Lost space dreams: How Al Crews missed out on becoming an astronaut — twice

Crews was in line to fly on two military spacecraft that never made it to orbit.

A half-century ago, on a warm July evening, Albert Crews was sitting in front of a television set in his California home, sharing a communal experience with millions of others around the globe: watching Neil Armstrong take humanity's first steps on the moon.

As Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin explored the lunar surface, Crews was left to ponder: What if?

He had twice been selected as an astronaut, twice been extensively trained to pilot spacecraft into orbit, and twice had his space projects canceled, the second one terminated just weeks before the historic Apollo 11 lunar landing.

Related: Manned Orbiting Laboratory: Inside a US military space station

Albert Hanlin "Al" Crews Jr. was born in 1929 in El Dorado, Arkansas. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in chemical engineering at the University of Southwestern Louisiana and, following graduation in 1950, joined the U.S. Air Force. Trained as a pilot, Crews was assigned to a fighter squadron, based in Tripoli, Libya, for about 2 ½ years.

Crews enrolled in graduate school to study aeronautical engineering. The Soviet Union launched Sputnik. NASA selected the seven original Mercury astronauts. Al Crews knew what he wanted to do next.

"When NASA picked the seven (Mercury) astronauts, that impressed me. I decided then that I wanted to be an astronaut," Crews said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

At that time, the only path to outer space ran through the birthplace of "The Right Stuff," California's Edwards Air Force Base. Crews applied, and was accepted, into the highly competitive Air Force Experimental Test Pilot School, graduating in 1960.

"The Air Force nearly always picked people out of Fighter Test at Edwards for the space program or anything special like that," Crews recalled.

"Usually the top two or three in the (test pilot) class would stay at Edwards," he added. When we went to work at Test Ops, whoever had been there the longest got the first choice of an assignment."

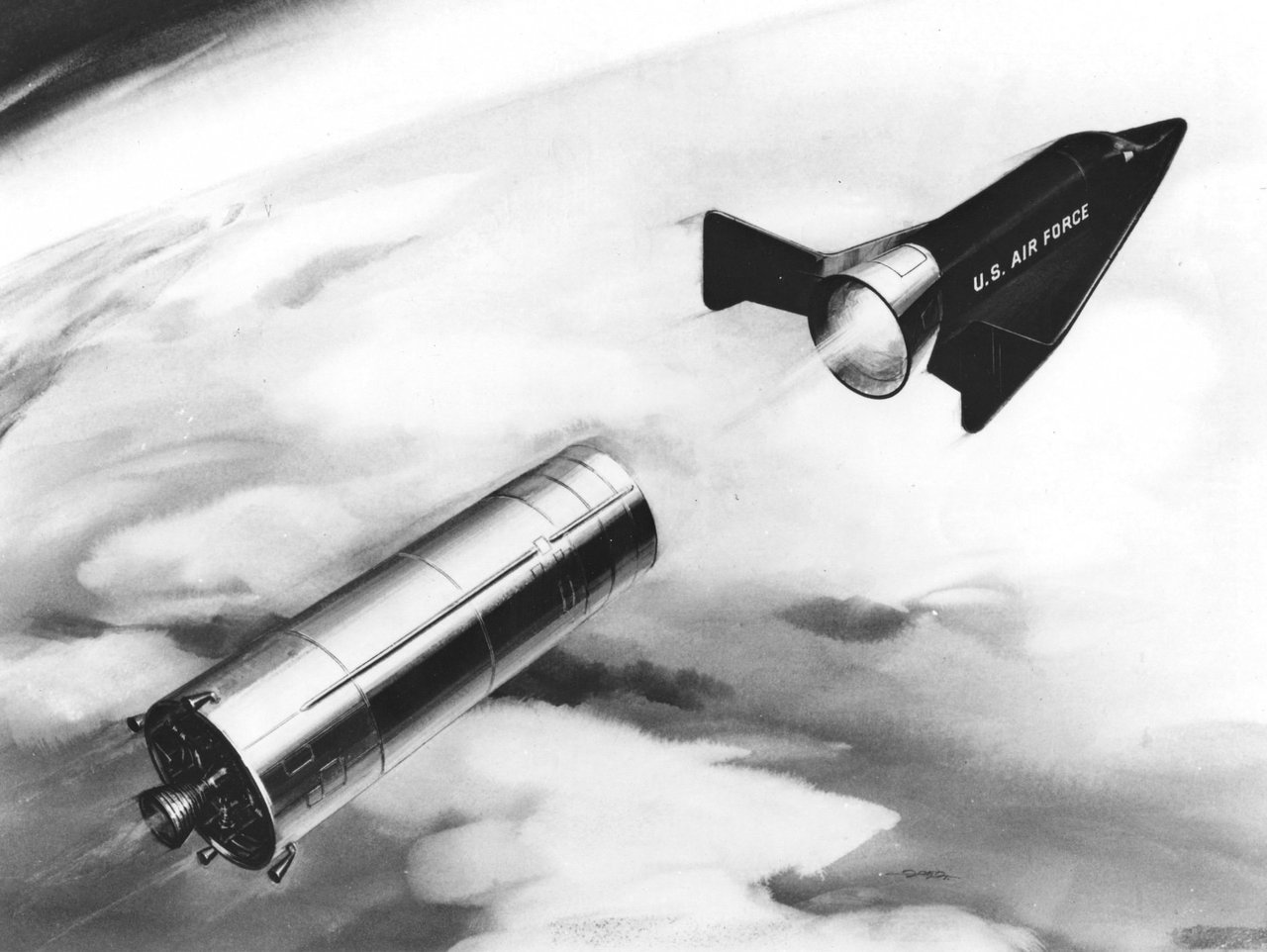

That assignment turned out to be the Air Force's embryonic space plane, named "Dyna-Soar," which was somewhat of a cross between a twin-tailed, delta-winged fighter jet and NASA's future space shuttle.

Conceived in the late 1950s, Dyna-Soar was to be cutting-edge technology, constructed of super alloys with a graphite and zirconia composite nose cap.

Related: Space Planes: Evolution of the winged spaceship (Infographic)

Designed by Boeing, Dyna-Soar would be launched into a suborbital trajectory by a Titan I (and later, Titan II) intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). The 35.5-foot-long (10.8 meters) spaceplane, with its sharply swept delta wings, would perform a variety of military and reconnaissance missions, reenter the atmosphere, then glide back to Earth under the control of its pilot-astronaut.

