Want to learn how to survive on Mars? Look to Antarctica.

One is blinding white and the other a dull, dusty red. But both are cold, barren worlds, difficult to reach and full of tantalizing scientific mysteries.

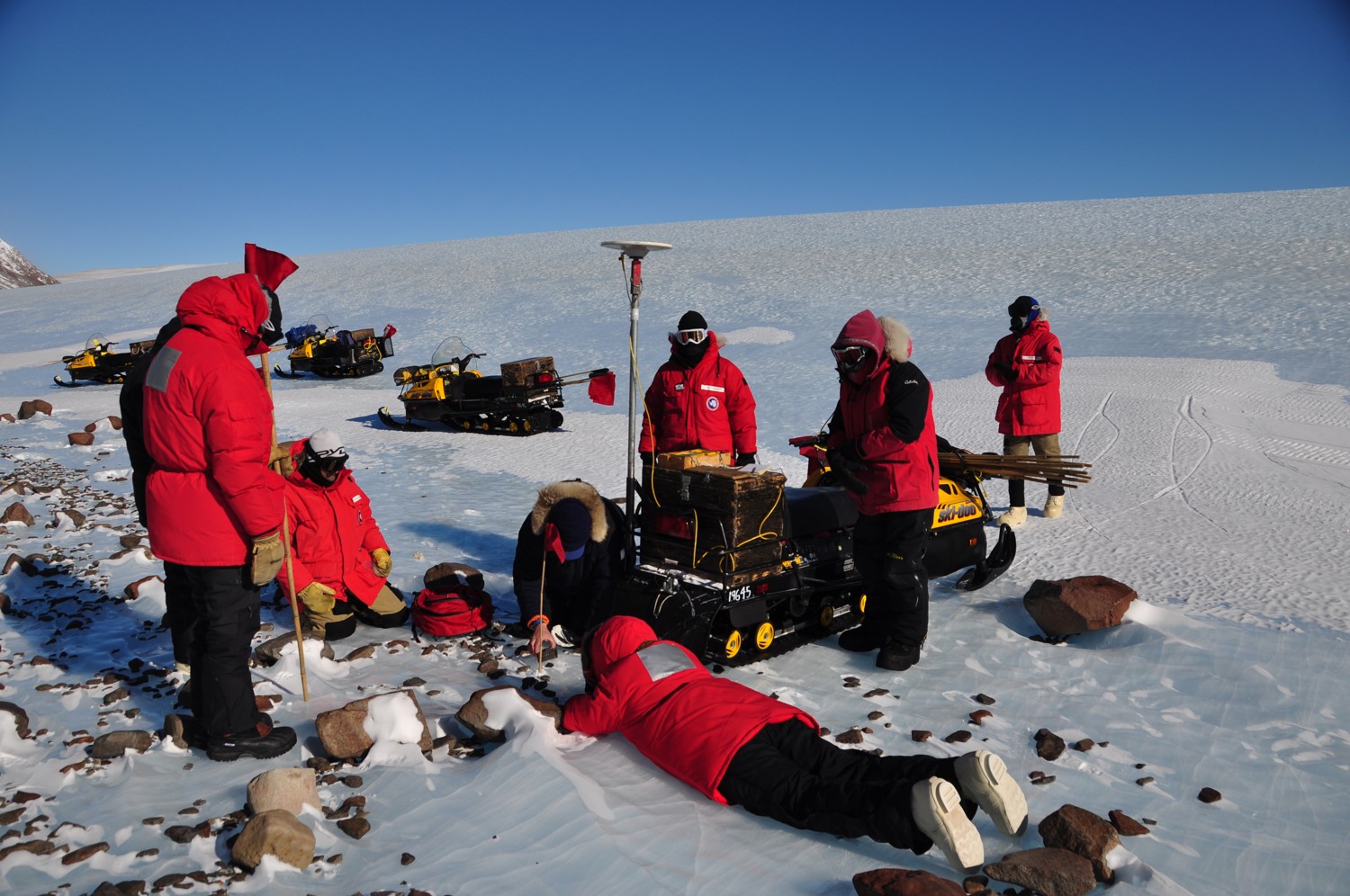

And lessons from the first world, Antarctica, may be vital for those who want to be the first humans on the second, Mars, according to Stan Love, a former NASA astronaut who now supports the agency's astronaut office. Those lessons, Love said in a meeting last month, stem from a decades-long U.S. government-funded program to search for atmospherically toasted space rocks on the brilliant ice of Antarctica.

"I'm going to talk about the Antarctic Search for Meteorites, which I think is the best analog we have on Earth for what it's going to look like to do field work on another planet," Love said May 20 in a virtual meeting of the Committee on Space Research focused on human missions to Mars. "So as I go forward, please be thinking what you're seeing is not on Earth but on Mars."

