Perseverance rover confirms existence of ancient Mars lake and river delta

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

NASA chose the landing site of its life-hunting Perseverance Mars rover wisely.

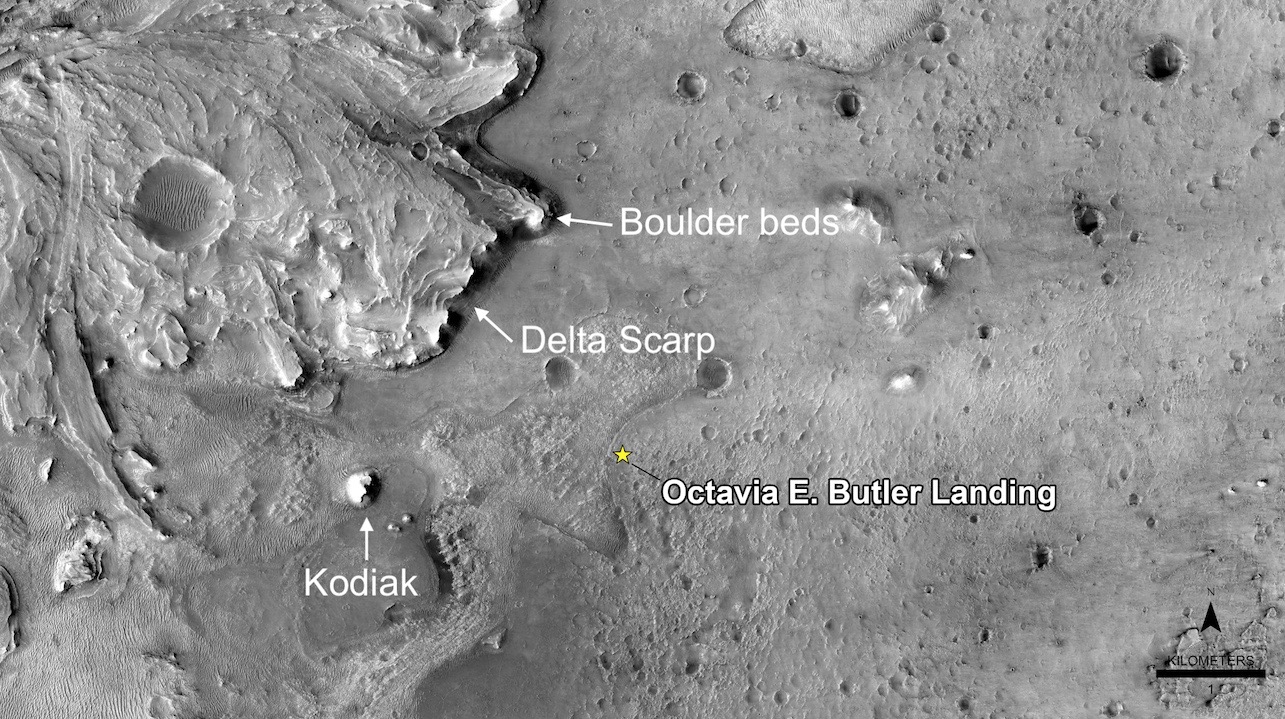

Perseverance touched down in February on the floor of the 28-mile-wide (45 kilometers) Jezero Crater, which was picked primarily because previous observations by Mars orbiters suggested that it hosted a big lake and a river delta in the ancient past.

Photos snapped by Perseverance early in its mission, before the car-sized robot even started roving, confirm this interpretation, a new study reports.

"Without driving anywhere, the rover was able to solve one of the big unknowns, which was that this crater was once a lake," study co-author Benjamin Weiss, a professor of planetary sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said in a statement. "Until we actually landed there and confirmed it was a lake, it was always a question."

Related: Where to find the latest Mars photos from NASA's Perseverance rover

A good site for a bold mission

Perseverance has two main tasks during its $2.7 billion mission: hunt for signs of past Mars life and collect and cache dozens of samples for future return to Earth. (The rover also supported and documented the first few sorties of its traveling companion, NASA's Ingenuity Mars helicopter, which is now flying more independently on the Red Planet.)

