Ready to pack your bags and hit the cosmic highway for a new off-world home? The folks at ABIBOO Studio and SONet are putting out the welcome mat and presenting their vision for what might become the first capital city on Mars, housing up to 250,000 residents.

The city, called Nüwa, was brilliantly conceived by ABIBOO and SONet, a scientific think tank headed by astrophysicist Guillem Anglada, who led the discovery of exoplanet Proxima b. It's a visionary concept for a completely scalable, sustainable Red Planet metropolis carved into the 3,000-foot (1,000 meters) cliff face of Tempe Mensa, and was selected as a finalist by The Mars Society's 2020 contest for feasible settlement designs.

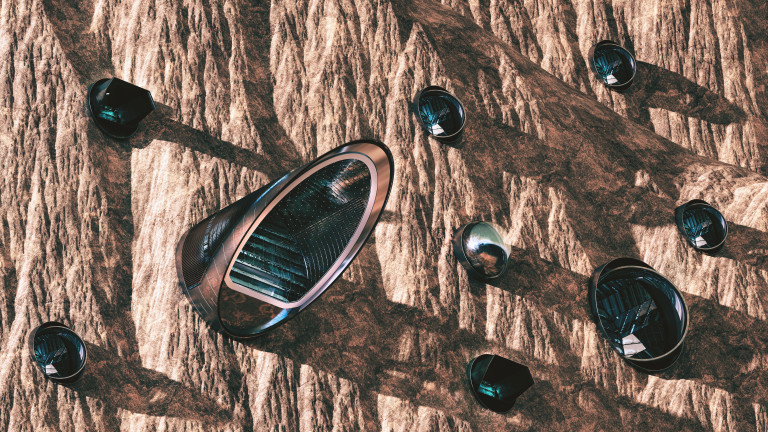

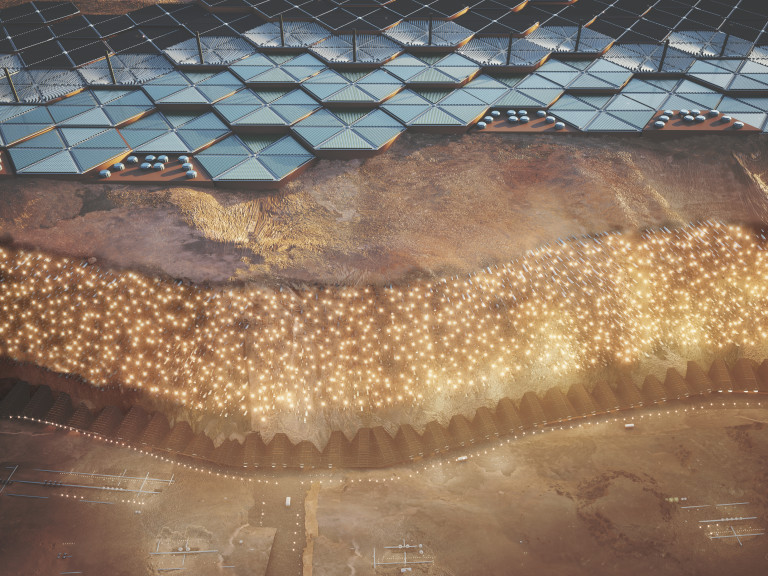

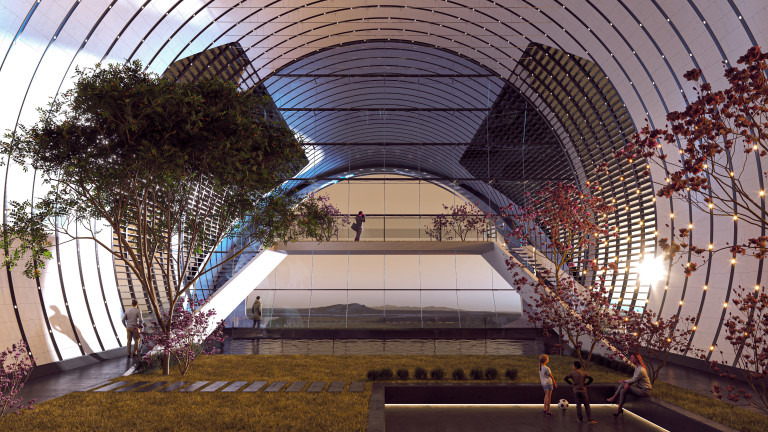

ABIBOO founder and chief architect Alfredo Munoz and his team created the comprehensive design work and its stunning digital artwork, including urban parks and hydroponic gardens, that have Earthlings yearning for a one-way ticket to this large-scale Martian community.

The ABIBOO team thinks construction could begin as early as 2054 and welcome the first wave of colonists by 2100.

According to their official report, the design includes five cities, with Nüwa as the capital and each city hosting 200,000 to 250,000 people. The rest of the settlements mirror the urban strategy. For example, Abalos City would be located at Mars' north pole to leverage ice access, and Marineris City would be in Valles Marineris, one of the biggest canyons in the solar system.

Space.com spoke with internationally known architect Alfredo Munoz about his involvement in the Nüwa city project, his enthusiasm for its modular blueprints, why he believes it's a global construction enterprise for the ages, what the team's imaginative influences were in its conception and more.

Space.com: What's your role in this ambitious project, and what excites you most about its potential?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Alfredo Munoz: I'm the founder of ABIBOO Studio, which is an international architectural firm. But I'm also on the board of directors of SONet, a multidisciplinary group with experts in different fields in the space industry. We were interested in using the group to provide solutions for sustainable innovations in an outer space settlement. Together, we designed the Nüwa city project, which we believed could be the first sustainable city on Mars.

Space.com: How did you approach the aesthetic and logistical concerns for Nüwa city?

