Human artifacts abandoned on Mars should be cataloged to track our migration beyond Earth

"Homo sapiens are currently undergoing a dispersal, which first started out of Africa, reached other continents, and has now begun in off-world environments."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Scientists are calling for the cataloging of human artifacts left on Mars — from spacecraft and landers to rovers, probes, and other debris — to document humanity’s earliest steps in interplanetary exploration.

“Our main argument is that Homo sapiens are currently undergoing a dispersal, which first started out of Africa, reached other continents, and has now begun in off-world environments,” said University of Kansas anthropologist Justin Holcomb in a press release.

Holcomb and his colleagues argue that humanity is currently undergoing an “inaugural historical phase” in our migration across the solar system.

“We've started peopling the solar system,” he said. “And just like we use artifacts and features to track our movement, evolution, and history on Earth, we can do that in outer space by following probes, satellites, landers, and various materials left behind.

"There's a material footprint to this dispersal.”

Mars: The next phase in human dispersal

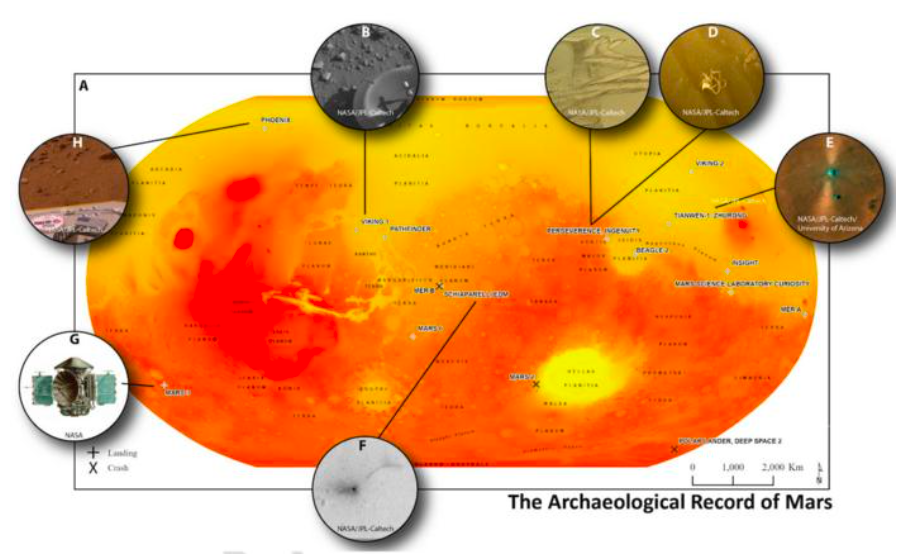

Mars, as our closest planetary neighbor, has been a primary focus of humanity's off-world exploration. Researchers estimate that, as of 2022, around 22,000 pounds (9,979 kg) of human-made debris is now scattered across the Martian surface.

"Since 1971, at least sixteen missions have contributed to the development of the archaeological record of Mars," the team wrote in their paper published in Nature Astronomy. "Archaeological sites on the Red Planet include landing and crash sites, which are associated with artifacts including probes, landers, rovers, and a variety of debris discarded during landing, such as netting, parachutes, pieces of the aluminum wheels (for example, from the Curiosity rover), thermal protection blankets and shielding."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Key historical sites include the USSR’s Mars 2 lander and PrOP-M rover, which became one of the first human-made artifacts to reach another planetary surface — though it ceased operating just ten seconds after its hard landing. The American Viking 1 lander, the first to successfully operate on Mars, and Ingenuity, the first autonomous helicopter to fly on another planet, also represent significant milestones in interplanetary exploration.

The scientific community has labeled much of this debris "space trash," but Holcomb argues that these materials hold significant archaeological and environmental value. He emphasizes that future missions should take care to avoid damaging the archaeological remains already present at these locations.

"These are the first material records of our presence, and that's important to us," he said. "I've seen a lot of scientists referring to this material as space trash, galactic litter. Our argument is that it's not trash; it's actually really important. It's critical to shift that narrative towards heritage because the solution to trash is removal, but the solution to heritage is preservation.

"There's a big difference."

Another element to consider is that while anthropologists have a solid understanding of how climate and geology contribute to the degradation of artifacts on Earth, the extreme and unfamiliar environments of planets like Mars pose new challenges.

Martian artifacts are exposed to cosmic radiation, solar winds, and interactions with water, soil, and ice, but how these forces affect materials over time remains largely unknown.

“Planetary geoarchaeology is a future field for sure, and we need to consider the materials not only on Mars in general but also in various places on Mars, which have different processes,” said Holcomb. “For example, Mars has a cryosphere in the northern and southern latitudes, so ice action there will increase the alteration of materials much more rapidly."

The scientist added that with Mars’ iron-rich sands, researchers want to know what happens when materials get buried on the Red Planet.

"The most obvious issue is burial by large dune sands. Mars has global dust storms, which are unique," Holcomb explained. "A single storm can literally travel across the entire globe. On top of that, there are local dust storms. The Spirit Rover, for example, is right next to an encroaching dune field that will eventually bury it. Once it's buried, it becomes very difficult to relocate."

Holcomb added that a step in the right direction is establishing a way to track and catalog human-made materials on Mars and other planets humans might explore.

"These artifacts are very much like hand axes in East Africa or Clovis points in America," he concluded. "They represent the first presence, and from an archaeological perspective, they are key points in our historical timeline of migration."

A chemist turned science writer, Victoria Corless completed her Ph.D. in organic synthesis at the University of Toronto and, ever the cliché, realized lab work was not something she wanted to do for the rest of her days. After dabbling in science writing and a brief stint as a medical writer, Victoria joined Wiley’s Advanced Science News where she works as an editor and writer. On the side, she freelances for various outlets, including Research2Reality and Chemistry World.