While "Dyna-Soar" is a seemingly unusual name for a spacecraft, in fact, it was highly descriptive of the vehicle's mode of flight: "dynamically soaring" through the Earth's atmosphere using the energy generated from its reentry and the maneuverability offered by its aerodynamic design.

"The choice of flight paths available to the Dyna-Soar pilot will be almost infinite,'' said George Stoner, Boeing's Dyna-Soar program manager, in September 1960. "By combining the high speed and extreme altitude of his craft with his ability to maneuver, he will be able to pick any airfield between Point Barrow, Alaska, and San Diego, California, with equal ease."

However, in late 1961, under the direction of Robert McNamara, President John F. Kennedy's new secretary of defense, Dyna-Soar's mission was changed. The Dyna-Soar space plane, now designated the X-20, would be launched into Earth orbit.

At a time when the United States' spaceflight capabilities consisted of launching NASA's Mercury capsules into a ballistic suborbital arc and parachuting into the ocean, Dyna-Soar's planned capabilities were to be far more advanced.

The Air Force Chief of Staff, Gen. Curtis LeMay, said on Oct. 26. 1961, "Since space systems are extremely expensive, one of the first tasks of a manned space vehicle would be to repair equipment operating in our unmanned satellites."

Dyna-Soar's newly defined mission would now require the use of the powerful Titan III space booster, still under development, to reach orbit. As envisioned, the first crewed flight was to take place in August 1965. Dyna-Soar would be launched into orbit from Cape Canaveral, Florida, reenter the atmosphere, and glide to a landing on the dry lakebed at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

"This military test system (X-20) has the capability for manned, maneuverable, hypersonic reentry from orbital altitudes and velocities with a normal landing at conventional airfields," Undersecretary of the Air Force Joseph Chanyk boasted at the time.

In September 1962, Crews was selected as Neil Armstrong's replacement on the X-20 Dyna-Soar program, joining five other test pilots secretly selected two years earlier.

In a recent interview with Space.com, Crews spoke about his decision to join Dyna-Soar.

"The X-20 had four Air Force test pilots on the program; when they were looking at new pilots, they first went to [future Gemini and Apollo astronaut] Jim McDivitt," Crews said. "He decided that he'd rather go to NASA, so then they offered it to me. At that time, I thought it [Dyna-Soar] was a much better deal than going to NASA."

Unlike his Dyna-Soar colleagues, Crews' selection was announced to the news media, and his fellow astronaut candidates were also introduced for the first time.

"It was about the same time that I was selected, they decided to announce the program freely. Parts of the program had been classified, but they decided to open it up and made the announcement," Crews said.

"The Commandant of the Air Force and the Air Force Chief of Staff were at an Air Force Association meeting in Las Vegas. They had a mock-up there of the X-20, and there was a photo session with the crew members, five Air Force and one NASA."

Crews and his fellow test-pilot-astronauts flew simulated X-20 landing profiles using high-performance F-104 fighter aircraft, developing the pioneering techniques required to safely glide a space plane back to Earth.

"What we learned flying the F-104 was, if you flew faster, you could flare the vehicle; then, if you screwed up, you could re-flare," Crews recounted. "You'd change the aiming point back about a mile short of where you actually wanted to touch down. Then, you'd fly level for about five or 10 seconds before touching down. It made it a lot easier to make a good landing."

Unfortunately for Al Crews and the rest of the Dyna-Soar team, however, Defense Secretary McNamara was no longer convinced of the need for a piloted military space plane.

Related: Military Space - Spacecraft, Weapons and Tech

Dyna-Soar had been under close scrutiny within the Defense Department for its lack of a viable military mission and very narrow project objectives. The government had spent $410 million on a still-unflown research and development vehicle to study reentry from orbit, dynamic soaring and powerless landing. NASA's new Gemini spacecraft, then under development, provided much more capability (and value) as an operational space vehicle, McNamara concluded.

So, on Dec. 10, 1963, less than a month after President Kennedy's assassination, McNamara canceled the X-20 Dyna-Soar program.

"It was decided to terminate the Dyna-Soar X-20 program because the current requirement is for a program aimed directly at the basic question of man's utility in space, rather than a program limited to finding means to control the return of man from space," McNamara said at the time. "The Dyna-Soar program was designed to do the latter."

The Air Force hierarchy was not pleased with McNamara's decision to cancel Dyna-Soar, believing that a military human spaceflight program was a necessity, not a luxury. So Air Force officials proposed an alternative, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL).

Related: Manned Orbiting Laboratory: A military space station (Infographic)

"Although the X-20 reached the mockup stage and $410 million was spent on its development, the program was canceled by the government. Congress directed that X-20 funding be diverted to the Manned Orbiting Laboratory," representatives of aerospace giant Boeing, the prime contractor for the X-20, recapped in a later press release. "The partially completed X-20 prototype and the mockup were scrapped, as well as initial tooling set up for a production line for 10 space planes."

Overnight, Crews was no longer an astronaut. For the first time.

Crews believed that the X-20 was less than three years away from its first flight when the program was canceled, and he points the blame directly at McNamara.

"They [Boeing] had it all designed, and had built some of the parts, but not very many. Everything was on hold because of McNamara mostly; he was holding back for whatever reason he could," Crews said.

"One of the things he did … even though it was to be a research vehicle, McNamara decided that it should carry a payload. So he conned President Kennedy into approving a thousand-pound [450 kilograms] payload for Dyna-Soar, which then ruled out using the Titan II as a booster. This meant that it had to wait for the Titan III [to be developed]. Then, they were able to cancel it before the Titan III ever flew."

