A Million Geysers of Plasma Spout from the Sun, and Scientists May Finally Know Why

When it comes to the mystery behind what causes jets of solar plasma that regularly erupt from the sun, clues have now emerged suggesting magnetic clashes on the surface of the sun may be the culprits, a new study finds.

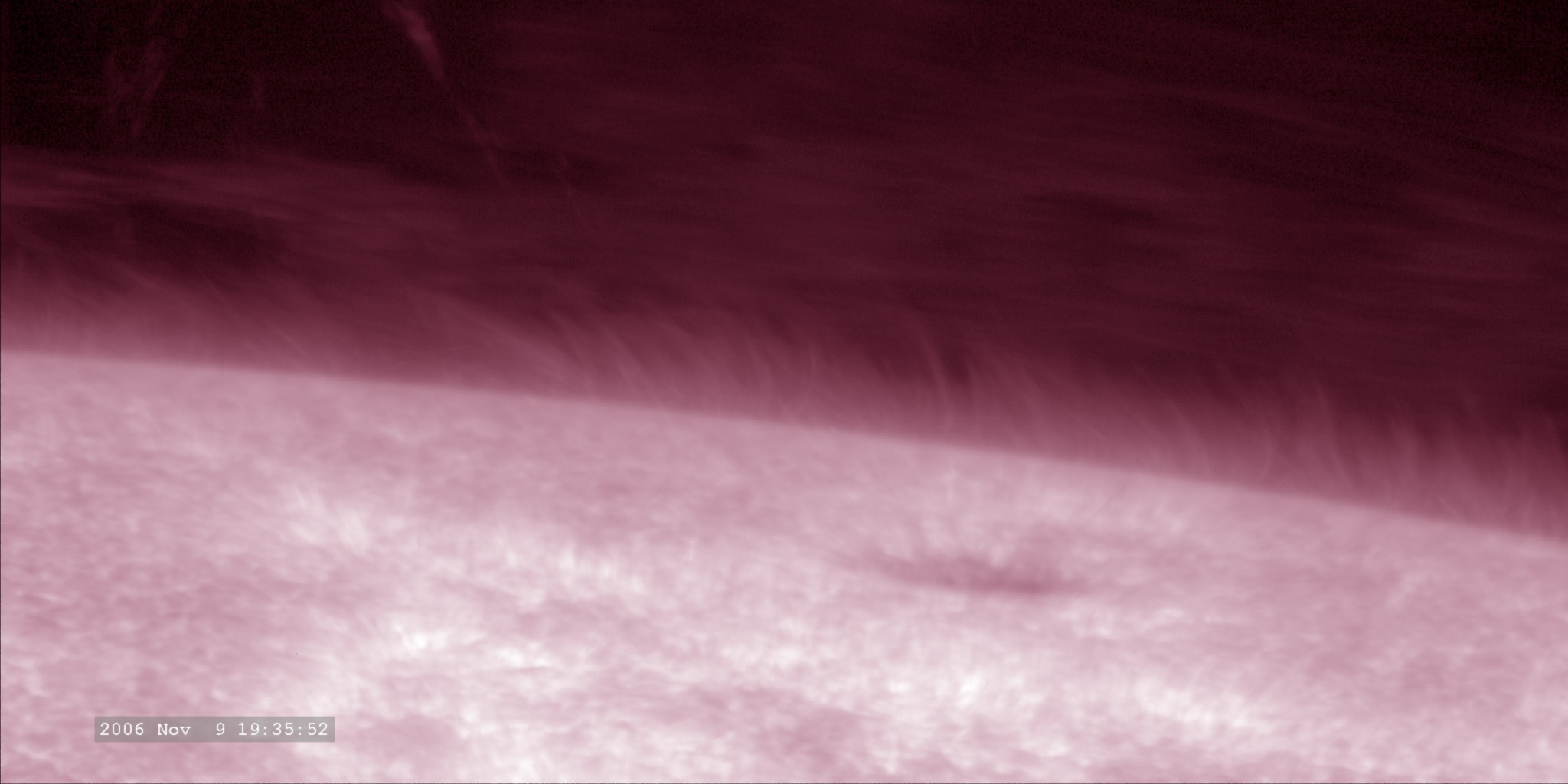

These findings may also help shed light on the puzzle of why the fiery halo of the sun is so much hotter than its visible surface, researchers said. At any given time, about a million geysers of plasma dot the chromosphere, the sun's lower atmosphere. Previous research has found these outbursts, known as solar spicules, can get hotter than 180,000 degrees Fahrenheit (100,000 degrees Celsius).

"We've seen them for about 140 years, but we don't know what drives them," study co-author Alphonse Sterling, a solar astrophysicist at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, told Space.com of these structures.

Related: Scientists' Favorite Sun Photos by Solar Dynamics Observatory

Other prior work has suggested that these spicules might help explain why the corona, the sun's outer atmosphere, is so much hotter than its underlying layers. Whereas the photosphere, the sun's visible surface, reaches about 10,000 F (5,500 C), and the chromosphere is a bit cooler at about 7,800 F (4,320 C), temperatures in the corona can range from 1.7 million F (1 million C) to more than 17 million F (10 million C).

Although spicules were discovered in 1877, their origins remain a mystery because of their brief nature. They often last less than 12 minutes, with solar plasma moving at speeds between 33,550 to 89,475 mph (54,000 to 144,000 km/h). Some are even faster, dispersing in less than a minute and traveling at about 223,690 mph (360,000 km/h).

Now, using the Goode Solar Telescope at the Big Bear Solar Observatory in California, researchers have discovered clues about how spicules form.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This telescope is the highest-resolution solar telescope ever built in the United States," study co-author Wenda Cao, director of the Big Bear Solar Observatory and a solar physicist at the New Jersey Institute of Technology in Newark, told Space.com. "You need a high-resolution telescope with high sensitivity to see features like spicules, which are very small, narrow features on the sun."

Related: What's Inside the Sun? A Star Tour from the Inside Out

The researchers found that many spicules emerged within a few minutes of the formation of a patch on the photosphere with a magnetic field reversed from its surroundings. For example, spicules would often erupt from a patch that was mostly polarized magnetic north shortly after it appeared within a region that was mostly polarized magnetic south.

According to the scientists, these findings suggested that spicules might form because of an effect known as magnetic reconnection. When two magnetic regions with differently oriented field lines encounter each other, those magnetic field lines can clash, break and reconnect with each other, explosively converting magnetic energy to heat and kinetic energy.

Previous findings suggested that magnetic reconnection may also cause similar, larger outbursts, such as coronal jets, solar flares and coronal mass ejections, Sterling said. "The same processes that drive these large-scale eruptions may drive spicules also," he said.

Data from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory also revealed that after spicules formed, the overlying corona became hotter, according to the researchers. "Spicules may serve as the key to solving the coronal heating problem," Cao said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Nov. 15 issue of the journal Science.

- Amazing New Sun Photos from Space

- NASA Telescope Snaps Best-Ever Pictures of Sun's Atmosphere

- The Sun in HD: Latest Photos by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us