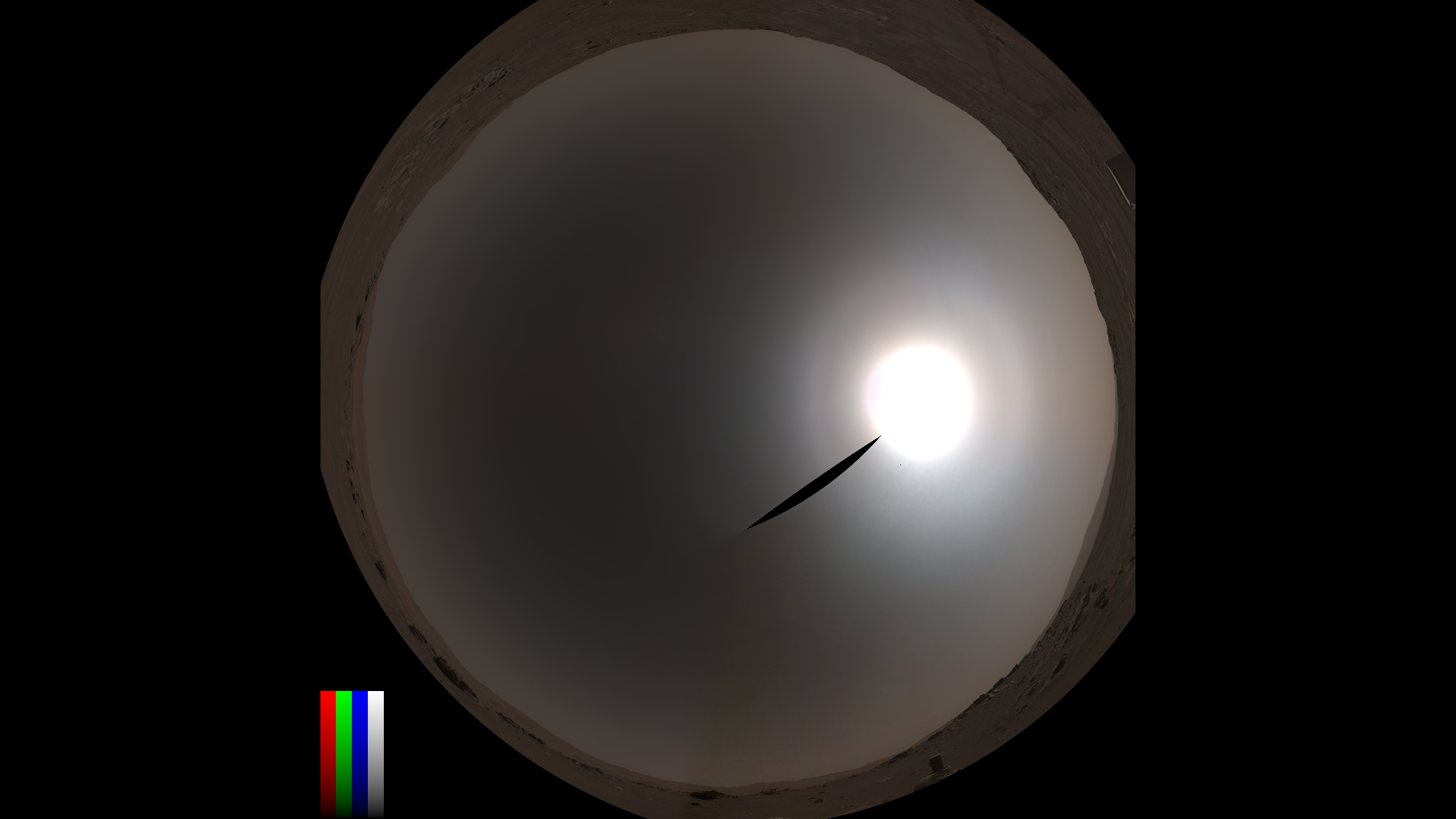

Sun halo on Mars! This Martian sky sight spotted by Perseverance rover was once thought to be impossible

NASA's Perseverance rover has spotted a phenomenon scientists had lost hope of ever seeing on Mars.