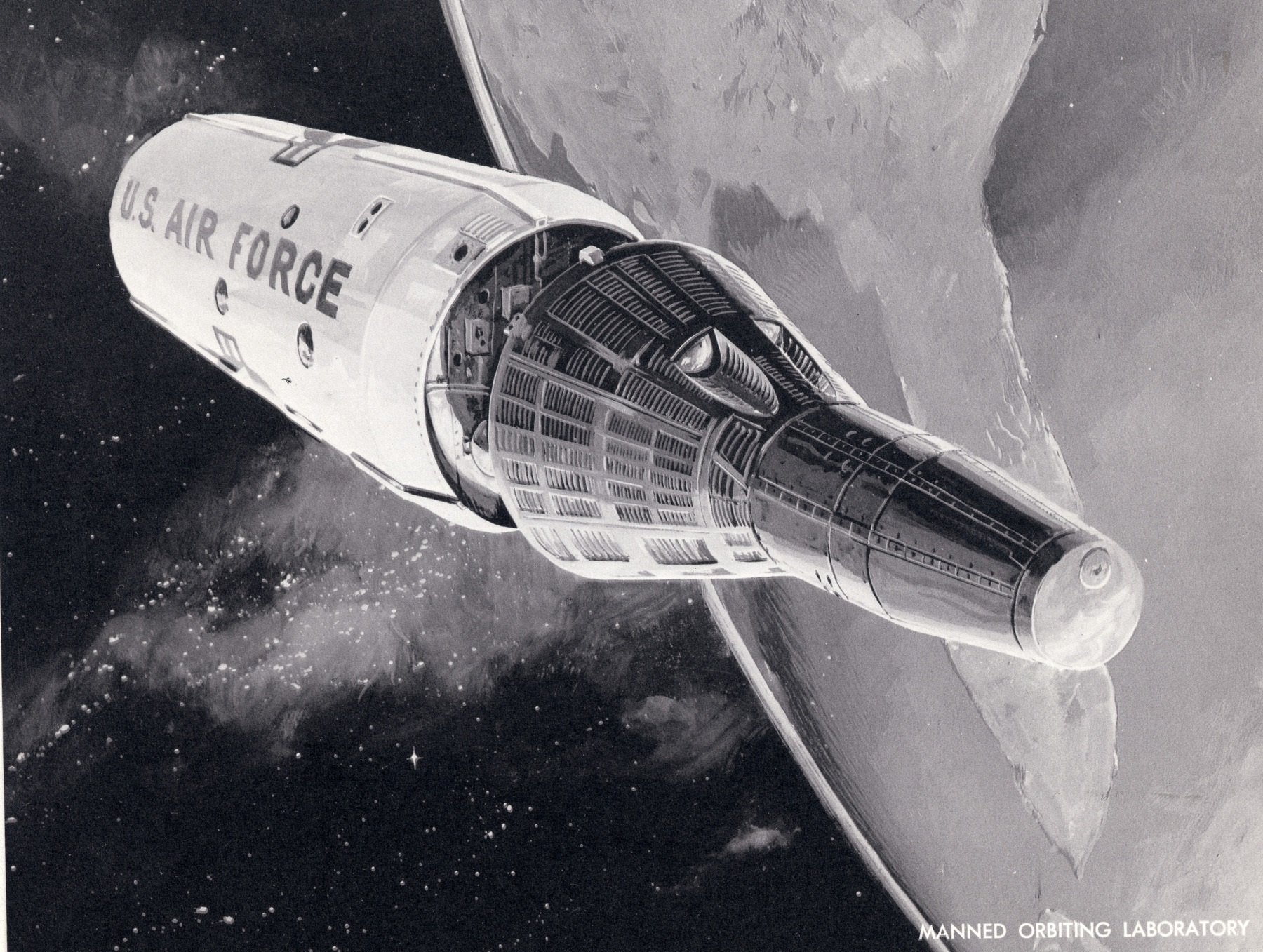

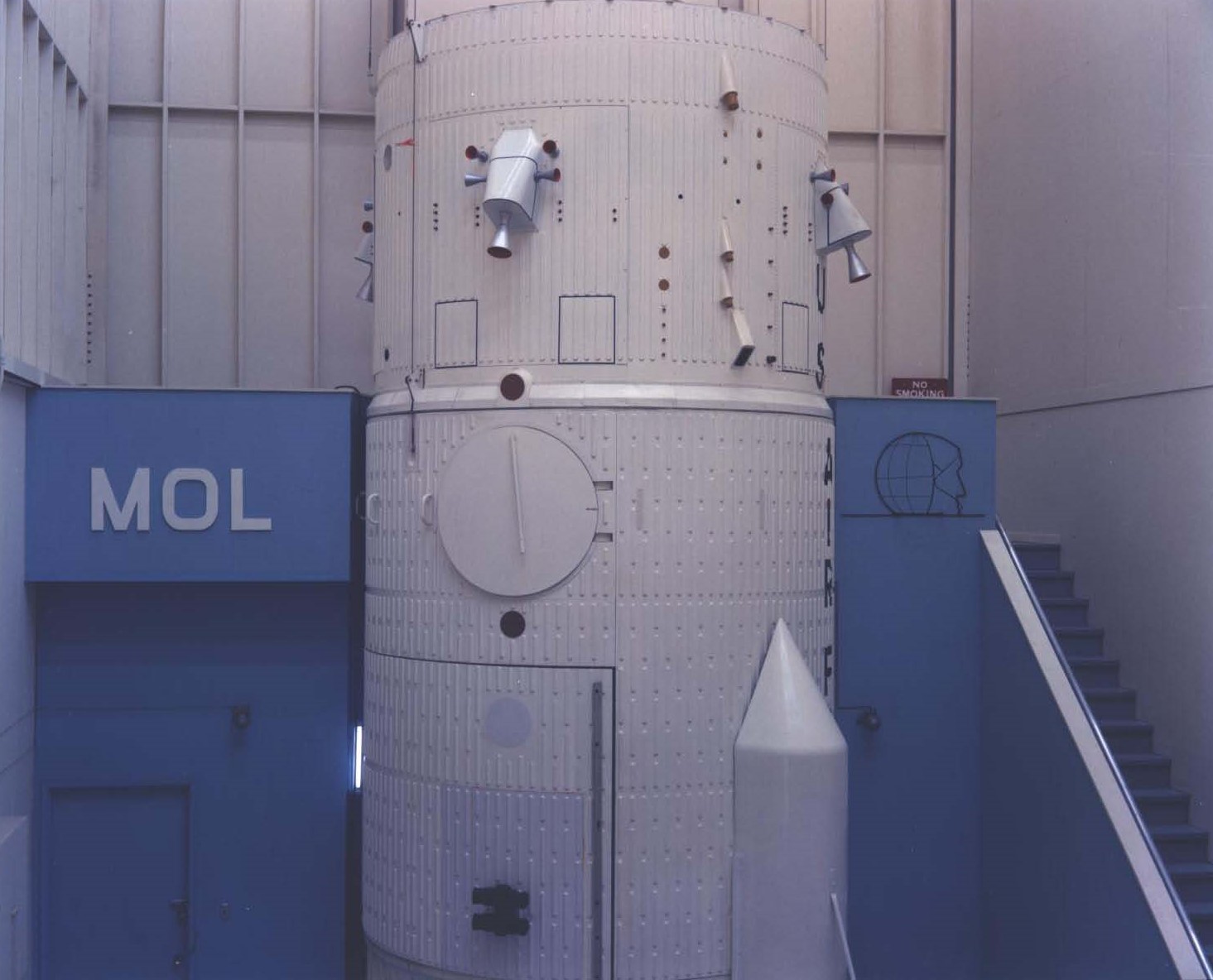

At the same news conference canceling Dyna-Soar, McNamara announced the commencement of the MOL program, which was described as "an orbiting pressurized cylinder approximately the size of a small house trailer, [which] will increase the Defense Department effort to determine military usefulness of man in space."

