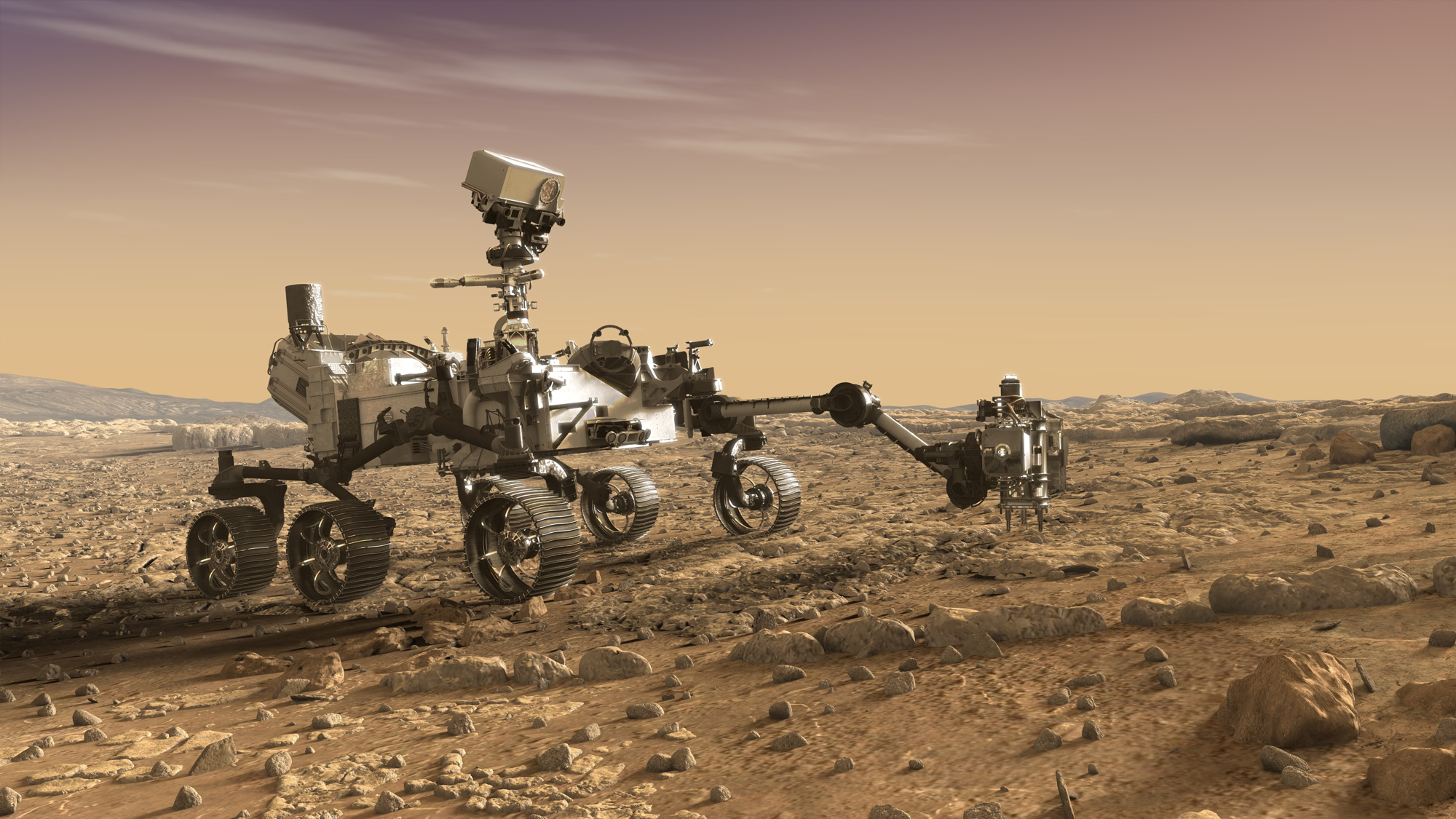

SAN FRANCISCO — Spotting signs of long-dead life is a tall order for a lonely robot on a faraway world, but NASA's next Mars rover should be up to the challenge, mission team members said.