Munoz: I think it was a combination of factors. First, it was the vision and the challenge that The Mars Society contest proposed. Coming up with a permanent settlement for 1 million people was the core of the stratification for the city. Up until now, there have been other solutions for settlements on Mars, but nothing like this. The challenge for a small amount of people to live temporarily on Mars is a completely different strategy from a design point of view than coming up with a city that must improve the lives of people who are born and live and die in the city.

From a design aspect, Nüwa was created by top scientists in a variety of fields. That gives the project a strong confidence that the design is valid and feasible. It's not just about beautiful images and beautiful architectural solutions. It's got experts behind it, and it was innovative in the way we solved so many of the challenges we'll face while setting up a Mars settlement. We did it in a very scalable manner, creating spaces that will be potentially exciting and beautiful. Architecture is not always about solving problems; it's about creating art.

That combination is what myself and the team on this project were able to bring. The marriage between strong technical and scientific solutions, along with innovative architectural ideas, as well as The Mars Society's vision, has created the amount of new interest in society saying that this is really possible. Why not be optimistic with a permanent city on Mars?

With urban planning projects, we often face issues where we need to create identity. How can we create environments that are attractive for people so it creates a sense of identity and belonging? It goes beyond beauty. It's about the emotional well-being of the people that are going to enjoy and live in that space. That was critical for us and something we wanted to do from the very beginning.

Space.com: What does the chosen name "Nüwa" mean?

Munoz: Nüwa comes from Chinese mythology. There was a goddess that created the universe and protected humans from all the bad things that happen, and her name was Nüwa. So when we were talking to SONet about potential names, we thought it was a fantastic representation — not only of what the name means, but also how we envision Nüwa as a multicultural location.

Most of the team is from Europe and the United States, but we thought to bring in Asian culture and Asian background that compensated for that lack of Asian aspects on the team. Again, we envision Nüwa city as a completely inclusive city with people coming from all backgrounds, and we thought this was a beautiful opportunity on both fronts. We really want this to be global.

Space.com: What were some of your influences in creating this Mars megacity?

Munoz: It's funny; we really didn't look at science fiction when we were trying to solve the problems we have on Mars. Consciously, there's always some influence from things like "Blade Runner," and that movie had a very big impact on architects in my generation.

