Radiation poses major obstacle to future deep-space astronauts bound for Mars

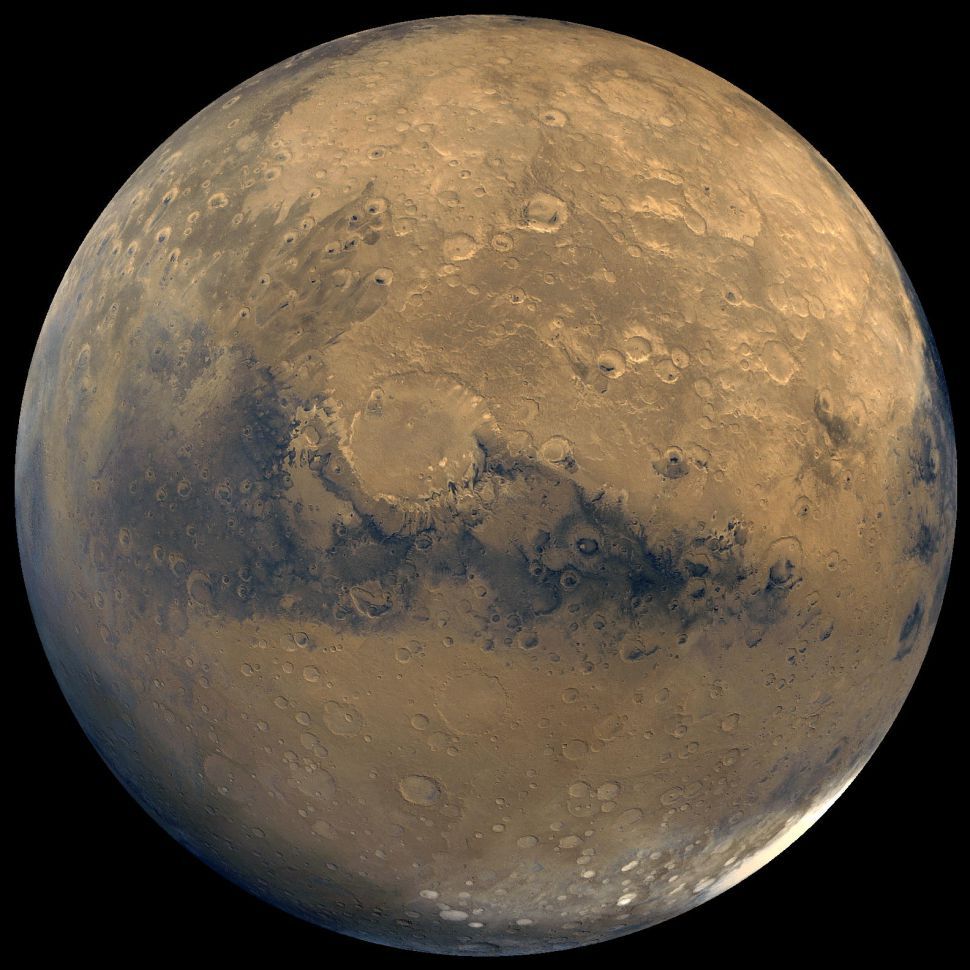

A roundtrip from Earth to Mars, plus time on the Red Planet, would mean a human crew could spend months or years in deep space.

Mars seems to be on everybody's mind in the space industry. There are already several robotic missions to the Red Planet underway, and companies and space agencies are already working to one day send humans there.

But a crewed mission would present many more challenges. One of these obstacles is radiation, and so researchers are working to find a way to protect a crew against the dangerous radiation of deep space.

Humans evolved underneath the protective blanket that is the Earth's atmosphere and magnetosphere. Our bodies are not like the robots we shoot into the far reaches of the solar system. We are made of organic matter that needs to be shielded from harmful radiation.

Related: Mars Explorers Will Tackle Radiation, Depression … and Space Bread

Radiation comes from waves of energy. There is radiation around us all the time — even bananas, which are rich in potassium, emit radiation — but the amount of radiation we're exposed to on a regular basis is so low that our body copes fine with it. However, some waves of energy can damage our cells and our DNA faster than our body can repair the damage. These harmful waves are part of the electromagnetic spectrum that includes gamma rays, x-rays and some ultraviolet radiation. That's why health officials advise that people use sunscreen and why medical staff use protective blankets when patients receive X-ray exams.

Tory Bruno, CEO of the spaceflight company United Launch Alliance, spoke about radiation and the challenges it poses to a U.S. Mars-shot during a Feb. 28 presentation held at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Maryland. The chat was part of an all-day event called the Lunar Surface Innovation Consortium, where NASA officials, APL representatives and space industry leaders spoke about how NASA's Artemis program could unfold over the course of the decade.