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory would be launched into a polar orbit from California's Vandenberg Air Force Base atop a powerful variant of the Air Force's Titan III space launch vehicle, the Titan III-M ("M" for "Manned").

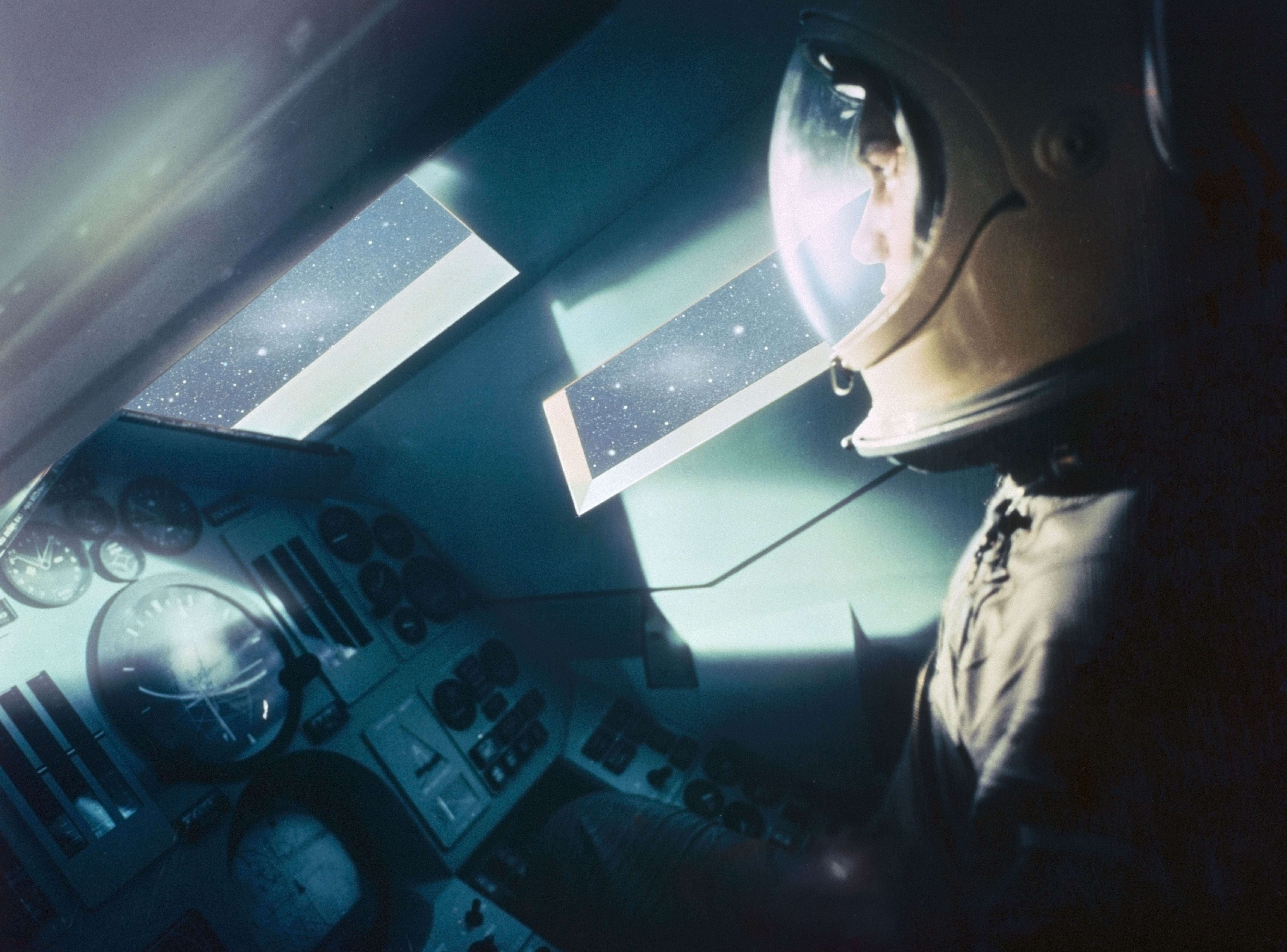

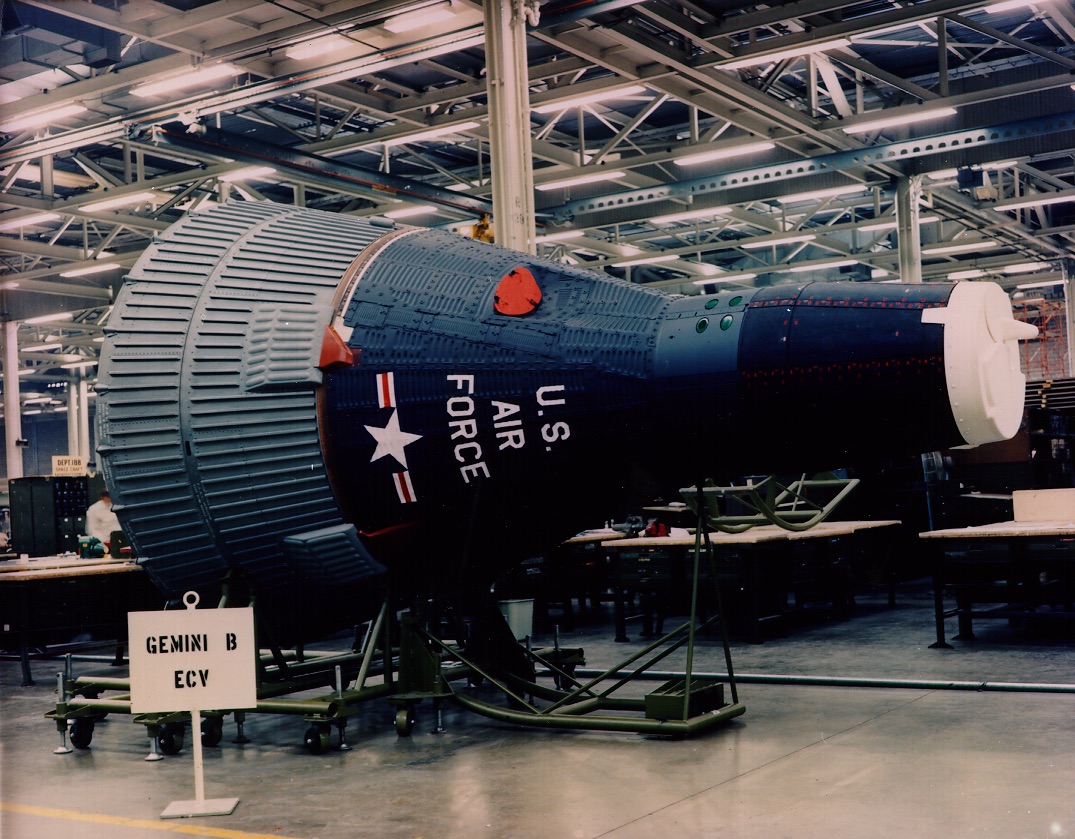

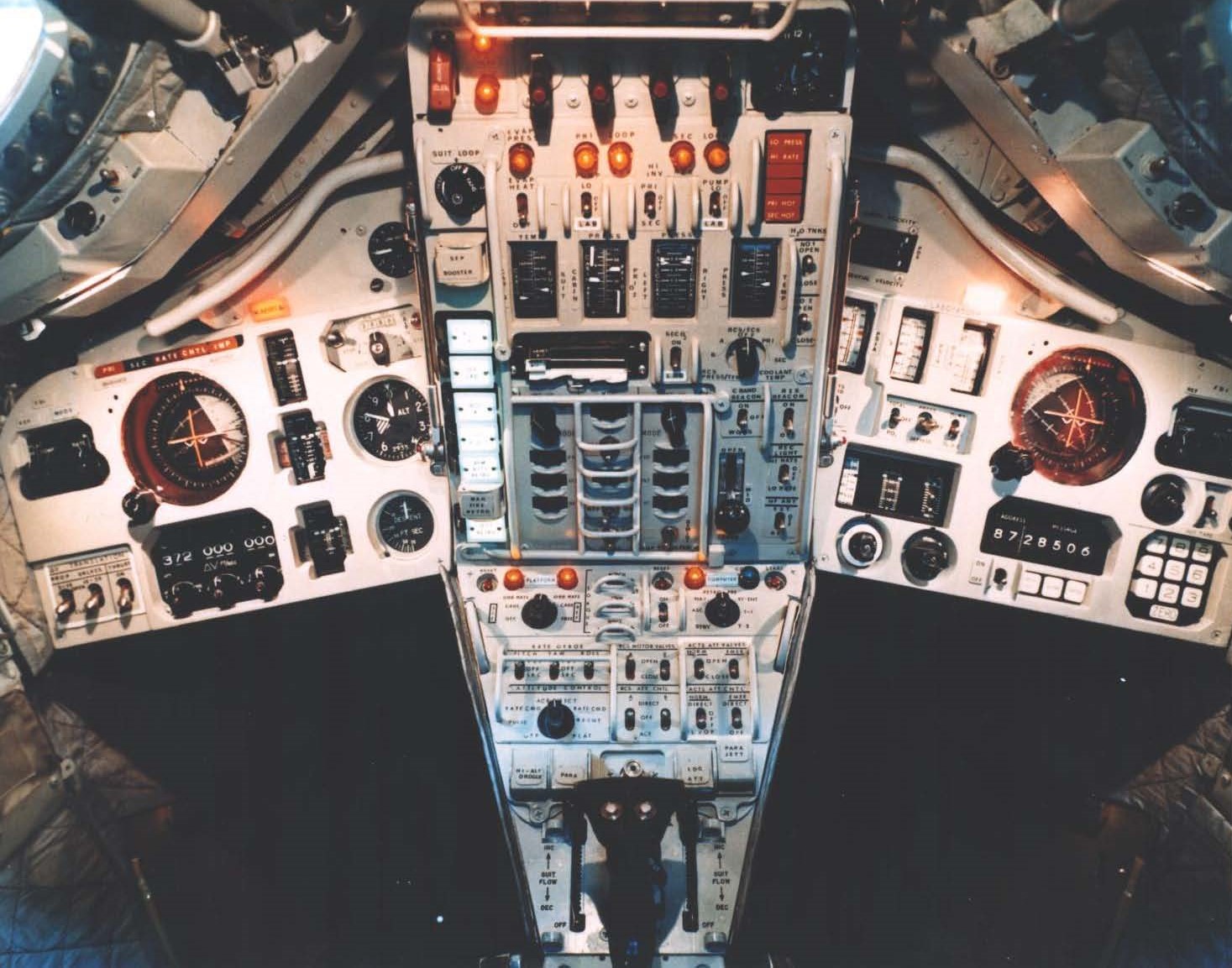

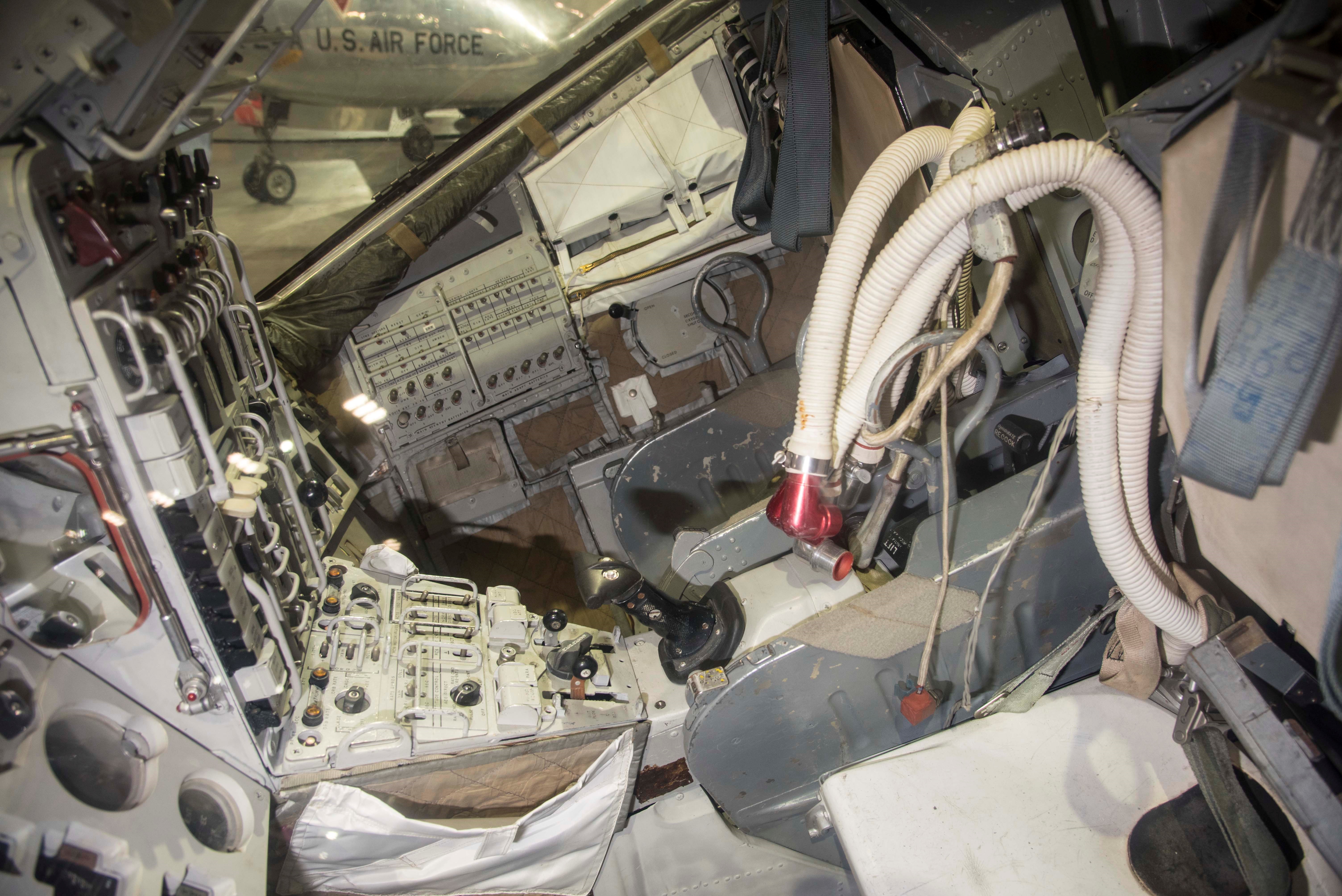

A pair of MOL astronauts would fly a modified Gemini spacecraft, the Gemini-B, quite similar to the spacecraft used by NASA for its two-man program but with a key difference: the Air Force version would have a hatch cut into its heat shield to enable the astronauts to enter the orbiting laboratory segment. Once inside, the 1,000-cubic-foot (28.3 cubic meters) pressurized laboratory would provide a "shirt-sleeve" working environment for the two-man crew to carry out experiments and observations during a 30-day mission.

Related: Manned Orbiting Laboratory Declassified: Inside a US Military Space Station (Photos)

Al Crews' luck was about to change again. The Air Force needed astronauts for the MOL program, and his name was at the top of the selection list.

"Four of the X-20 Air Force pilots were considered too old for MOL," Crews recalled. "Pete Knight (future X-15 pilot-astronaut) and I both said that we were available."

"They initially had everybody they were considering go down to Brooks AFB [to the Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine] for an examination. Pete had some kind of an eye problem, astigmatism, but they left me on. Everybody else they had lined up were a little bit younger than me."

