The 'doorway' seen on Mars is not for aliens. Here's how it really formed.

No, this is NOT a doorway for Martians.

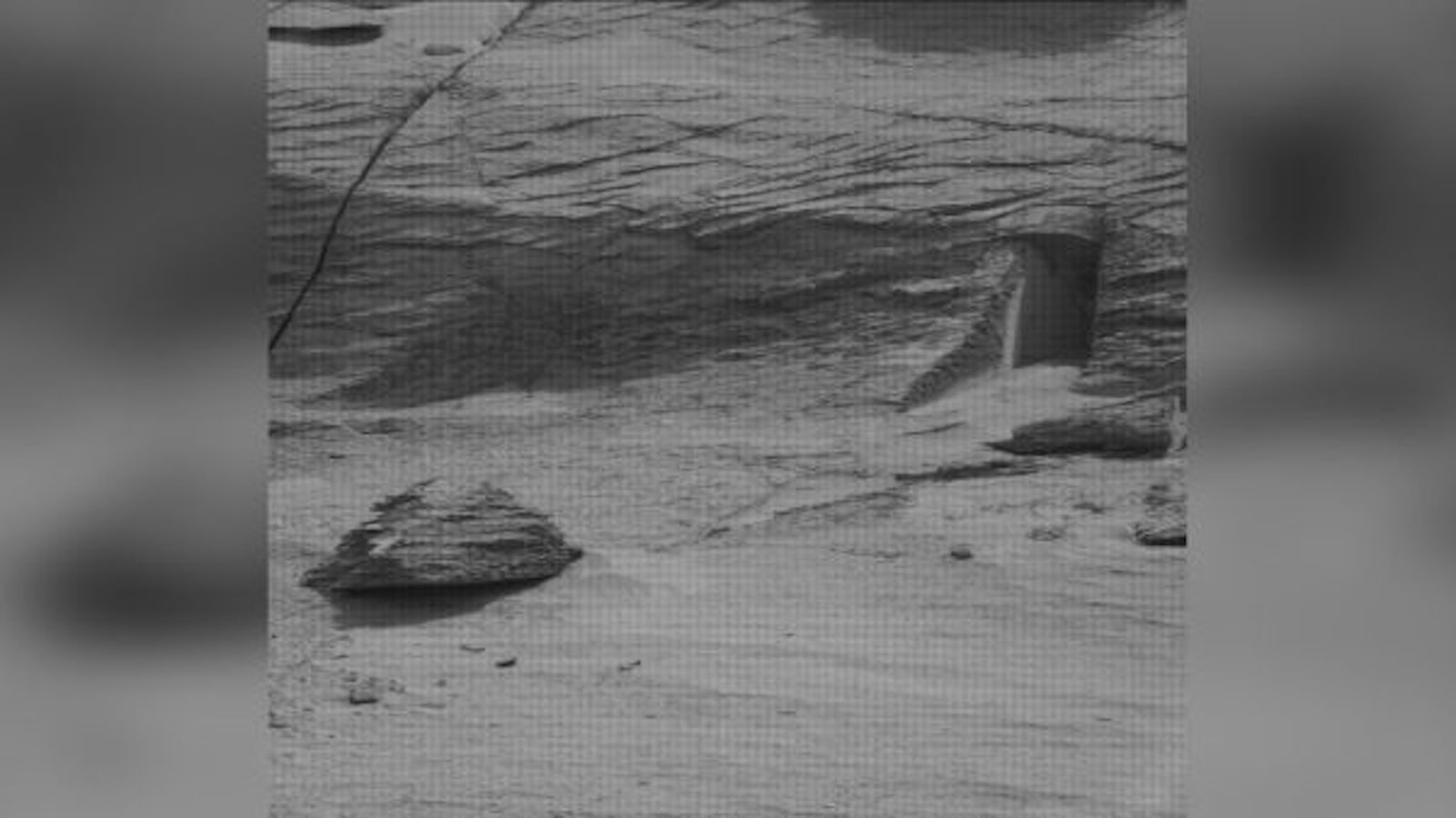

No, this is NOT a doorway for Martians. Although the internet erupted on Thursday after a photograph from NASA's Curiosity rover appeared to show an "alien door," experts are pretty sure it's just a natural feature of the Martian landscape.

