Our Mars rover mission was suspended because of the Ukraine war — here's what we're hoping for next

On March 17, the European Space Agency (ESA)'s council and member states decided to suspend our mission.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Andrew Coates, Professor of Physics, Deputy Director (Solar System) at the Mullard Space Science Laboratory, UCL

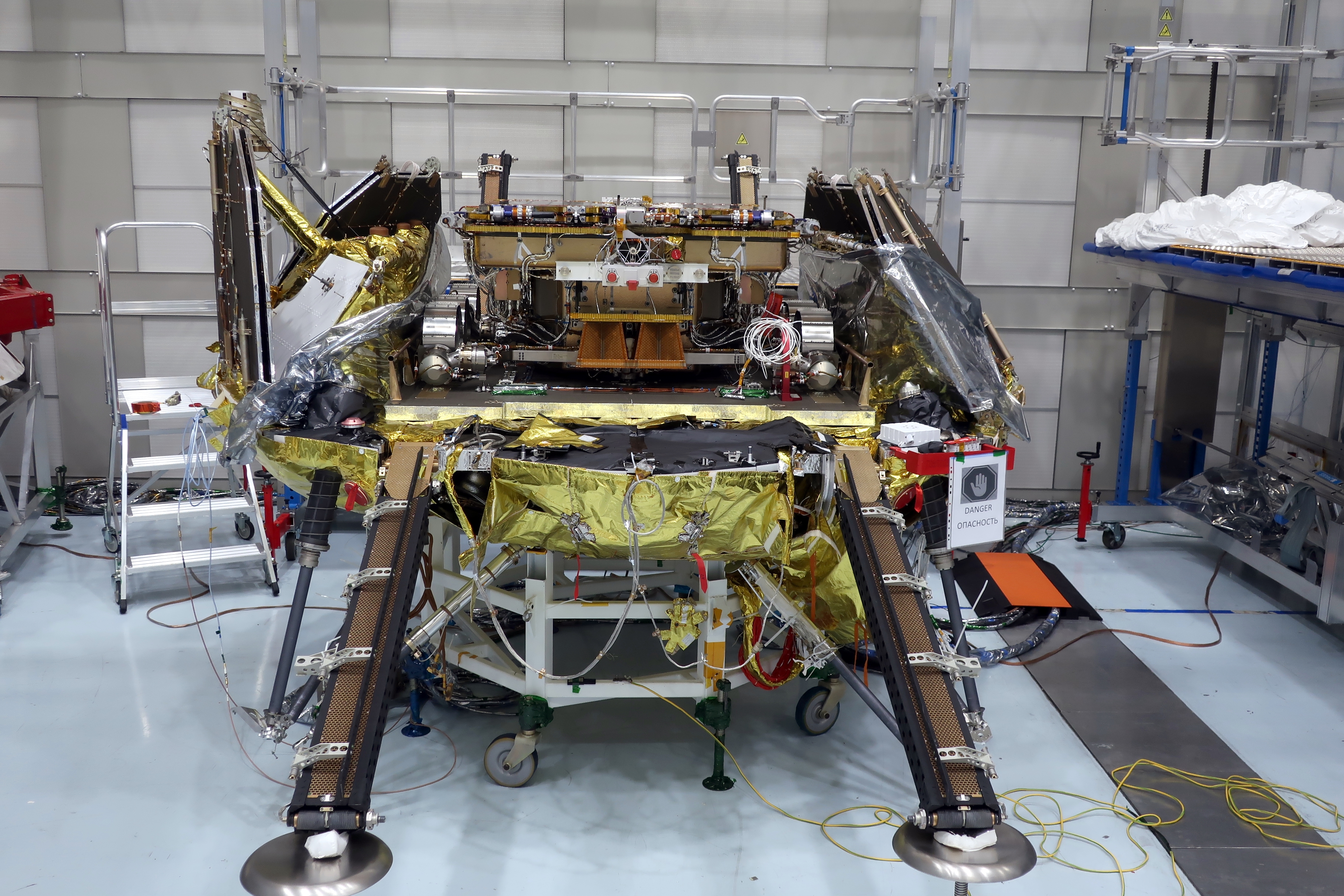

Just a few months ago, we were confidently expecting to launch our rover, Rosalind Franklin, to Mars in September as part of the ExoMars mission, a collaboration between Europe and Russia. The landing was planned for June 2023. Everything was ready: the rover, the operations team and the eager scientists.

The final preparations started in February 21, with part of our team heading to Turin, Italy, to carry out the final alignment and calibration tests. All was going well, though some of the team were slightly delayed by Storm Eunice in the U.K. Three days later, they had nevertheless finished the work — leaving some wonderful data, which would help us decide where Rosalind would drill on Mars. The industry team started packing the rover, which was ready to be shipped to the launch site.