Related: Astronaut on ice: A search for Antarctic meteorites

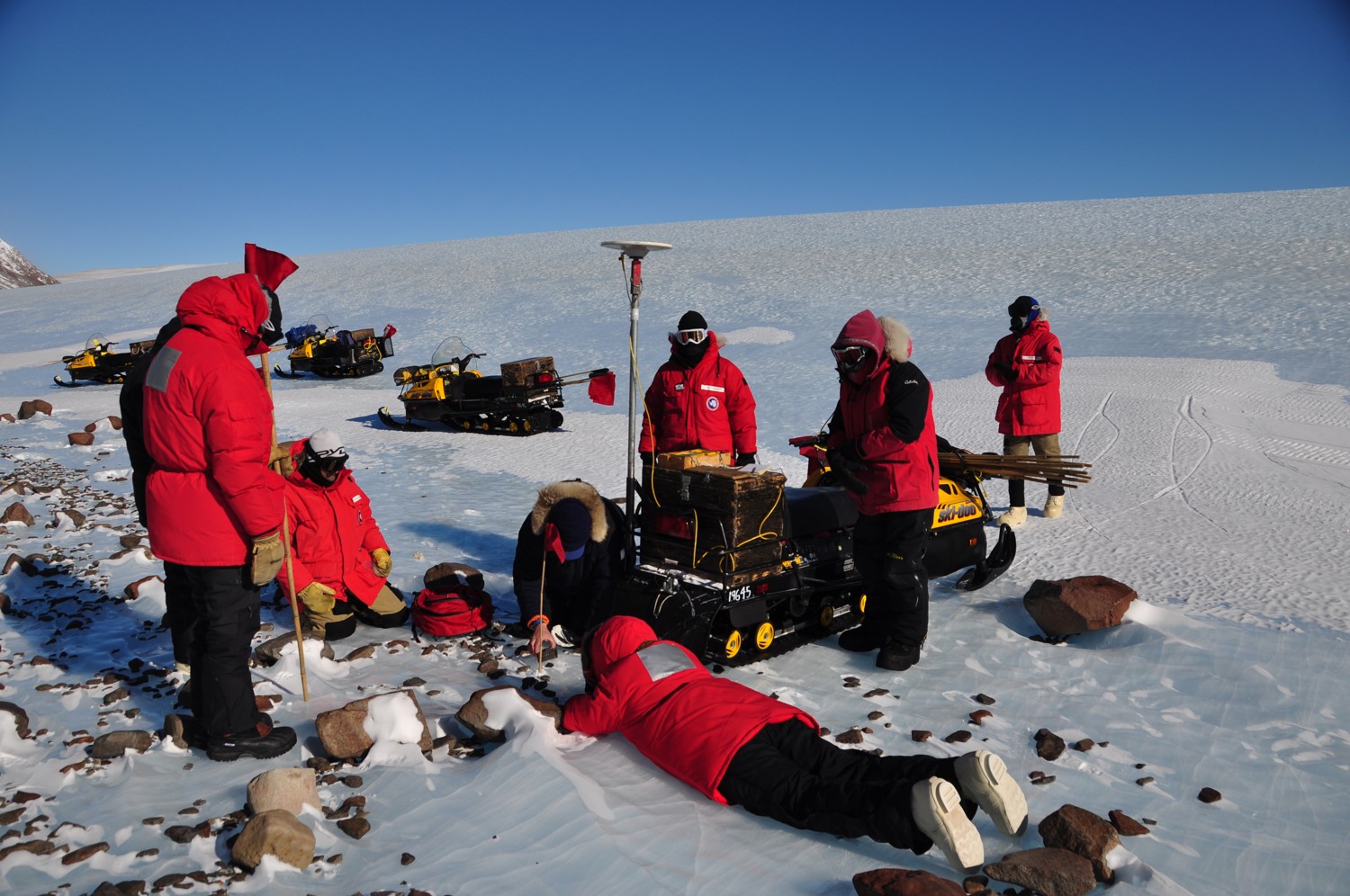

A key piece of the imagination exercise is recasting the bright red parkas that are standard Antarctic fare. "Every time you see a person in a red parka, I want you to think, that is a spacesuit," Love said.

In Antarctica, individual trips outside risk letting out some precious heat, and require about 30 minutes total to layer up remove them. On Mars, opening the door costs not just time and heat, but also risks the safety of the habitat and of the surface, since contamination between terrestrial and Martian systems could harm both science and human health. Leaving and reentering a habitat means two opportunities for material to sneak through.

"We can keep that as low as possible, but it's not going to be zero," Love said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The premise, of course, is that Martian science, like Antarctic science, would be worth some risks, as long as cautionary measures are in place. Antarctic expeditions to collect meteorites have yielded 50,000 such space rocks, which is why programs like the U.S. Antarctic Search for Meteorites that Love described operate.

But while these missions yield incredible science, it's not glamorous work, and a Martian expedition wouldn't be either. The parallels begin with transportation: a long, cramped journey aboard a transport vehicle packed with supplies, followed by an arrival that isn't actually the end of the road. The airfields servicing McMurdo Station, the U.S. scientific hub of Antarctica, are a drive away from the station proper. Love expects the same arrangement on Mars.

