Robot 'Mole' on Mars Begins Digging Into Red Planet This Week

Update, 5:20 p.m. EST: The mole's deployment has been delayed by two days because the commands didn't reach InSight in time, according to a statement from the German space agency, a collaborator on the mission.

The first-ever interplanetary "mole" is about to start burrowing into the Martian surface — but this mole is purely mechanical, and it would flounder on any other world.

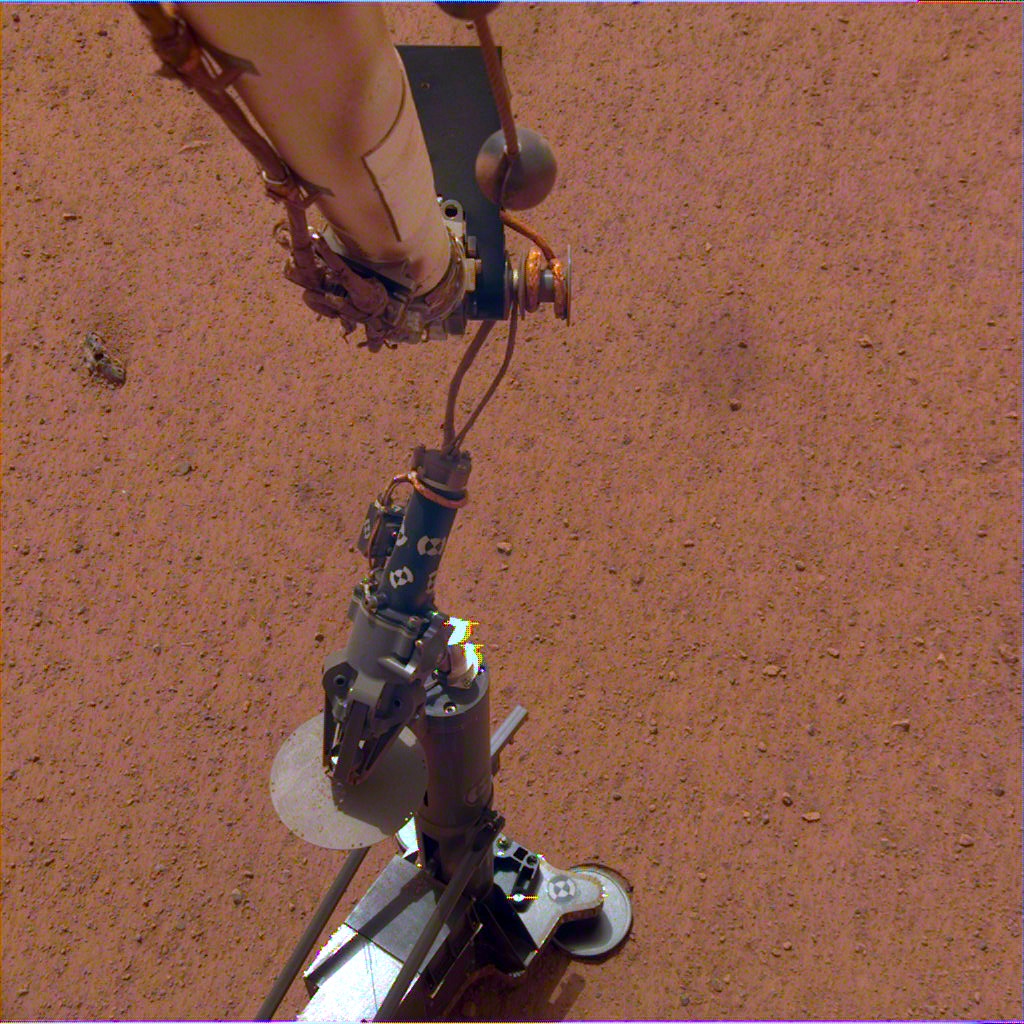

The mole is one of the key instruments incorporated in NASA's InSight mission, which landed on Mars in November and will begin its work in earnest tonight (Feb. 26). It will be the first robotic instrument to measure how heat flows through another planet — a crucial measurement that will help scientists understand how Mars got to be the way it is.