"This is a very curious image," British geologist Neil Hodgson, who has studied the geology of Mars, told Live Science. "But in short – it looks like natural erosion to me."

Curiosity snapped the image with its Mast camera ("Mastcam" for short) on May 7, and it was released by NASA later in the week.

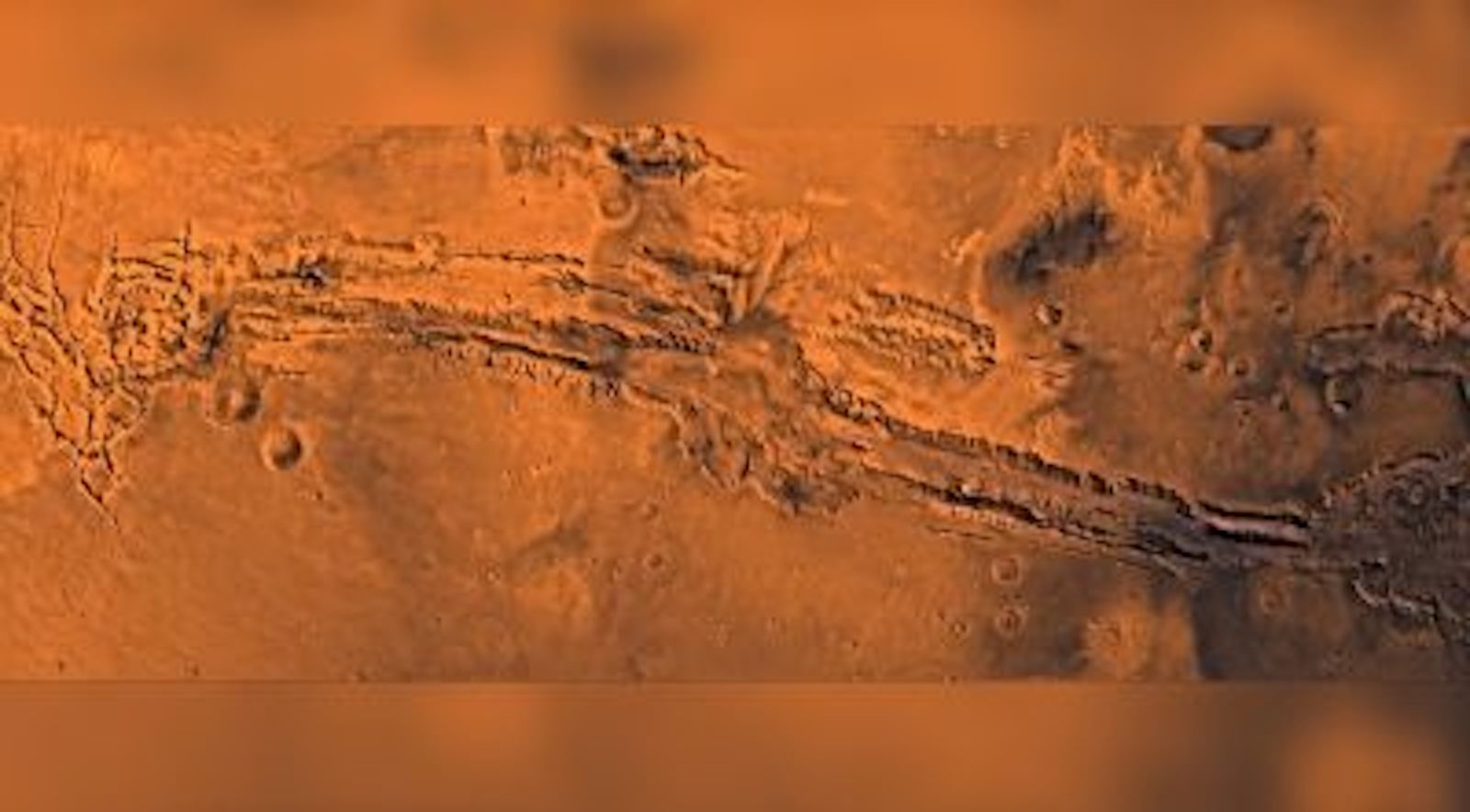

Several colorized images have been made from the original black-and-white one, including a panorama made by stitching several of Curiosity's photographs together, as seen on Gigapan.com, the website of a panoramic photography company.

