Astronauts bound for Mars should swing by Venus first, scientists say

The roads of human spaceflight all seem to lead to Mars. For decades now, it's been the logical next step after the moon.

But if you're an astronaut or a cosmonaut on your way to or from Mars, you might make a surprising pit stop along the way: Venus.

A flight to (or from) Mars can happen more quickly and cheaply if it "involves a Venus flyby on the way to or on the way home from Mars," Noam Izenberg, a planetary geologist at Johns Hopkins University, told Space.com.

Related: How will a human Mars base work? NASA's vision in images

Izenberg is one of a number of scientists and engineers advocating that a crewed mission to Mars also visit Venus. This group of researchers has drafted a white paper on the subject, to be submitted for peer review at Acta Astronautica. According to that paper, using Venus as a stepping stone to Mars isn't just one option — it's an essential part of a crewed Mars mission.

"Venus is how you get to Mars," Kirby Runyon, a planetary geomorphologist at Johns Hopkins University who's on the white paper team, told Space.com.

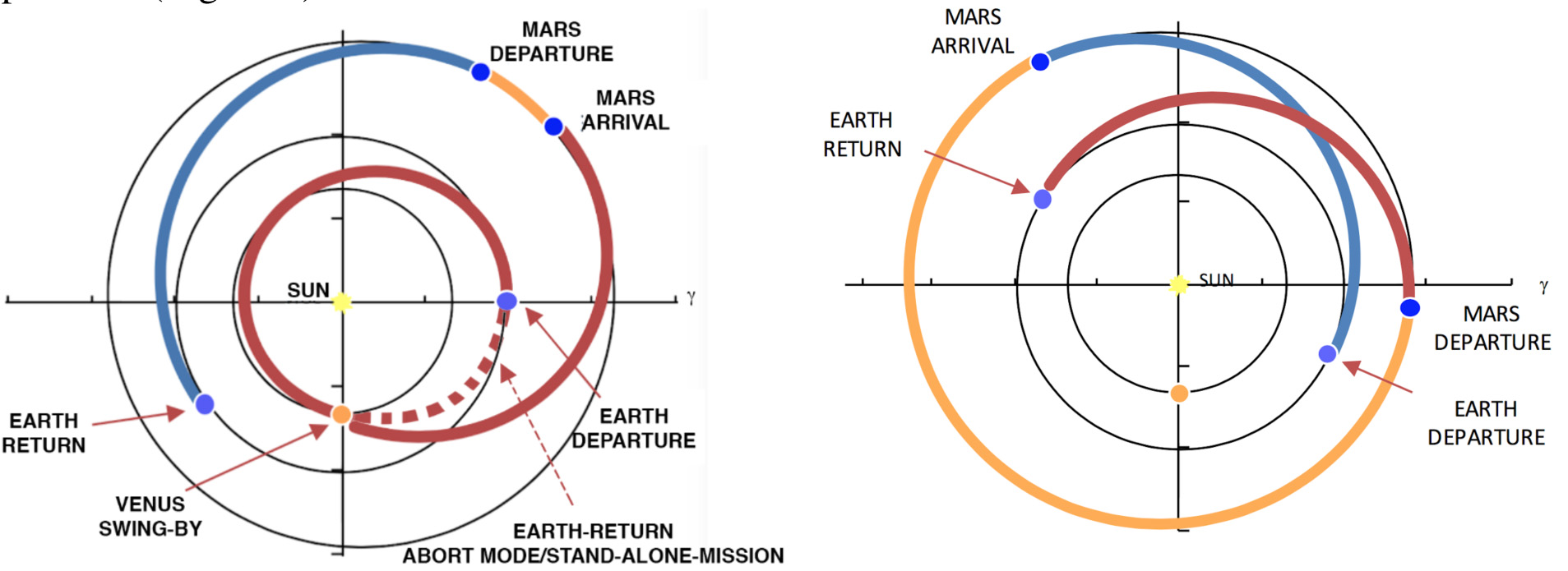

To get between Earth and Mars, there are two options. The first, and simplest, is a conjunction mission, in which a spacecraft flies between the two planets when they align in their orbits. After reaching Mars, astronauts would need to wait for the planets to align again before they could return to Earth. That wait could take as long as a year and a half.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The second option is an opposition mission, in which — either en route to Mars or on a return trip — a spacecraft would slingshot past Venus, using the planet's gravity to alter course. Using Venus for such a gravity assist would dramatically reduce the amount of energy needed for the trip, saving on fuel and weight, and therefore also on cost. This is the type of mission that these researchers support.

"It's preferable to fly by Venus for a gravity assist on the way to Mars," Paul Byrne, a planetary geologist at North Carolina State University, also on the white paper team, told Space.com.

A conjunction mission might look simpler on paper, but the opportunities for such transfers are few and far between. Mars and Earth's orbits only align to allow for a conjunction mission every 26 months. In contrast, you could theoretically launch an opposition mission every 19 months.

Furthermore, opposition missions allow for much shorter stays at Mars: astronauts could even go for trips as short as one month — as opposed to the year and a half a conjunction mission might take. While the actual amount of time that this flight might take could be longer, adding Venus to a Mars flight plan means that astronauts could return to Earth as much as a year sooner.

Additionally, in the event something were to go wrong during such a mission, going to Venus first also allows the possibility of quickly changing course and returning to Earth in a much shorter timeframe.

"You … greatly simplify the logistics of going to Mars, especially from the perspective of crew health," Runyon said.

But Izenberg and his colleagues aren't just treating Venus as a layover. They believe Venus would be a valuable destination.

"There's science at two planets for much less than the price of two separate crewed missions," Byrne said.

Robotic probes have captured an incredible amount of data through observations at Venus, but scientists think that visiting Venus with a crewed mission opens up new possibilities — especially if those visitors bring probes or rovers with them. "What humans can do better than robots is respond to observations on the fly," Martha Gilmore, a planetary geologist at Wesleyan University, who isn't involved with the white paper group, told Space.com.

Astronauts at Venus wouldn't have to deal with the lag — which could be anywhere between five minutes and 28 minutes — thanks to the time light takes to travel between Earth and Venus. Therefore, according to Runyon, "the crew would be able to control rovers on the surface and aircraft in the atmosphere in real time with a virtual reality headset and a joystick."

"If you do that with a purely robotic mission from Earth," Izenberg added, "you can't really do that easily."

The white paper team believes that piloting drones during such a flyby is more than just a dream. Runyon said that, if you look between the lines, the evidence is there that NASA is planning for an opposition-type mission. This NASA report released in April mentions "two-year Mars class missions" as a future goal.

"Assuming that this report is talking about normal forms of propulsion," said Runyon, "the only way you can get to Mars and back in two years is if you include a Venus flyby."

You can follow Rahul Rao on Twitter at @raorr108. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.