NASA's 2020 Mars rover is scheduled to launch next summer and touch down in February 2021 inside the Red Planet's 28-mile-wide (45 kilometers) Jezero Crater, which scientists think hosted a lake and river delta in the ancient past.

The six-wheeled robot will then scour the area for potential biosignatures. This work will consist of observing Jezero rocks in fine textural detail and using several spectrometers to map geochemistry precisely onto that texture, Mars 2020 deputy project scientist Katie Stack Morgan told reporters today (Dec. 10) here at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

Related: NASA's Mars Rover 2020 Mission in Pictures

"It's our understanding of biosignatures in the rock record that it's that combination — texture and mapping of composition — that really allows you to build a strong case for a biosignature," said Stack Morgan, who's based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

"So, we are very much hoping that, with our payload, we can make a very strong case that there are biosignatures on the surface of Mars," should any exist, she added.

Stack Morgan passed around a fossil stromatolite that formed here on Earth to help illustrate her point. Stromatolites are mats formed by the growth of photosynthetic microbes known as cyanobacteria. This growth occurs in discrete layers, so mapping carbon-containing organic compounds precisely onto the layers in a similar Martian structure would provide strong evidence of life, she said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mars 2020 — which will receive a more memorable moniker soon, via a student naming contest — will be able to do such work. Its predecessor, NASA's Curiosity rover, cannot. Curiosity can image rocks in similar detail to Mars 2020, but it determines composition in bulk and therefore cannot map the geochemistry onto the observed structure.

"We would just grind up that stromatolite and tell you it has carbon," Curiosity mission scientist Ashwin Vasavada, also of JPL, said with a laugh during today's media roundtable.

That's no knock on Curiosity, which has been exploring Mars' 96-mile-wide (154 km) Gale Crater since August 2012 and is still going strong. Curiosity has achieved a great deal, finding, for example, that Gale supported a potentially habitable lake-and-stream system for long stretches in the ancient past. But the older rover isn't equipped with life-hunting gear.

Related: Long Window for Life on Mars: Hundreds of Millions of Years?

Mars 2020's on-site observations alone may not be enough to convince some researchers that life once existed on the Red Planet. Scientists are a skeptical bunch by nature, after all, and any announcement of a potential discovery of alien life will be scrutinized incredibly intensely, as we've already seen with the Viking Mars lander results and analyses of the Red Planet meteorite ALH84001.

But the mission is making accommodations for such skepticism. A core part of Mars 2020 is the collection and caching of 20 to 30 drilled samples for eventual return to Earth, where multiple research teams in well-equipped labs around the world can study the material.

The retrieval of those samples will be a joint effort of NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). Details of this plan are still being worked out, but Earth return does indeed seem like it's going to happen: ESA brass officially confirmed the agency's participation during a high-level meeting late last month. (ESA is working on its own life-hunting Mars rover, by the way, a robot named Rosalind Franklin, which is scheduled to launch next summer, just like Mars 2020. Rosalind Franklin is part of the ExoMars program, a collaboration between ESA and Russia's federal space agency, Roscosmos.)

Mars 2020 isn't just a life-hunting mission, however. The rover's analyses should also help scientists better understand the ways in which rocky planets evolve over time, Stack Morgan said. And Mars 2020 carries gear that should aid NASA's plan to put astronauts on the Red Planet in the 2030s.

For example, the coming rover is equipped with ground-penetrating radar, which will search for deposits of subsurface water ice — a key resource for Mars pioneers — and pockets of briny liquid, among other things. Another instrument is a technology demonstration that will generate oxygen from the carbon-dioxide-dominated Martian atmosphere.

Overall, the car-size robot will tote seven science instruments and 23 cameras to the Red Planet. Mars 2020 will also sport a microphone to capture otherworldly sounds, and the probe will bring a tiny, technology-demonstrating helicopter scout as well.

- Mars 2020: The Red Planet's Next Rover

- Life on Mars: Exploration & Evidence

- Photos: Ancient Mars Lake Could Have Supported Life

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.