On Earth, when conditions are just right, ice crystals in the atmosphere can warp sunlight to create the appearance of a bright spot on either side of the sun, or of a halo ringing it. And scientists have long thought that a similar optical trick could occur on other planets as well. But despite decades of robotic explorers on the surface of Mars capturing countless thousands of photographs of the skies, scientists hadn't seen any sign of a sun halo.

Until Dec. 15, 2021, that is.

"Perseverance really surprised us with some of the images that we got back in December," Mark Lemmon, a planetary scientist at the Space Science Institute, a nonprofit research institute in Boulder, told Space.com.

"I've been involved with this for a long time, and we've looked for halos everywhere and in lots of images," he added. "I looked at that and I thought, 'I'm gonna have a hard time finding an explanation for this.' Because everything has been a false alarm, and that just looks so much like a halo that I thought it was going to be a lot of work to figure out what was really going on."

Related: 12 amazing photos from the Perseverance rover's 1st year on Mars

Ice in the sky

Even on Earth, it takes particular conditions for a halo to appear around the sun.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sunlight has to encounter pencil-like ice crystals swirling through Earth's atmosphere, usually in the form of wispy cirrus clouds very high up. The hexagonal structure of water-ice crystals dictates the size of the halo, at 22 degrees away from the sun, or about the width of two fists held at arms' length.

If the crystals are too small or the clouds are too thick or too warm, the sun is on its own — no halo. Crystals of other chemicals in the atmosphere can have a similar effect, but each chemical's crystal structure will create a halo of a distinctive size. "It's almost like a fingerprint that tells you what the element was, what the shape of the particle was, and then a little bit about the size," Lemmon said.

Carbon dioxide is much more plentiful in Mars' atmosphere than water is, so the team checked how large a halo crystals of dry ice would create, but that calculation didn't match what Perseverance had seen.

And neither did anything else Lemmon and his colleagues checked.

They investigated whether the camera itself might have created the bright ring, but the feature didn't match such artifacts in other images. Moreover, the strange photo was part of a sequence of five images Perseverance took panning across the sky; the sun and halo alike appeared in three, each time in a different spot in the frame.

And it definitely wasn't dust. "We've got a lot of pictures that show you what kind of features you get from dust in the sky, and we know for sure that you never get a halo from that," Lemmon, now the lead author on a paper describing the work, said. "There were really no other candidates."

Studying an alien atmosphere

Scientists have spent decades studying the Martian atmosphere, both as a way of understanding Mars and also as a way of understanding atmospheres more generally.

"Every planet that has an atmosphere is a laboratory for how atmospheres work," Lemmon said. "We can't understand something completely by looking at one example of it and then trying to figure out what it would be like if things were a little bit different."

And while the fleet of orbiters that has circled the Red Planet over the decades has excelled at gathering atmospheric data, scientists need more: a view from the surface. "Everything that we can learn about the atmosphere anywhere on Mars — looking at the clouds, looking at the dust storms, looking at dust devils — we have to validate how it plays out there on the surface, where the weather matters," Lemmon said.

That's why Perseverance, like Mars lander and rover missions before it, is equipped with a small weather station, and why scientists don't keep the rover's cameras resolutely pointed at the ground. Perseverance even carries SkyCam, a camera that only looks up and snaps images each Martian day, or sol; many photos from the rover's navigation camera also show a swath of sky. (NavCam snapped the image in which Lemmon identified the halo.)

And the presence of a halo around the sun does teach scientists about Mars' atmosphere, particularly that ice crystals can grow larger than any that scientists have measured directly. But with only one example in hand, Lemmon is hesitant to draw any sweeping conclusions.

"I think the most important thing for us is that we've learned that it is a thing that can happen," he said. "We need to look harder for it at Perseverance, at that site."

In particular, Lemmon is eager for the next time Mars enters the same season as the December 2021 observations, what scientists call aphelion cloud belt season, which will next roll around when Earth's Northern Hemisphere is in summer next year. "When it comes around again, we will spend the entire season looking for this and being ready to follow up and try to investigate in more detail if we see anything," Lemmon said.

The research is described in a paper published Sept. 3 in Geophysical Research Letters.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.