Don't miss the longest partial lunar eclipse of the century next week

The partial eclipse takes place next week on the morning of Nov. 19

The longest partial lunar eclipse of the century is due to take place next week between Nov. 18 and. 19, and the gorgeous phenomenon will be visible in all 50 U.S. states.

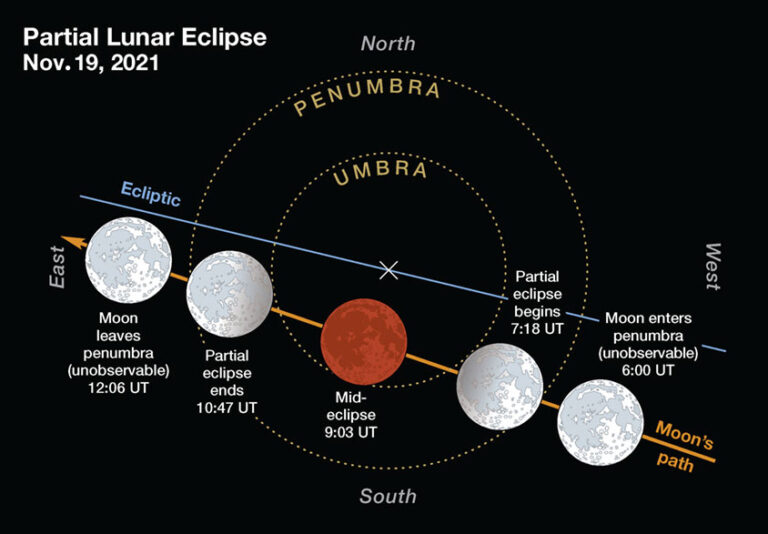

NASA forecasts that the almost-total eclipse of the Micro Beaver Full Moon will last around 3 hours, 28 minutes and 23 seconds — beginning at approximately 2:19 a.m. EST (7:19 a.m. UTC); reaching its maximum around 4 a.m. EST (9 a.m. UTC); and ending at 5:47 a.m. EST (10:47 a.m. UTC). The Micro Beaver moon is so named because it occurs when the moon is at the farthest point from Earth and in the lead-up to beaver-trapping season.

Related: Beaver Moon lunar eclipse 2021: When and how to see it Nov. 19

The partial lunar eclipse, when Earth's shadow covers 97% of the full moon, will be the longest of the century by far, dwarfing the duration of the longest total lunar eclipse this century, which took place in 2018 and stretched to 1 hour and 43 minutes. The forthcoming eclipse will also be the longest partial lunar eclipse in 580 years, according to the Holcomb Observatory at Butler University, Indiana.

To prepare for the Beaver Moon lunar eclipse of 2021, check out our guide on how to photograph the moon with a camera. If you need imaging gear, consider our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography to make sure you're ready for the next eclipse.

