NASA's Lucy asteroid spacecraft still has a wonky solar array as it flies through space

"Except for this problem, the spacecraft is really kicking butt."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Three months after launch, a new NASA asteroid spacecraft is still getting settled into its life beyond Earth.

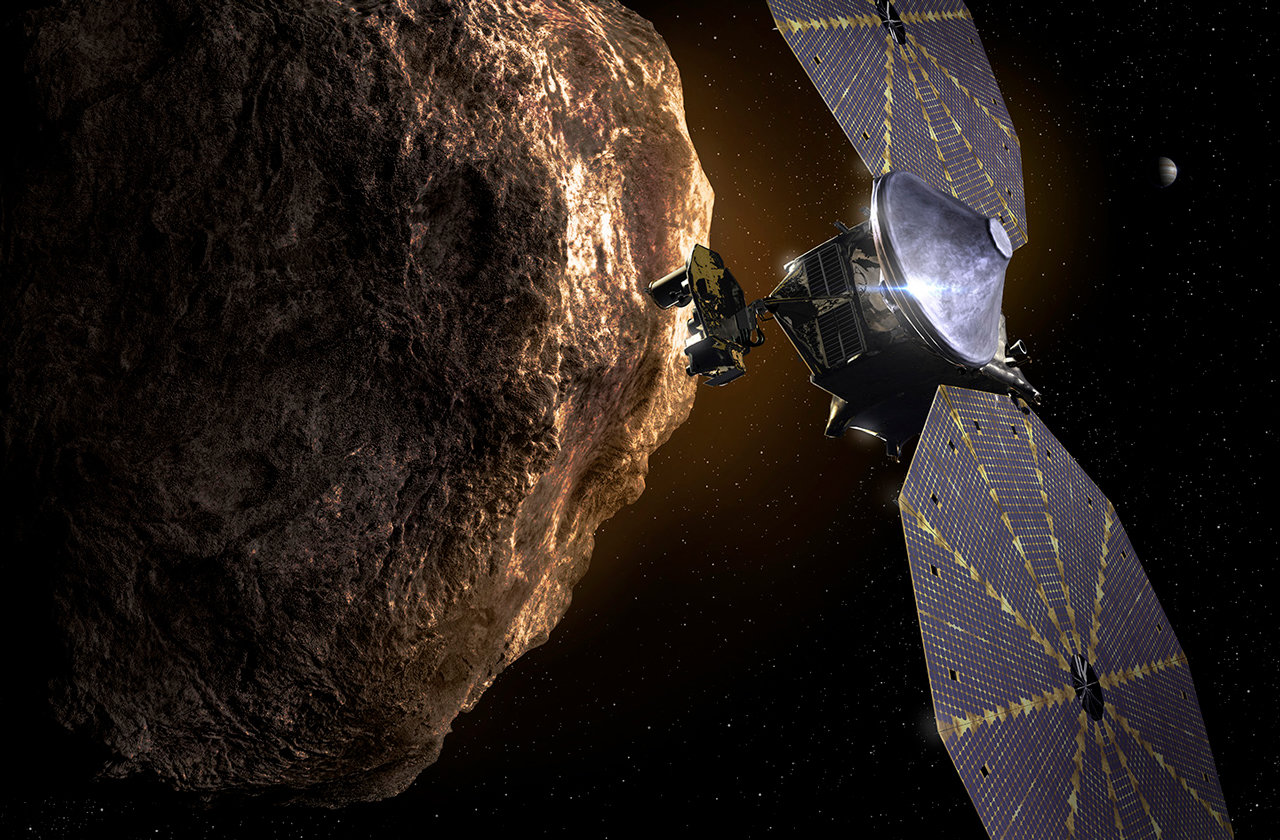

NASA's Lucy mission launched Oct. 16 with a mission to explore the Trojan asteroids, which orbit the sun ahead of and behind Jupiter. No spacecraft has ever visited the Trojan asteroids, which scientists believe are "fossils" from the formation of the solar system. But soon after launch, although the rest of the spacecraft's work has gone smoothly, the mission team realized that one of the spacecraft's two large solar arrays hadn't fully deployed.

"People have been working day and night since the launch to try to figure out what's going on, and I think we understand it," Hal Levison, principal investigator of the Lucy mission and a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado, said on Tuesday (Jan. 25) during a presentation to NASA's Small Bodies Advisory Group, which provides independent recommendations to the agency about studying moons, asteroids, comets and the like.

Related: Meet the 8 asteroids NASA's Lucy spacecraft will visit

However, Lucy is remaining in orbit around Earth for about a year before moving deeper into the solar system, and the arrays are much larger than they need to be in the relatively sunlit environment, so the situation isn't urgent.

"We have plenty of time, really, because we're not scheduled to fire the main engines for a while and we're in cruise," Levison said. "So we're taking our time to carefully go through our options."

Levison also said that Lucy's current power production is sufficient to meet the mission's needs throughout the journey. "The good news is that means we're producing over 90% of the expected power, it's actually 92 or 93[%]," Levison said. "So power is not an issue for the spacecraft — nor will it be through the entire mission if we have to fly it like it is."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Lucy's two large solar arrays were folded up for the spacecraft's launch, then began deploying "like a Chinese fan," as team members describe the process, into a decagon. Each array spans 24 feet (7 meters) and is opened by a lanyard rigged up to motors.

One deployed completely, with the full 360 degrees unfurled and a latch closed to hold the array in place; the team's estimate suggests that the second array is a little less than 350 degrees deployed, preventing latching. Analysis completed since launch has suggested that an issue with the lanyard meant to pull the array open prevented full deployment.

"Through some unknown process, there was a period where there was no tension on the lanyard as it was deploying," Levison said. "As a result, the lanyard fell off the spool. We think there's something like 30 inches [76 centimeters] of lanyard remaining to be pulled in."

The Lucy team is evaluating two options, he noted, adding that, "both of them, I think, have a significantly good chance of success."

One approach would attempt to finish deploying the temperamental solar array, turning the motors that work the lanyard back on.

"We're almost there, so I think if we can just pull a little harder, we might be able to get it all to latch," Levison said. However, the team doesn't want to rush this option. "We're running it in a way it wasn't designed to run, so we've been spending quite a bit of time analyzing the risks in trying to do this redeploy."

The other potential approach is to do nothing, since the solar array can meet the spacecraft's needs as it is. However, that would leave a gap in the array, like a missing pie slice, and would also leave the array without the support of the closed latch.

"We have plenty of power; the issue is the structural integrity of the array during main engine burns," Levison said. "The forces and torques going through the array and particularly where it's connected to the spacecraft are different than designed."

That distinction means that the team is building models and conducting analysis of what the spacecraft might experience during a main engine burn to ensure that leaving the array as is wouldn't damage the spacecraft, Levison said.

"The instruments and spacecraft are all behaving nominally," Levison said. "Except for this problem, the spacecraft is really kicking butt."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.