Related: Seeing things on Mars: A history of Martian illusions

Several clues make it clear that the subject of the image is not an actual door: For a start, it's less than 3 feet (1 meters) high, planetary geologist Nicholas Mangold of the University of Nantes in France told Live Science in an email.

Or this may show the Martians were small, he quipped.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Other tongue-in-cheek suggestions from the internet included the idea that it is the space tomb of Jesus; a crib for E.T.; or a save-point for a video game, the Vice website reported.

But the real answer is that it's none of those things. Instead, what looks like a door is in fact a shallow opening in the rock that's almost certainly caused by natural forces, say the experts.

Mars erodes

So if the door isn't a door, what is it?

Hodgson, a vice president at the British geoscience firm Searcher, thinks the "door" is caused by erosion.

Rocky layers called strata can be seen on the rock, dipping on the left and higher at the right. "These are silt beds, with harder sandy beds that stand out," he told Live Science in an email.

"They were deposited perhaps 4 billion years ago under sedimentary conditions, possibly in a river (I'd need to see more of the outcrop to be sure) or a wind-blown dune."

Related: Is there water on Mars?

Martian winds have eroded the strata since they've become exposed on the surface, and the images even show traces of them inside the "door," he said.

Several natural vertical fractures are also visible in the image, among them fractures caused by the way rocks weather on Mars; and the small cave or "door" seems to have formed where the vertical fractures intersect with the strata, he said.

It seems "a large boulder has fallen out under its weight" to create the door-shaped cave, he said. "Gravity isn't as strong on Mars, but it is plenty strong enough to do this."

The culprit is the rock lying on the surface just to the right of the "door," which appears to have a smooth vertical edge – possibly because it fell out relatively recently and hasn't been exposed for long to the Martian winds: It's "all very natural, and similar to outcrops you can see in many arid places on Earth," he said.

No Marsquakes

Mangold, who studies geological data from the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers, agrees that the Martian "door" has been created naturally by the structure of the rock.

"These are fractures in two directions, creating an 'open box' with a door appearance – nothing artificial," Mangold said.

Internet speculation has raised the possibility that the small door-shaped cave may have been caused by a seismic "marsquake" – two of the largest Marsquakes ever recorded, for example, happened late in 2021.

But Mangold is cool on the idea: "The whole mountain is seriously fractured, there's no need of big marsquakes," he said. Instead, the fractures may have formed before the rock was exposed, by the hydraulic pressure of water in its cracks; or they may be a result of thermal stress caused by the seasonal variations in temperature on the planet's surface.

"It's a very beautiful fractured outcrop, indeed," said geologist Angelo Pio Rossi of Jacobs University in Bremen, Germany. Rossi has created panoramas of the outcrop from successive photographs from the Curiosity rover, and he too thinks the door-shaped cave was produced by the visible fractures in the rock.

Part of his work is to find analogs on Earth for geological structures seen on Mars, and there are numerous similar structures here on our own planet, he said.

And marsquakes probably had little to do with it: "Any block that is isolated by fractures can eventually fall downslope, even if the slope is gentle," Rossi told Live Science in an email. "The fractures themselves are not created directly by marsquakes, but simply by deformation through geologic time," he said.

Hodgson adds that the image illustrates how useful photographs from the Mars rovers can be: "This is a really good image … it just shows what good geology we can do with the images that come back from Curiosity and Perseverance."

Originally published on Live Science.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to correct the spelling of Neil Hodgson's last name.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.