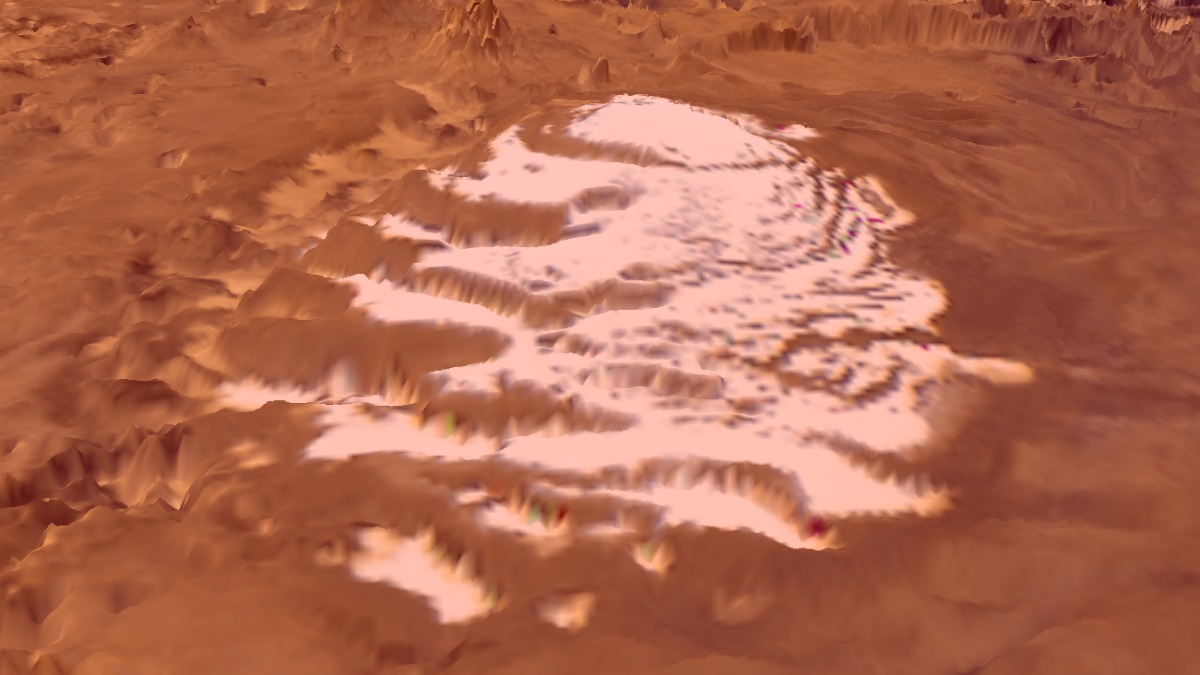

These dry ice glaciers on Mars are moving at its south pole

Fast-flowing ice is not unique to the Red Planet.

Carbon dioxide glaciers on Mars are fast-flowing phenomena.

A new study finds that dry ice flows closer to 100 times faster than water ice in the thin atmospheres on Mars, when on high slopes.

Researchers verified this process looking at carbon dioxide glaciers in the south polar region of Mars, and say modeling suggests this movement could have been going on for the past 600,000 years.

Studies like this have implications for understanding ice formation across the solar system. Earth, Mars and Pluto are verified locations for fast-flowing ice, but the non-profit Planetary Science Institute in Arizona stated this number likely will increase.

"Numerous types of ice exist in the solar system, and with the count of dwarf planets increasing, it's likely that some of them will have glaciers of carbon monoxide or methane, even more exotic than the dry ice glaciers just discovered on Mars," the institute said.