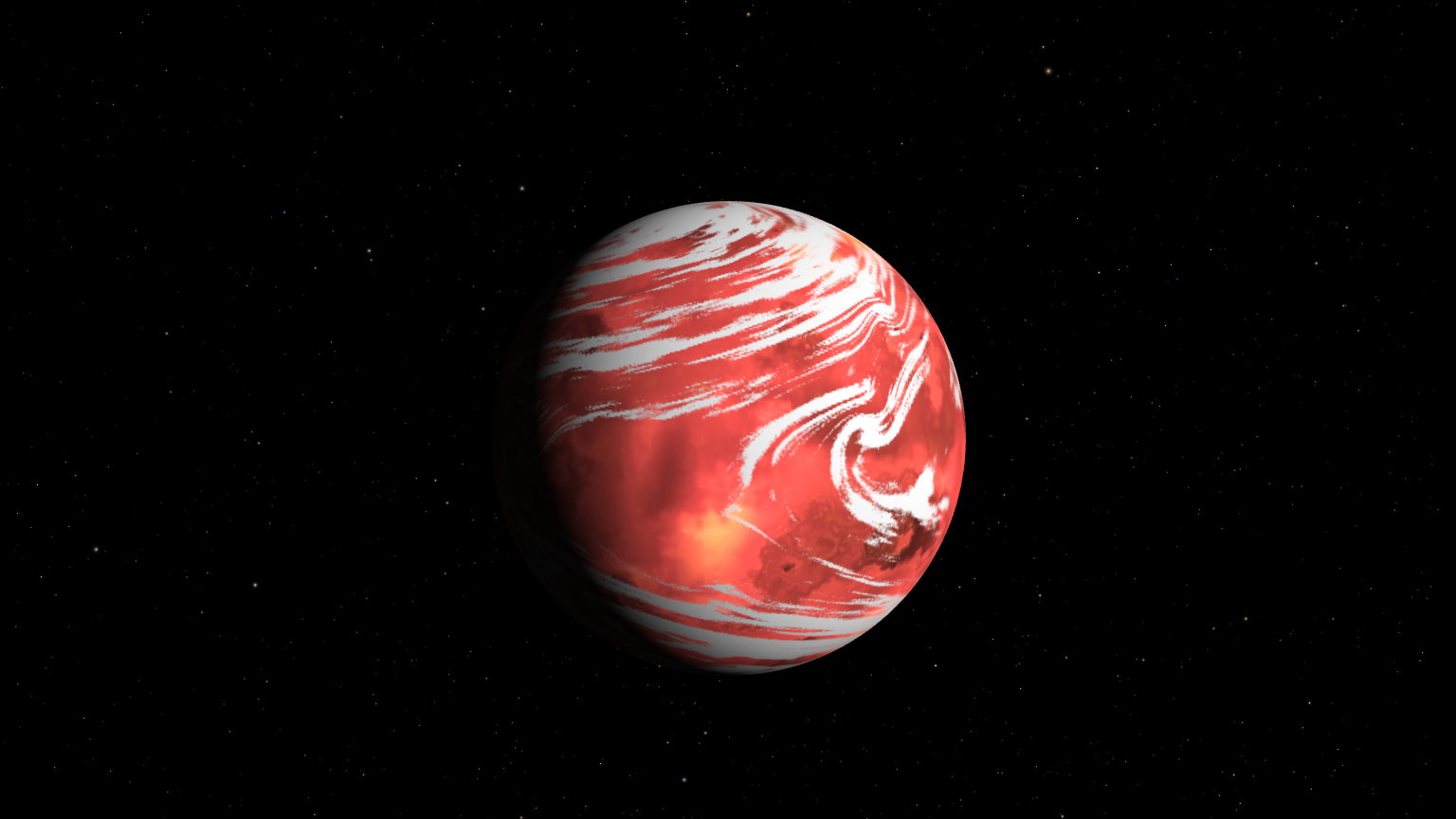

Lunar eclipses happen when Earth slides between the moon and the sun, so that our planet's shadow eclipses or "falls on" the moon. The shadow can block all, or in the case of a partial eclipse most, of the sun's light and paint the moon a dark, rusty red.

This reddening of the moon happens because light from the sun, despite being directly blocked by Earth's umbra, or the darkest part of its shadow, bends around our planet and travels through our atmosphere to reach the moon. Earth's atmosphere filters out shorter, bluer wavelengths of light and allows red and orange wavelengths through, Live Science previously reported. After these red and orange wavelengths pass through Earth’s atmosphere they continue traveling to the moon, bathing it in deep, mahogany-red light.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: Photos: 2017 Great American Solar Eclipse

To get exact eclipse timings for your location, you can visit timeanddate.com. The eclipse will be visible from North America and the Pacific Ocean, Alaska, Western Europe, eastern Australia, New Zealand and Japan. Though the early stages of the eclipse occur before moonrise in eastern Asia, Australia and New Zealand, eclipse-watchers in these regions will be able to see the eclipse as it reaches its maximum. Conversely, viewers in South America and Western Europe will see the moon set before the eclipse is at its peak.

Unfortunately, none of the eclipse will be visible from Africa, the Middle East or western Asia. Other areas may find clouds blocking the view of the moon, so checking weather reports ahead of a planned viewing is a must.

If you happen to miss this one, fear not, lunar eclipses tend to happen twice a year, and there will be a full lunar eclipse between May 15 and 16, 2022, followed by another one between Nov. 7 and 8, later that year, according to timeanddate.com.

Live Science would like to publish your partial lunar eclipse photos. Please email us images at community@livescience.com. Please include your name, location and a few details about your viewing experience that we can share in the caption.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like weird animals and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.