"Unlike, say, a camera, which we've flown hundreds on various missions, there hasn't been anything like the mole before," Troy Hudson, an instrument systems engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), told Space.com.

Related: Mars InSight in Photos: NASA's Mission to Probe Core of the Red Planet

InSight placed the mole — formally known as the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Probe — on the Martian surface two weeks ago. But the instrument itself has been in the works for about a decade, and scientists are raring to see what data it can gather.

"Getting the mole into the regolith and seeing how it behaves is also going to be exciting from an engineering standpoint, as well as from a science standpoint," Sue Smrekar, deputy principal investigator for the InSight mission and a geophysicist at JPL, told Space.com. "It's just going to be exciting to actually get under the subsurface."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The mole's nickname stems from the fact that it will hammer itself down through the Martian regolith, pushing aside dirt and rocks in order to reach — if all goes well — 16 feet (5 meters) deep. Dangling behind it will trail a cord packed with sensors.

As the mole itself digs, it will send pulses of heat into the surrounding rock, then measure how quickly the heat dissipates. That will tell scientists what the ratio of rock to air is in that specific patch of Mars, which is particularly interesting, since InSight sits within a large impact crater. "It'll help us understand, OK, Is this primarily sand that's been blown into this crater [or] is it more of a mix of things that you would expect from impact crater ejecta?" Smrekar said.

Once the mole drills as far as it can, it will settle in to measure temperature changes throughout the Martian year. That will let scientists trace how heat moves through the planet, independent of weather on the Martian surface — and that heat flow has important implications for understanding how Mars became Mars. "Heat is the engine that drives geology," Hudson said.

There are two main sources of heat within a planet like Mars, and both tell scientists about how the planet formed. "One is the initial heat from accretion — all these rocks are smashing together at enormous velocities, and so you have this initial heat budget," Smrekar said. (Scientists don't expect to find very much heat from this source on Mars.)

The second source is a time-release phenomenon scientists believe is strongest in the crust: radiogenic elements like uranium, thorium and potassium decaying and releasing heat. "That's what we're really expecting to learn the most about, is the concentration of these radiogenic elements," Smrekar said.

Once the researchers have pinned down those concentrations, as well as other characteristics of Mars that InSight is designed to measure, like the thickness of the planet's crust, they can feed those values into models that evaluate different scenarios describing how Mars became the way it is now. If all that seems a bit abstruse, consider that heat flow on Mars would affect when the planet's volcanic activity ceased and whether it's hiding liquid water below its surface.

All that science is reliant on an instrument that isn't particularly impressive in action, Hudson said, based on his experience watching terrestrial prototypes. "In all honesty, it's kind of boring to watch even when you can actually see it happening."

But the mole's unassuming appearance masks a huge amount of engineering work that went into the team's development of a new tool for planetary science. "We are literally breaking ground on a new type of investigation," Hudson said. Scientists have heat-flow measurements of the moon, but that data was gathered during the Apollo program, through the work of astronauts. "They did that all with complicated equipment and lots of elbow grease."

InSight couldn't rely on any such human help. Instead, Hudson and his colleagues had to tailor the instrument perfectly for the specific goals the mole needed to accomplish and the environment in which it would do so.

"It probably couldn't do its job as well, at least this particular design, on the moon," Hudson said. That's because lunar and Martian regolith are very different: the first has been pummeled by so many impacts that the mole wouldn't be able to worm its way down, pushing aside dirt and rocks. "[Lunar regolith] is like concrete, and if you push something into it, there's no pore space that you can fill up."

Scientists can't know the mole's odds of succeeding in advance because the major concern is that it might run into a boulder too large to work around — about 3 feet (1 meter) across. The deeper the mole gets, the more accurate a reading the team will be able to take of the planet's internal temperature flow, without interference from weather at its surface.

Once the mole's data is in hand, it will be up to the scientists to understand what it can tell us about our neighbor. "Maybe Mars will surprise us," Smrekar said. "That's always the most interesting result — when you get something you don't expect."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.