"They had earmarked eight people and then kept us all waiting, from December 1963 to November 1965, before they decided to announce the flight crews," Crews said. "I had been almost the youngest guy on the Dyna-Soar program, so when we went on MOL, I was the oldest guy."

By August 1965, Air Force officials had agreed upon most of the details of the MOL program. Defense Secretary McNamara provided President Lyndon Johnson with an outline of the program, along with the cost – $1.5 billion for six MOL missions (one uncrewed, five crewed). The first crewed flight was targeted to take place in late 1967 or early 1968.

Johnson spoke enthusiastically about MOL, declaring, "This program will bring us new knowledge about what man is able to do in space. It will enable us to relate that ability to the defense of America. It will develop technology and equipment which will help advance manned and unmanned space flights."

In November 1965, the Air Force announced the selection of Crews and seven others as its first class of Manned Orbiting Laboratory astronauts. After the announcement, a senior Air Force officer reportedly told the eight men, "This is the first and last press conference you will ever attend."

Very little information was released publicly about each of the MOL astronauts; from that introductory press conference forward, their public exposure was limited and controlled. Crews and his colleagues were forbidden from giving interviews. All were "required at all times to maintain a high standard for moral, ethical and military conduct."

Even as the president and Air Force were issuing glowing proclamations about how MOL would "make it possible to perform new and rewarding experiments," they never disclosed the program's true mission: to serve as a manned orbiting reconnaissance platform for the top-secret National Reconnaissance Office (NRO).

After monthlong orbital missions, MOL astronauts would return to Earth in their Gemini-B spacecraft carrying "a substantial portion of the mission photographic product on-board." In the event of an off-target emergency landing, the astronauts "would be instructed to exercise U.S. sovereignty over all equipment and to refrain from providing information on the program or reconnaissance information collected to anyone during either incarceration or interrogation."

Incredibly, the eight MOL astronauts were never told about what they were actually signing up for: missions so secret than no MOL astronaut would be allowed to fly in combat for at least three years after departing the program.

Crews, in a recent oral history interview with the NRO, recalled the secrecy and lack of transparency in the MOL astronaut selection process.

"It was a very classified program, Crews said. "We weren't briefed on the program until after we were selected. Then we were told that we could leave if we didn't like what we were doing."

"I never knew anything about reconnaissance until we were selected, because they couldn't talk about it unless you had the proper clearance, and none of us had that clearance until after we were selected … We had been selected and were then at least a month into the program before we were ever briefed on the reconnaissance mission."