In my case, it was more of my experience with Toyo Ito. He's one of the most influential architects alive. He was granted the prestigious Pritzker [Architecture] Prize in 2013, which is the equivalent of the Nobel Prize, and he's the architect I worked with years ago in Japan. He gives a lot of importance to systems that can be replicated in a very conceptually easy manner.

So when I approached this with the rest of the team, it was very important to come up with something that was simple, scalable and able to generate an identity. We never really went back to science fiction. We were trying to do engineering and architecture. Sometimes, when you look at references that are visually too appealing, you can let go of that anchor of science.

Space.com: Besides the challenges of creating enough breathable air and tunneling technologies, what are other obstacles that need to evolve for Nüwa to be born?

Munoz: Yes, there are some critical parts that we've identified that exist ahead, and until those parts are resolved, we won't be able to properly implement construction on a scale like Nüwa. The first one is the fact that we'll be relying on steel. Based on the scientists, it will be relatively easy to obtain steel from water and CO2, which can create carbon. We're basically building the entire city with local resources. We're barely bringing things from Earth, which is critical for that scalability and sustainability. We'll still need to test and develop that technology before going ahead.

Another challenge is that we will need on-the-ground confirmation from a geological point of view that the location conditions are appropriate, and that requires actual astronauts — the same way that here on Earth, we're not going to perforate the mountain without doing the proper site analysis. A lot can be done with robotics, but some astronauts will need to be there.

The use of artificial intelligence and robotics will also be critical. The way the robotics industry is going, in more than 20 years, we'll be more than ready to have the know-how to start construction. But even if the city is ready to be built, we still need to bring the population to actually live there.

One of the biggest hurdles we found is that, due to the two-year window of opportunity, [planetary alignment for most efficient transit time to Mars] the amount of rockets required to send 250,000 people from Earth to Mars will be huge. Even if [SpaceX CEO] Elon Musk is doing great work and will be able to send humans to Mars very soon, the volume needed is completely mind-blowing. Our engineers are working on ideas of how we can scale that component up. We are hopeful that in the next 30 years, we'll get to the point where those critical parts are resolved so we can start implementing a construction like Nüwa on Mars.

Space.com: It's difficult to put a price tag on such a monumental endeavor, but what would you speculate as the costs for Nüwa?

Munoz: We were basically comparing it to what the Panama Canal cost back in time. We're talking about a large infrastructure that takes decades to build and requires a lot of commitment. The impact it can have concerning well-being and commerce can be staggering.

We still have no detailed analysis of cost. It's a primary process, and we're working on trying to build prototypes and getting the right partners and financing to continue moving forward. We have a journey of many years ahead, and part of that journey will be doing a detailed breakdown of costs. If we solve some of these obstacles in the next 10 years, we'll have a much better idea.

If we compare it with 60 years ago, when Yuri Gagarin went into space, the amount of complexities involved for trying to send someone into orbit were staggering. In 60 years, which will be 2081, if we compare back in time how much humans have been able to develop technology, we could be in a position where we could speed up our timeline beyond what we're currently targeting. Sixty years is nothing.

Space.com: How do you hope your conceptual Martian city will stir the imaginations of future generations?

Munoz: I'm really passionate about education, and I've been involved in academia and teaching in the past. I think the role that education can have is huge. And architecture has a critical role in having either a positive or negative impact for future generations. To be able to create a plan and be part of the team that came up with a highly scalable solution that could be a road map for a permanent settlement on Mars, to come up with such a landmark in what being a human is and what society can become, is so enriching as a professional. It's fascinating.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeff Spry is an award-winning screenwriter and veteran freelance journalist covering TV, movies, video games, books, and comics. His work has appeared at SYFY Wire, Inverse, Collider, Bleeding Cool and elsewhere. Jeff lives in beautiful Bend, Oregon amid the ponderosa pines, classic muscle cars, a crypt of collector horror comics, and two loyal English Setters.