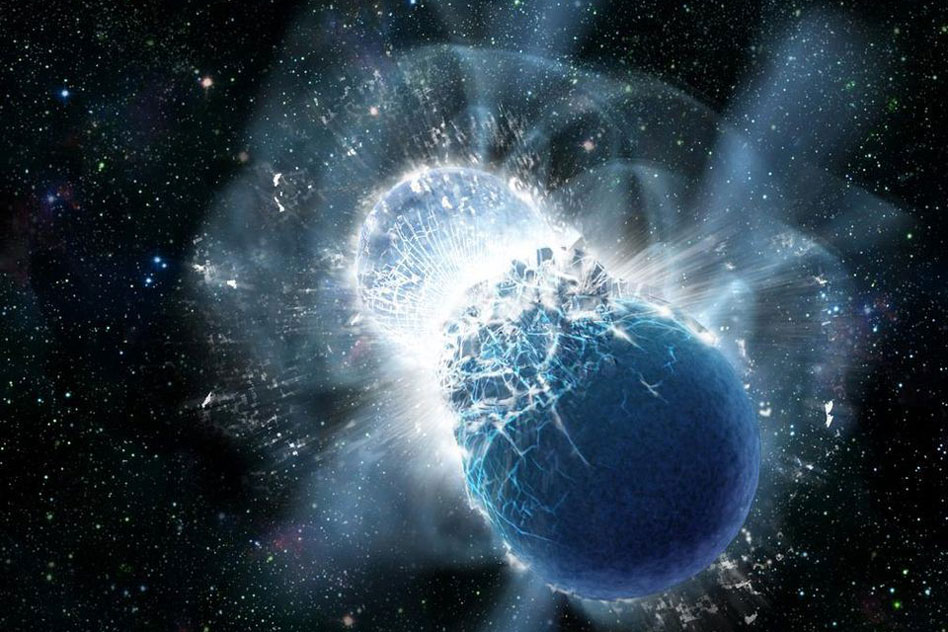

Three of the newest results appear to be mergers involving two black holes, and one seems to be a merger of two superdense neutron stars, Brady said. And "the fifth candidate, which we found on the 26th of April, allows the intriguing possibility that it came from the collision of a neutron star with a black hole," he added. "Unfortunately, that candidate is rather weak, so it's going to take us some time to reach a robust conclusion about it. Astronomers around the world have been excitingly following up the candidates from last week using telescopes on the ground and in space, though it seems at the moment neither of the sources have been pinpointed, but this is truly a global and multidisciplinary endeavor."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Indeed, April has been an incomparable scientific month," added Giovanni Prodi, Virgo's data analysis coordinator and a researcher at the Università di Trento and INFN Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare.

Since its first detection in 2015, LIGO has recorded evidence for two neutron-star mergers, 13 black hole mergers and one possible merger of a black hole and a neutron star, according to a statement released by MIT. Neutron-star mergers can produce light, which sends telescopes racing to find visible evidence of the events. (Researchers were able to spot light from the first neutron-star merger, detected in 2017, using more than 70 ground- and space-based telescopes.)

Astronomers are still searching for evidence of the two most recent detections, on April 25 and 26. The first, a potential neutron-star merger, likely occurred about 500 million light-years from Earth, researchers said in the statement. But because only one of the two LIGO observatories picked up the signal, along with Virgo, researchers have to search more than a quarter of the sky for evidence of the collision.

The second, which may have been a neutron star colliding with a black hole, happened roughly 1.2 billion light-years away; it was detected at all three sites, letting scientists narrow down its location to about 3 percent of the sky.

While LIGO doesn't coordinate astronomers searching for the targets they find, the project ise encouraging that search by releasing preliminary results quickly after each detection, researchers said during the news conference.

Related: First Glimpse of Colliding Neutron Stars Yields Stunning Pics

"Also unique to this observing run, we're now using an automated public alert system for the first time, so you can now follow along with LIGO/Virgo events on Twitter as the action is happening," Jess McIver, a researcher at Caltech's LIGO laboratory, said during the news conference.

"And these public alerts also give a deeper glimpse into the scientific process," McIver added. "Anyone can follow how our understanding of these events is evolving through careful analysis of the data and improved calibration, so we expect there will be much more insight into the laws of nature and the composition of the universe to come from this observing round and beyond."

These first notifications go out very soon after detections, but researchers at the gravitational- wave detectors continue to analyze the signals to filter out background noise and pin down how likely it is to be certain kinds of signals after the fact, posting updated bulletins. The researchers may publish papers on exceptionally interesting candidates within about three months, Brady said, and ideally the collaboration will release a final list after about six months detailing the candidates and confirmed events for each portion of the run.

The researchers added that they only expect more and better results from the remainder of the round — and that a new detector, the Kamioka Gravitational Wave Detector (KAGRA) in Japan, should be online to help by the final parts of the observing run. And they only anticipate greater sensitivity in observing rounds to follow. (Plus, a planned LIGO facility in India would further boost discoveries.)

"The most exciting thing of the beginning of O3 [this third observation round] is that it's clear we are going from one event every few months to a few events every month," Salvatore Vitale, a researcher at the LIGO Laboratory at MIT, said during the news conference. "This is going to allow for all these kinds of tests that require either a very loud, very clear detection or a lot of detections. And we will have both of them."

The researchers said that, in the future, gravitational-wave detectors might be able to record distant supernovas — right now, in our galaxy, but someday perhaps in farther galaxies. They may also be able to detect signals from spinning neutron stars or other exotic sources. And they could learn more about the fates of the mergers, such as if neutron-star mergers form a new, bigger neutron star, or become unstable and sink into a black hole.

"The great thing about where we are right now is we're just beginning to see the field of gravitational-wave astronomy open," Brady said. "As the detectors go through a sequence of improvements over the next decade, we're going to have the capability of seeing [black hole and neutron-star mergers] throughout the universe and ... the possibility to perhaps measure gravitational waves from spinning neutron stars and even things we haven't yet thought of as serious sources."

"And that's a big thing for us; opening a new window on the universe like this really, hopefully brings us a whole new perspective on what's out there," he added.

- Epic Gravitational Wave Detection: How Scientists Did It

- 'New Era' of Astrophysics: Why Gravitational Waves Are So Important

- Hunting Gravitational Waves: The LIGO Laser Interferometer Project in Photos

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.