Related: Gallery: Declassified US Spy Satellite Photos & Designs

As military officers, the MOL astronauts all readily accepted their covert assignment. Soon, they started helping develop the spacecraft systems, hardware, software and orbital reconnaissance techniques, as well as learning about the complexities of living and working in space for long durations.

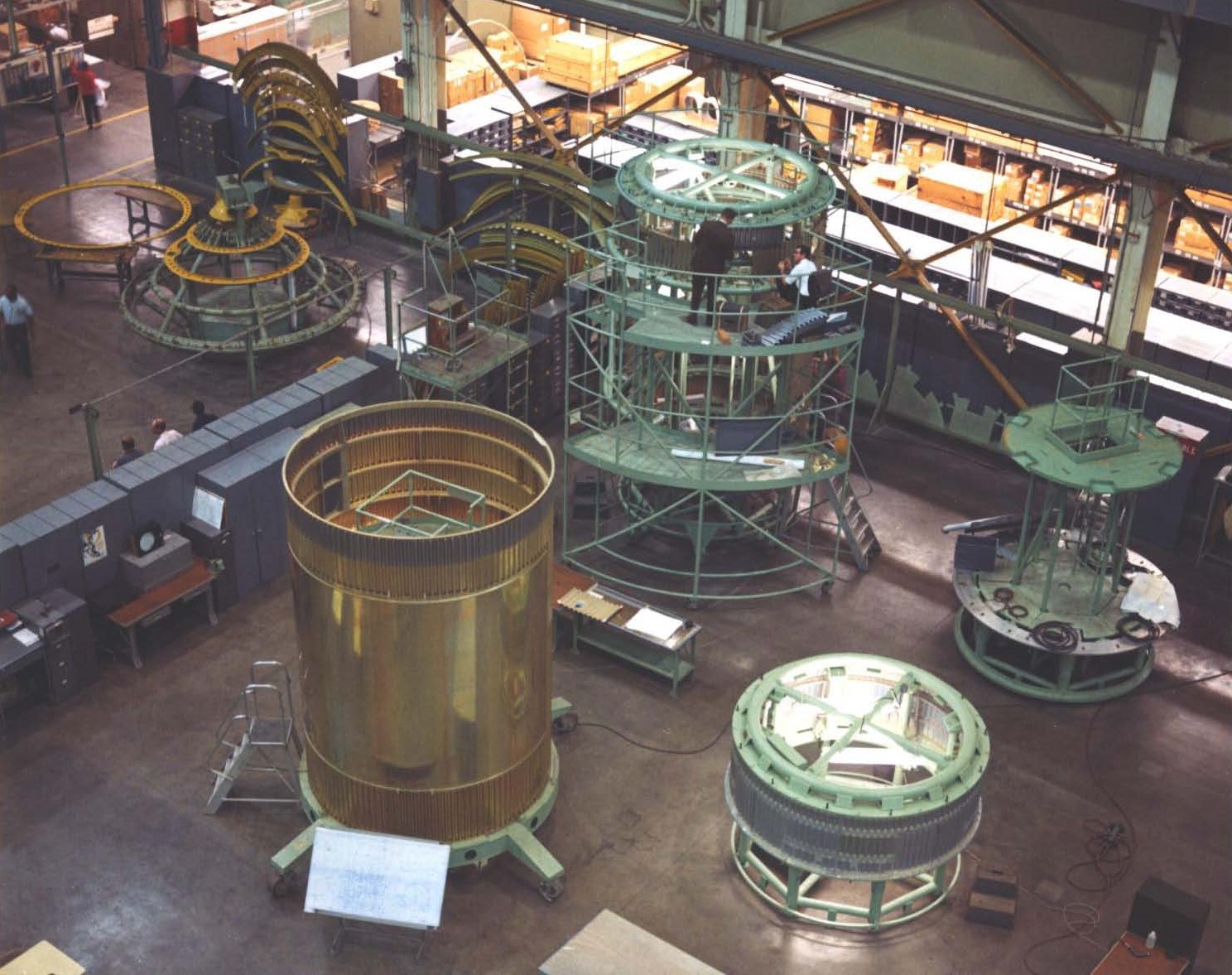

Douglas (soon to be McDonnell Douglas) and General Electric constructed expansive MOL assembly and test facilities to produce mock-ups, prototypes and the eventual fabrication of the Gemini-B spacecraft and orbiting laboratory modules. Eastman Kodak built an underground facility in Rochester, New York, to perform a straight-line visibility test to assess the laboratory's clandestine 6-foot (1.8 m) telescope mirror; an above-ground structure, rising high into the sky, would have been much too obvious to disguise in an effort to conceal it from the prying eyes of foreign intelligence agencies.

"General Electric had built an underwater facility in the Virgin Islands with a structure the size of the [MOL] laboratory, and they were demonstrating how to move equipment around in zero-G," recalled Crews. "All of us went down and used it. We all got checked out in underwater operations."

Crews was concerned that more money was seemingly being spent on facilities than building MOL flight hardware.

"There was no way I could ever know exactly how much anything cost, but I do know that as soon as Douglas was named as one of the contractors, they had all these people hired to work on it, and they built new buildings for all of them," said Crews. "I knew that General Electric built at least five buildings in Pennsylvania, plus the big underwater facility in the Virgin Islands … All of those kind of things had to cost a lot of money."

In November 1966, the MOL program accomplished a critical milestone. A Titan III launch vehicle lifted off from Florida's Cape Canaveral, which was then called Cape Kennedy, carrying a modified Gemini spacecraft. The Air Force obtained a previously flown Gemini capsule from NASA, cut a hatch into its protective heat shield, launched it to an altitude of about 190 miles (306 kilometers), and then commanded it to reenter the atmosphere. The spacecraft survived reentry, the heat shield worked as planned, the hatch remained intact and the flight was deemed a success. Ultimately, this was the only mission ever flown in the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program.

Engineers continued to refine the design of the laboratory module and the Gemini-B spacecraft. Highly skilled technicians and aerospace production workers toiled to fabricate, assemble, install, test and inspect the many parts that would make up the Manned Orbiting Laboratory. At McDonnell Douglas' massive MOL Assembly & Integration Building in Huntington Beach, California, large segments of the laboratory module were taking shape.