Then, a storm far more powerful and tragic than Eunice descended on Ukraine: Russia's invasion. The situation developed in the next days and weeks, leading to a series of emergency meetings. On March 17, the European Space Agency (ESA)'s council and member states decided to suspend our mission. We won't know for sure what happens next until a study by ESA and industry partners reports back in July — but there are causes for optimism.

Related: The boldest Mars missions in history

The Rosalind Franklin rover is unique among all the rovers planned for Mars. It can drill deeper than any before it — up to 6.5 feet (2 meters) below the harsh surface. This is important as the subsurface is protected from harmful radiation, and could therefore contain signs of past or present life.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Rosalind's instruments include our PanCam, which is a camera that will do geology and atmospheric science on Mars — complemented by the other cameras and a sub-surface sounding radar. Rosalind will also collect pristine samples from below the surface which will be deposited in the "analytical drawer," where three instruments will do mineralogy and search for signs of life.

Some 3.8 billion years ago, at the same time as life was emerging on Earth, Mars was habitable too. There is evidence from orbiters and landers of water on the surface then — there would have been clouds, rain and a thick atmosphere. There was also a global protective magnetic field and volcanos. This means Mars essentially had all the right ingredients for life — carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulfur. If life emerged there like it did on Earth, we were on a track to find it.

The climate has changed significantly since Mars lost its magnetic field 3.8 billion years ago, though. The planet is now is dry, cold, has a thin atmosphere and a surface hostile for life. But below the surface, some living species may have survived, or remains of them could be conserved.

Other missions to Mars are looking for life too. The amazing NASA Perseverance rover landed in February 2021. Its scientists are partly guided by images from a NASA helicopter on the planet, called Ingenuity, and it recently reached an ancient river delta.

Perseverance is collecting samples from Jezero crater, ready to be brought back to powerful labs on Earth by the Mars sample return missions. The results will hopefully complement those from Rosalind Franklin — which will examine deeper samples from a different and slightly older site, Oxia Planum, where there is also abundant evidence of a watery past.

Options for Rosalind

Russia was meant to help launch Rosalind Franklin on one of its rockets. While a European-built spacecraft would then take it to Mars, a Russian-built platform would again be needed to land it. Russia was also meant to provide radioactive heaters to keep the batteries of the rover warm in the cold Martian nights.

Now, ESA is looking at options. Given that continuing with Russia in 2024 is most unlikely, the main possibilities are either ESA going it alone, or teaming up with a partner such as NASA. ESA's new Ariane-6 rocket, which is nearly ready, could help launch the rover, as could a SpaceX rocket. For the lander and heaters, ESA would need to develop these alone or in collaboration with NASA, by adapting existing technology.

It could therefore take time. What's more, because of the way the planets orbit the sun, there are opportunities for launches to Mars only every two years: in 2024, 2026 and so on. My expectation is that 2028 is most likely for our mission, but it will require hard work. The positive thing is that ESA and the member states are still keen to go ahead, and we are eagerly looking forward to the launch whenever that will be.

Ultimately, life changed for the Rosalind Franklin team on February 24. I've been working on the mission since 2003, when we first proposed a camera system for what became ExoMars. We had already provided the "stereo camera system" for ESA's ill-fated Beagle 2, which very nearly worked when it landed on Christmas Day 2003. But orbiter images later showed that the last solar panel didn't quite unfurl, so communications with Earth were impossible. The wait for data from the Martian surface for our team goes on.

There is no getting away from the huge disappointment we felt when the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin rover that we had worked on for almost 20 years was suspended. But it was ultimately a necessary and understandable step, and we now look forward to a future launch.

This still is cutting-edge science, and it will be for the rest of this decade. Due to the uniquely deep drilling, Rosalind Franklin still may be the first mission to find signs of life in space.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

I am Professor of Physics and Deputy Director (Solar System) at the Mullard Space Science Laboratory (MSSL), University College London, located in Surrey.

My specialty is the plasma interaction with unmagnetized objects, such as comets, Titan, Enceladus, Venus, and Mars, planetary magnetospheres, and planetary exploration. Through my career I've been lucky to work on many of the planetary and magnetospheric missions with plasma instruments on board. One of these was Cassini, which I've been fortunate to have been involved with (as lead co-investigator for the Electron Spectrometer (ELS), part of the Cassini Plasma Spectrometer (CAPS) since the instrument proposal in 1989. This included selection, getting the money, design, build, test, test, and test, calibrate launch, arrival at Saturn, the prime mission to 2008, equinox mission to 2010—and it still worked well (until 2012) into the recent (extended-extended) "Solstice" mission (North polar summer on Saturn) with the spectacular end of mission in 2017.