Artemis' primary goal is to send a crewed mission back to the moon, with the first woman and the next man to land on the lunar surface on board. In its following chapter, Artemis would help engineers learn more about the deep space environment to safely send humans on long-duration missions to Mars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

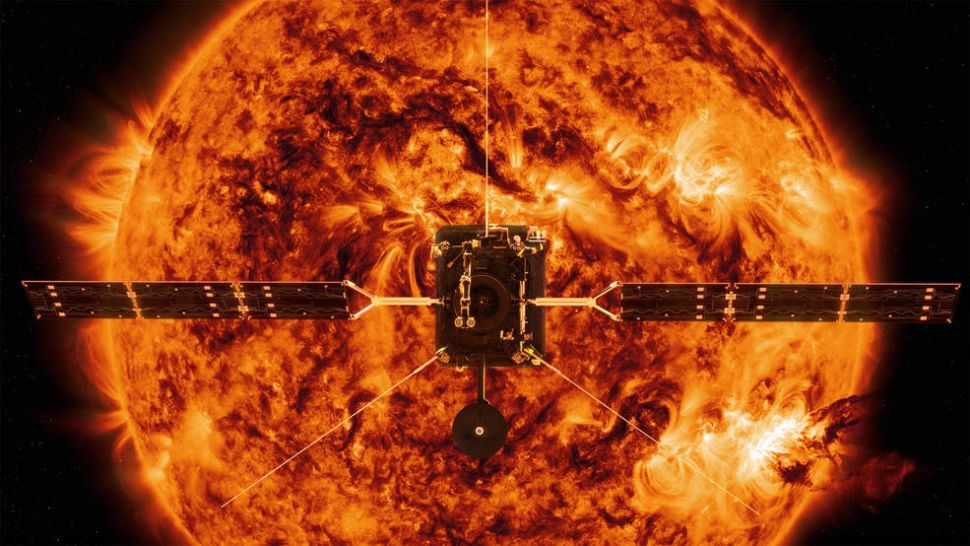

Bruno said that NASA is already getting a head start on these missions by studying the sun more intently. Missions like NASA's Parker Solar Probe, which launched in 2018, and a collaboration with the European Space Agency on the Solar Orbiter, which launched earlier this year, could inform the design and the timing of Mars missions based on the sun's cycles of activity by gauging when the sun is emitting levels of radiation higher than average.

In the presentation, Bruno outlined the traditional materials —— water, concrete, lead —— that are used as a containment barrier against radiation. But rockets aren't made of this stuff.

"We're going to need some new materials that are a lot more efficient at shielding out this radiation… but nothing that we could use today to safely send people to the Red Planet and back," Bruno said.

Although crew capsules have been sending people into space for over half a century, spacefarers haven't had to endure missions as long as what a mission to Mars would require.

Astronauts on the International Space Station don't have to worry a tremendous amount about radiation because most individual missions last six months to under a year. A roundtrip mission to Mars would require about 180 days, according to Bruno, and sending people to the Red Planet would only be worthwhile if they could spend weeks, months or even a full year there to explore Mars' environment.

It's hard to study this radiation environment from Earth —— sending experiments to the moon and to Mars and making rigorous observations will be essential to sending the first humans to Mars.

- Solar Orbiter: The US-European mission to explore the sun's poles in photos

- How to die on Mars

- Watch Clouds on Mars Drift by in Supercomputer Simulations

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.

-

Torbjorn Larsson ReplyAdmin said:Astronauts on the International Space Station don't have to worry a tremendous amount about radiation because most individual missions last six months to under a year.

More importantly, they share much of the same protection against solar wind (Earth magnetic field) and cosmic rays (half the spatial angle shielded by Earth) as non-astronauts do. It is just the protection from mainly cosmic rays hitting Earth that the atmosphere make that they lack.

Interplanetary travelers will lack that protection fully (between planets) or partially (near or on most planets). But I hear NASAs risk target is conservative, with at most a 5 % increased lifetime lethality. Half of the global population currently risk on average twice that by moving into cities mainly due to increased pollution (whether or not they are aware of the statistics; and the situation is improving). -

Catastrophe "There are already several robotic missions to the Red Planet, and sending humans there is an exciting future prospect."Reply

After this coronavirus episode is over, I do not believe the world will be the same place. So much is changing. TV interviews with guests speaking over a video link from their homes is now commonplace and I believe this is creating a mindset favouring robotic exploration.

I do accept that the time lag makes a major difference and I am not saying that I am a robot fan. Just that I believe there will be a new slant on exploration.

Of course mankind will continue on its fanatical path to contaminate the Universe so I am sure it will get there eventually (just my opinion) never fear! Perhaps a "hands off - do not touch" approach will do some good.

Cat ;)