Crews and the other MOL astronauts were fitted for their blue spacesuits and tested them in the heat- shield tunnel assembly that would connect the Gemini-B and orbital laboratory segments.

"We used some of the NASA Geminis for fit-checks and for guessing … like when they were getting prepared to make the hole in the heat shield to transfer back to the lab, we used the NASA Geminis for measurements," Crews recalled.

"We were all measured [for spacesuits] and had suits built. We picked [MOL astronaut] Dick Lawyer to test the tunnel in the heat shield transfer; they did most of the testing in a zero-G airplane. Dick was our fattest guy; we figured if he could do it, we all could do it!" Crews said with a laugh. "So, they built his spacesuit first and then stored them at the Cape when they finished the test."

Decades later, in 2005, Lawyer's MOL spacesuit would be discovered in a closet in the Air Force Space Museum in Cape Canaveral.

MOL's ambitious mission requirements were becoming increasingly complicated and expensive. NASA's Apollo program was reaching its highest levels of funding necessary to achieve the national goal of a moon landing before 1970. The Vietnam War was rapidly escalating. Something had to give financially — and that something was MOL.

Related: Lunar Legacy: 45 Apollo Moon Mission Photos

Hardware and software development soon began to lag, training was postponed and projected launch schedules slipped. An optimistic first-launch date of early 1968 soon became 1970, then 1971, then 1972.

Even more ominous for the MOL astronauts, rapid advances in unmanned reconnaissance satellite technology were rendering their primary mission — human spies in space — obsolete.

Al Crews began to see the handwriting on the wall.

"Around 1967, I was invited to go to the meetings where the 'wheels' [senior officials] would get a briefing on the last unmanned system picture taking [photo reconnaissance satellite]," Crews said. "One of the satellites had flown over Los Angeles and took pictures of our parking lot."

Crews was stunned at the clarity of the images and the level of detail he could discern on the automobiles.

"I figured right then that we didn't have a program."

"It took two more years for MOL to end," Crews said. "But there was a large increase in unmanned reconnaissance] capability from the time we were selected until then."

"I think that the problems with the [budget] squeeze, no money to spend, Vietnam War, supporting NASA … the Air Force was just happy to have a program and not worry about the training that should be done. It soon became obvious that all we were was a backup in case the unmanned reconnaissance system didn't work."

By mid-1969, MOL's original price tag of $1.5 billion had ballooned to $3.2 billion (about $22.4 billion in 2020 dollars). The first flight was still three years away. The new Nixon administration wanted to cut spending, and the NRO had two very big, very expensive programs under development — MOL and the unmanned HEXAGON wide-area search reconnaissance satellite.

The Bureau of the Budget gloomily summarized, "Since 1965-1966 when the decision was made to pursue the MOL for its intelligence value, the relative benefit and the cost of the MOL have changed very significantly."

The decision was made to cancel the Manned Orbiting Laboratory.

On June 9, 1969, Deputy Secretary of Defense David Packard issued the memo that drove the final nail into MOL's coffin.

"The Air Force is hereby directed to terminate the MOL Program except for those camera system elements useful for incorporation into an unmanned satellite system optimized to use the TITAN III D. Directions to MOL contractors should be issued on Tuesday morning, June 10, at which time we will also notify the Congress and make a public statement that MOL is cancelled."

Overnight, Crews was no longer an astronaut. For the second time.

"The only reason we even had the MOL program was that a lot of people in the Air Force were very upset that the X-20 Dyna-Soar was canceled," Crews explained. "That was a very bad thing to have happened. Dyna-Soar was definitely forward progress."

"The Manned Orbiting Laboratory was just a stop-gap. People who wanted an Air Force program jumped at it, just to have something going; otherwise, they wouldn't have had anything. They knew that the only way they would ever use it [MOL] was if the unmanned systems did not progress as well as they needed it to … to do the job that we could do."

At the time of its cancellation, MOL directly employed 19,000 individuals, with an additional 65,000 contractors supporting the program. More than $1.3 billion had been invested (about $9.1 billion in 2020 dollars), yet save for a Gemini-B "pathfinder" engineering mock-up and several large mirrors, not a single piece of MOL flight hardware was ever completed. All of the intricately fabricated laboratory segments were apparently scrapped.

Shortly after MOL's cancellation, NASA accepted the younger MOL astronauts, those under 35 years old, as part of its astronaut corps. Crews was 40.

Crews remained in the Air Force for the time being, assigned to NASA's Aircraft Operations, eventually retiring with the rank of colonel in 1973. He helped evaluate the competing designs for the future space shuttle program while continuing to fly for NASA, as a civilian, until his retirement in 2000.

"NASA didn't have a space shuttle at that time [1969], nor any idea that they would get a shuttle. I had gotten so mad at the Air Force, I was offered to go back to Edwards but decided to go to NASA," recalled Crews. "I had a good working career at NASA. I enjoyed it very much."

Still, thinking back to that night when Armstrong walked on the moon, Crews watched more keenly than most, wondering about the intangible what-might-have-been.

"I came very close to applying to NASA for the second (astronaut) selection in 1962. That was when [Armstrong's] Dyna-Soar seat opened up, and I decided to take that instead," Crews explained. "However, if I had gone to NASA, I would have obviously been in the running for that Apollo flight."

- NASA's 17 Apollo Moon Missions in Pictures

- NASA's Space Shuttle Program in Pictures: A Tribute

- Timeline: 50 Years of Spaceflight

Roger Guillemette has been a Space.com correspondent since 2001, covering human spaceflight and military/intelligence space programs. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Special thanks to Dr. Dwayne Day, Dr. John Charles, Al Hallonquist, Boeing Images and Karen Gilbert of the National Reconnaissance Office for their assistance. Very special thanks to Col. Al Crews for his lifetime of service and for sharing his recollections.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Roger has been a Space.com correspondent since 2001, covering human spaceflight and military/intelligence space programs. He has witnessed close to 100 piloted spaceflight launches - from the July 1975 Saturn 1B launch of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project to the final launch of Shuttle Atlantis on STS-135 in July 2011. His live coverage of the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster was cited as a key factor in Space.com receiving the 2003 Online Journalism Award for Breaking News. Prior to joining Space.com, Roger was Editor/Producer and space reporter for Florida Today’s pioneering 'Space Online' website. He is a graduate of Roger Williams University and lives in Little Compton, Rhode Island.