Lyrid Meteor Shower 2019 Peaks Overnight Tonight and Monday!

Look for bright meteors in the early hours.

Look up: It's the Lyrid meteor shower!

Different skywatching organizations have been pinning the meteor shower's peak on different nights as it continues through both April 21-22 and April 22-23. Whichever night you look, here are some tips for viewing the burning-up dust and debris left behind by Comet Thatcher in its trek around the solar system. Skywatchers can expect to see about 18 meteors per hour, though the bright moon may make them difficult to spot, NASA meteor expert Bill Cooke told Space.com.

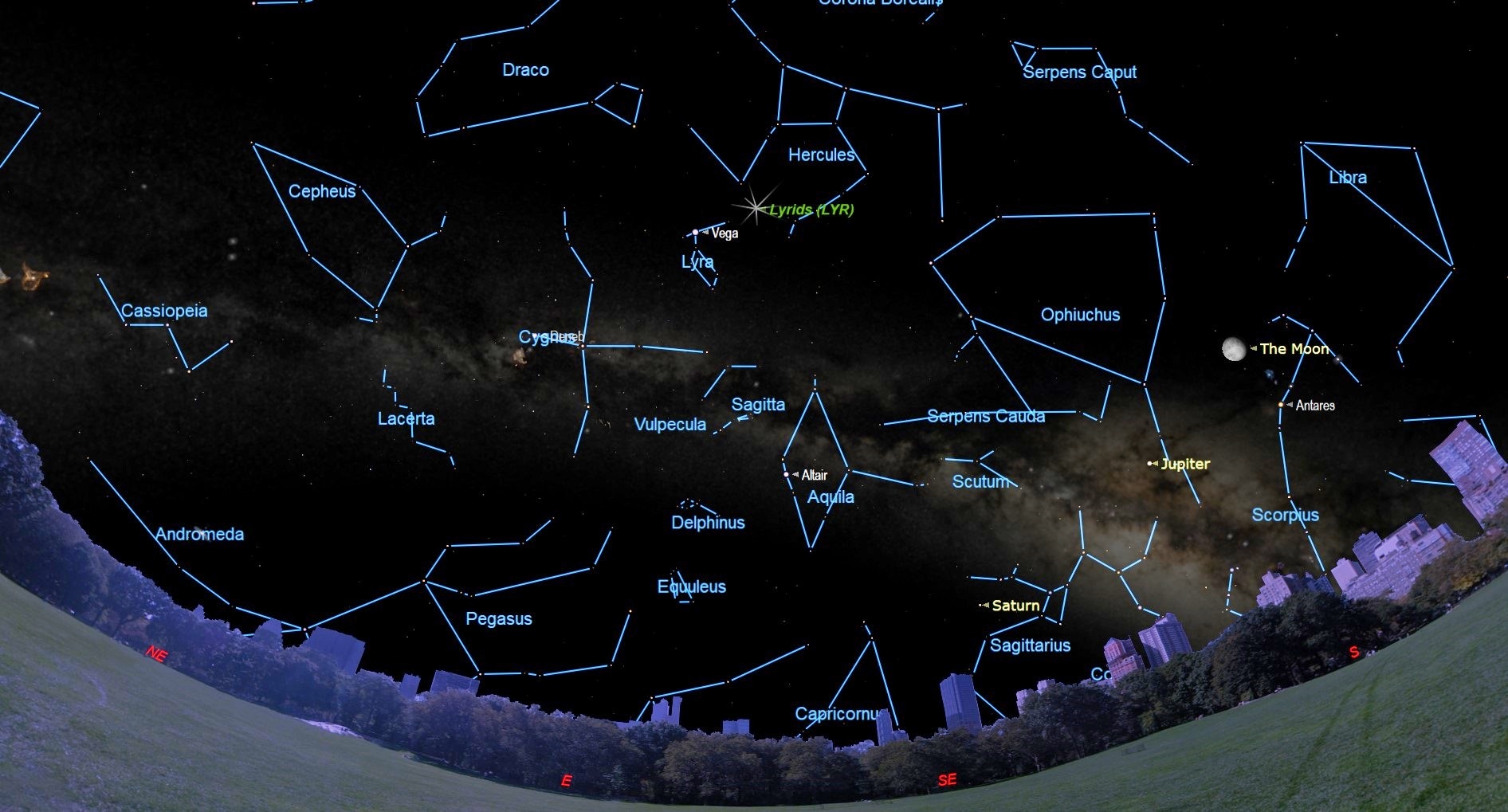

Meteor showers like the Lyrids occur when Earth passes through the dusty trail left behind by a comet. The meteors can appear all across the sky, but they seem to streak out of a spot to the northeast of the bright star Vega (called the meteor shower's radiant). This meteor shower is easier to see in the Northern Hemisphere because that part of the sky is high above the horizon before dawn, although you can see a lower rate from the Southern Hemisphere.

Related: Lyrid Meteor Shower 2019: When, Where & How to See It

People in the Northeast will see the radiant rise around 9 or 10 p.m. in their local time zones, and it will continue to climb in the sky throughout the night — but the moon will also rise soon after, so you could try to spot meteors within that window. (The moon rises earlier the night of April 21 than the night of April 22.) Otherwise, going out closer to 3 or 4 a.m. will put the radiant in the best spot for you to see meteors, although they'll be washed out by the moon.

Regardless of when you look, the key to watching a meteor shower is to go somewhere as dark as possible and make sure you give your eyes enough time to adjust — don't just dart outside to look at one; allow 20-30 minutes to adjust. Be sure to dress warmly, if you're somewhere cold, and get somewhere comfortable to sit where you can lean back and look at the whole sky. Because meteors can appear all across the sky, the naked eye is the best tool you can use; telescopes and binoculars will narrow your view.

Don't look directly at the radiant; meteors coming from farther away are more likely to have long, striking tails. The Lyrids hit Earth's atmosphere traveling as fast as 30 miles per second (49 kilometers per second), and can shine about as brightly as the stars in the Big Dipper, Cooke said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cooke told Space.com that the Lyrids do occasionally produce outbursts of as many as 100 meteors per hour, but that those bursts are unpredictable. Still, some skywatchers might try their luck despite the brightly shining moon.

The Lyrids' source, Comet Thatcher, orbits the sun about once every 415 years. Luckily for skywatchers, though, Earth passes through its path every year in mid- to late April. The resulting display has been observed at least as early as 687 B.C. — it's one of the earliest recorded showers. Comet Thatcher most recently passed by the sun (and Earth's neighborhood) in 1861, and it'll next pass by in 2276.

- Infographic: How Meteor Showers Work

- How to See the Best Meteor Showers of 2019

- A Brief History of the Lyrid Meteor Shower

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.