In photos: The search for water on Mars

The dry ice has increased both in volume and mass since it first formed more than half a billion years ago, although the process was periodically interrupted "by periods of mass loss through sublimation," lead author Isaac Smith, a PSI research scientist, said in the same statement. (Sublimation means the direct transformation of ice into gas.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

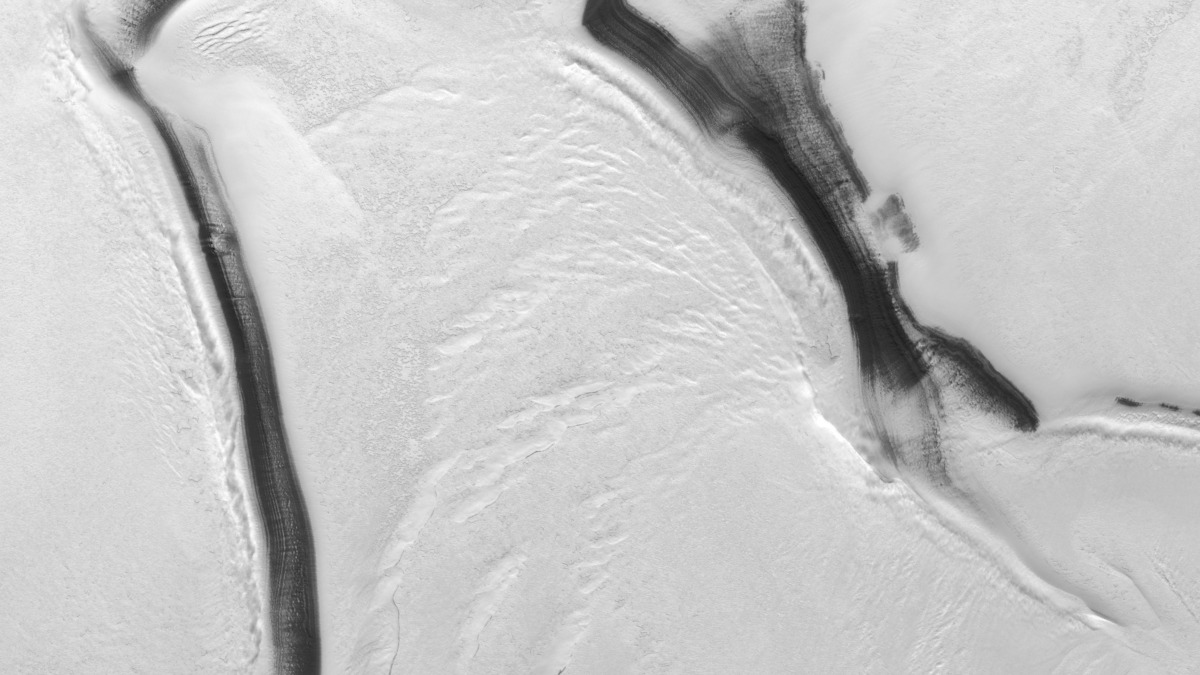

"If the ice had never flowed," Smith said, "then it would mostly be where it was originally deposited, and the thickest ice would only be about 45 meters [147 feet] thick. Instead, because it flowed downhill into basins and spiral troughs — curvilinear basins — where it ponded, it was able to form deposits reaching one kilometer [0.6 miles] thick."

Glacial modeling came from NASA's Ice Sheet and Sea-Level System Model, which was adapted to work on Mars from its current mandate to track evolution of the polar ice caps in Greenland and Antarctica. It showed glacial action is the dominant force behind the dry ice movements on Mars, as opposed to atmospheric deposition, which would more evenly spread the ice over a thinner depth.

"The ice is flowing downhill into basins, much like water flows downhill into lakes. Only glacial flow can explain the distribution," Smith said. While flow rate likely peaked 400,000 years ago when deposition was at its maximum, the slowly diminishing ice remains impressive in size. The longest glacier is about 25 by 124 miles (40 by 200 kilometers) long, Smith said, based on past research including PSI senior scientist Than Putzig.

The new study was published Tuesday (April 25) in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. Some of the work was verified with terrestrial glaciers, which have features such as compression ridges that were also spotted on Mars.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.