"When we go to Mars, people are going to land in a rocket and if there's an established station, they're not going to land that rocket on the station," Love said. "You'll have to take transportation from the rocket landing site to the city because we don't put the city right on the rocket landing site for safety reasons."

Participants in the Antarctic Search for Meteorites look for space rocks on the polar ice during the 2014-2015 expedition.

A view of McMurdo Station in Antarctica.

Scientists assign a sample number to a relatively large meteorite found during the 2014-2015 season.

Home base

Finally, though, the meteorite hunters arrive at McMurdo Station, a vision Love thinks may give future Mars travelers deja vu. "What might a settlement on Mars look like in, say, 100 years or settlement on the moon in 50 years?" Love said. "I think it's going to look a lot like McMurdo Station."

But McMurdo itself in its haphazardness looks a lot like another terrestrial predecessor, he added.

"They sort of put each building where they thought it might be a good idea to at the time, and there's not much of a grand plan to the station," Love said. "It really looks a lot like a mining town on Earth."

A mining town, that is, with a deep, obsessive passion for recycling, that is. "When you are ready to throw something away in Antarctica, you don't just throw in the trash can," Love said. Instead, a trash station features a dozen different carefully marked receptacles for visitors to sort waste into. And if you let chaos into the trash system, it will continue into the social system at the base. "If you just put everything in the non-recyclable there in the foreground, people will see you and speak sternly to you."

One key parallel Love expects to see between McMurdo and a future Mars base is the way square footage is allocated. Buildings make up just one quarter of the area of McMurdo, he said, whereas the rest goes to storing fuel, garbage and the like. A Mars exploration outpost would need an equally steep ratio, Love said.

And storage is already a problem on the space station, he said. "We allocated maybe 10% of the volume to stowage," Love said. Ever since, astronauts have struggled with where to put things, even after modifications increased storage space somewhat, he said. "If you're ever designing a space habitat, make sure you allocate half to three quarters of the total area to storing stuff, especially if your resupplies are coming only a year apart."

When it comes to what stuff needs to be stored, planetary missions come with a toll that space station missions don't carry: the cost of getting around on the surface. In Antarctica, powering the vehicles that scientists ride into the field takes up a huge portion of the fuel supplies the team brings to the continent.

"Electronics use only about a tenth as much as heating and cooking which in turn use only about a tenth as much as the amount of energy you need just to get around your field side," Love said. "So whatever we're doing on Mars, the vast majority of the energy we're going to have to bring and have available for use in camp is going to go for transportation around the field site."

Because, after all, the point of going to Antarctica isn't to visit McMurdo. McMurdo is a necessity; the real destination is out on the ice.

Field work

In the case of the Antarctic Search for Meteorites, the ice is crucial; it's what makes the southern continent a worthwhile place to hunt for space rocks. After all, atop solid ice sheets, there aren't many terrestrial rocks nearby to dilute the skyfall, and the burnt fusion crust of meteorites stands out against the brilliant ice.

So out onto the ice scientists go, flying out from McMurdo and setting up a makeshift tent camp for fieldwork.

But for meteorite hunters in Antarctica, snowmobiles are nearly as vital as the tents themselves, Love said, since they facilitate the science. Even if protective gear doesn't interfere too much with an explorer's ability to walk around, he said, the terrain within, say, a 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) range of a camp can't keep a team occupied for long.

"You'd end up doing all the work you could and finding every interesting rock there is in a kilometer very quickly, and then you're just sort of playing cards," Love said of what an expedition without snowmobiles would be like. "Whatever we're going to do on Mars, if we don't want to finish up in a day and just play cards for the rest of the time, we're going to need that surface mobility to open up more areas to do our interesting scientific work."

But Mars missions will have their unique aspects from Antarctic missions as well. In particular, Martian teams will likely conduct more sample analysis in the field than Antarctic teams do, Love said.

"We do not do any science on meteorites in the field in Antarctica, because it is too dang cold. Somebody in a nice warm laboratory can look at that rock," he said. "On Mars, since we're going to have more time, we will probably do a little bit more work." Mars samples will also be expensive enough to bring home that expeditions will want to be sure to do enough initial work on-site to be confident they are returning the very most interesting samples for terrestrial labs to study.

But perhaps the most valuable lesson from McMurdo for would-be Mars explorers is the importance of time management. Staying alive in hostile environments, it turns out, is a time-consuming endeavor.

That was clear when Love analyzed the way the team used time throughout their visit to Antarctica. "Only about half the time we spent away from home did we actually spend doing the field work," Love said. "The rest of it was getting places and managing stuff. So whatever we do on Mars, we are going to be spending a great deal of time just with the basics of life and handling our gear, probably more than we expect. Less of that time will be spent actually prospecting, looking for life, doing whatever it is that we're going to do on Mars."

- Photo: Dazzling aurora appears over Antarctic station

- The decade of Mars: How the 2020s may be a new era of Red Planet exploration

- Antarctica and the Big Bang: Science at the world's bottom

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.