No, NASA's Opportunity rover has not yet awakened from its long slumber on Mars.

Excitement rippled through Twitter yesterday afternoon (Nov. 15) as word spread that NASA's Deep Space Network (DSN), the system of big radio dishes the agency uses to communicate with its farflung spacecraft, may have picked up a ping from Opportunity.

That would have been a very big deal, because Oppy hasn't made a peep since June 10. Around that time, a huge dust storm boiled up around the solar-powered rover, blocking so much sunlight that Oppy couldn't recharge its batteries and was forced into a sort of hibernation. [Mars Dust Storm 2018: What It Means for Opportunity Rover]

But alas, space fans' hopes were quickly dashed.

"Today http://eyes.nasa.gov/dsn/dsn.html showed what looked like a signal from @MarsRovers Opportunity. As much as we'd like to say this was an #OppyPhoneHome moment, further investigation shows these signals were not an Opportunity transmission," officials at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, which manages Opportunity's mission, said via Twitter yesterday.

"Test data or false positives can make it look like a given spacecraft is active on http://eyes.nasa.gov/dsn/dsn.html. We miss @MarsRovers Opportunity, and would be overjoyed to share a verified signal with you. Our work to re-establish comms continues," JPL officials added in another tweet.

That work consists of both beaming commands to Opportunity and listening for any signals the venerable rover may be sending home. NASA officials have said they will continue this "active listening" campaign at least through January.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

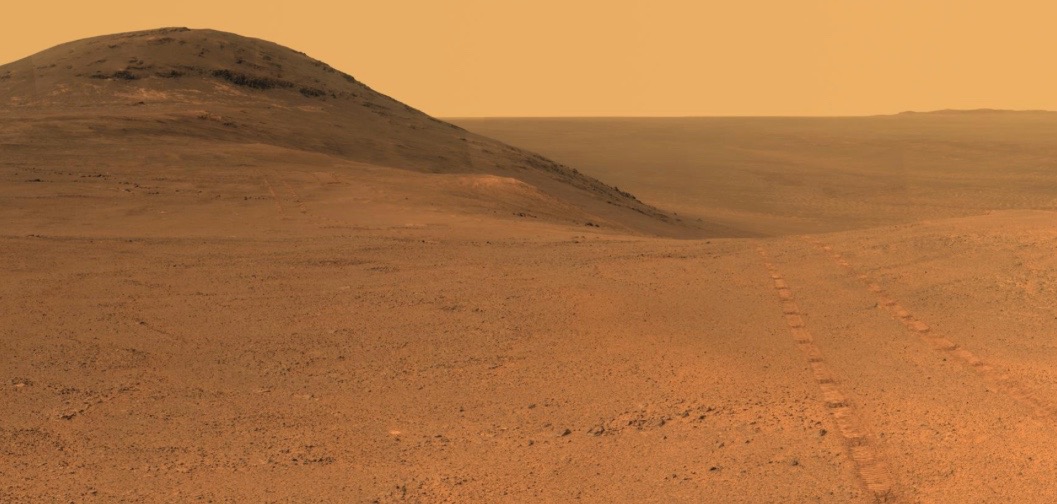

The hope is that dust-covered solar panels are the only thing keeping Opportunity down, and that strong winds will soon come through and blast the panels clean, finally allowing the robot to power up once again. Indeed, it is now the windy season in Oppy's location — the rim of the 14-mile-wide (22 kilometers) Endeavour Crater, just south of the Martian equator, NASA officials have said.

The Mars dust storm that silenced Opportunity went global by June 20. But a month or so later, it had started dying down. And by mid-September, skies over Endeavour Crater were clear enough that Oppy's handlers decided to kick off the active listening campaign.

Opportunity landed on Mars in January 2004, a few weeks after its twin, Spirit, touched down in a different part of the Red Planet. The golf-cart-size rovers were tasked with hunting for signs that liquid water flowed across Mars in the ancient past — and both found plenty of such evidence.

Spirit and Opportunity were originally supposed to roam for just 3 months, but the rovers proved incredibly hardy. Spirit kept rolling along until 2010, and Oppy was doing just fine until the dust storm flared up.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate) is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.