Jezero Crater was deemed a good place to do this work, based on data gathered by spacecraft such as NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Orbital imagery showed a fan-shaped feature in Jezero that mission team members interpreted as a delta — a place where a river emptied into a lake about 3.7 billion years ago, depositing sediments that could harbor evidence of ancient Martian microbes, if any ever existed.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

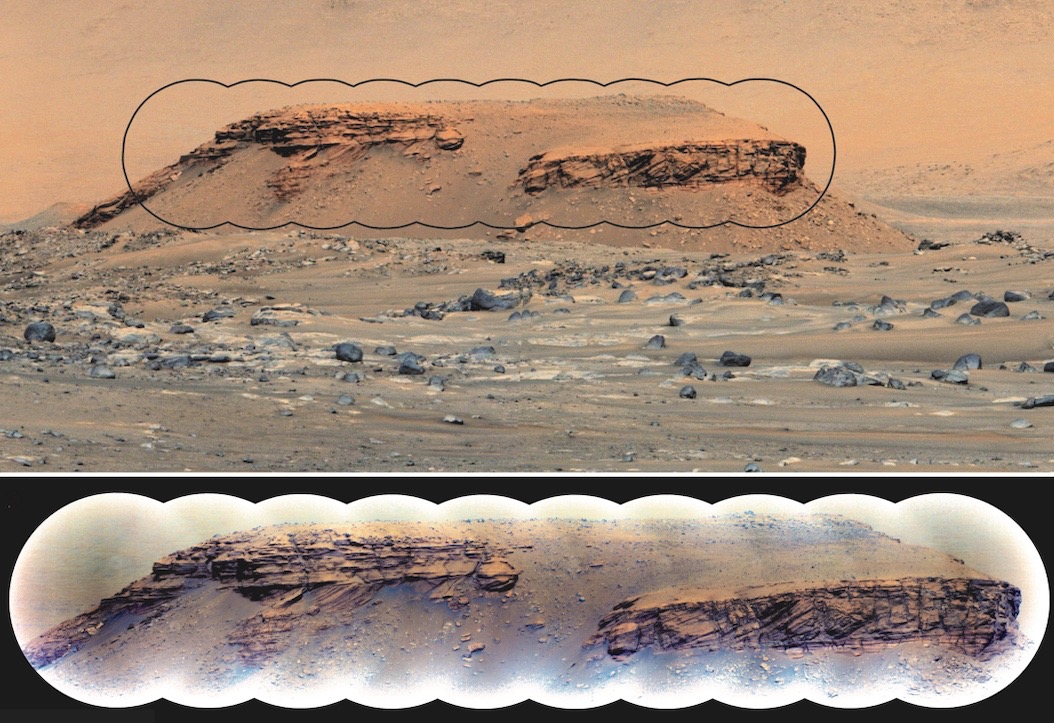

In the new study, which was published online today (Oct. 7) in the journal Science, researchers analyzed early photos that Perseverance snapped of this putative delta from afar with its Mastcam-Z imaging suite and a camera on its rock-zapping SuperCam instrument.

These photos captured the edge of the large delta outcrop as well as an isolated butte dubbed "Kodiak," which the team thinks is an erosional remnant of the same formation. The Kodiak imagery was especially sharp, and the team saw in it distinct layers of sediment that could only have been deposited by a river flowing into a lake.

The Kodiak observations "point unambiguously toward a deposition of river [sediments] with a delta and a lake," study co-lead author Nicolas Mangold, of the French National Center for Scientific Research and the University of Nantes, told Space.com via email. (The other co-lead author is Sanjeev Gupta, of Imperial College London.)

"This helps us to constrain the lake level and will help us to build a scenario of the delta formation and lake activity along Perseverance's traverse, and also identify the right layers to analyze and sample," Mangold said.

Interestingly, Perseverance's observations show that the ancient Jezero lake was about 330 feet (100 meters) lower than orbital data had suggested, "marking a phase of the delta well after the start of its formation," Mangold said.

"We cannot extrapolate to the start of Jezero evolution, before the deposition of the material at Kodiak, because the corresponding layers are hidden further away in the delta," he added. "But Perseverance might be able to give more results on that when it will cross the delta."

Water on Mars: Exploration and evidence

A changing Jezero

Jezero is bone-dry today, like the rest of the Martian surface. Scientists think the Red Planet dried out about 3.5 billion years ago, after its global magnetic field died and its once-thick atmosphere became susceptible to stripping by charged particles streaming from the sun.

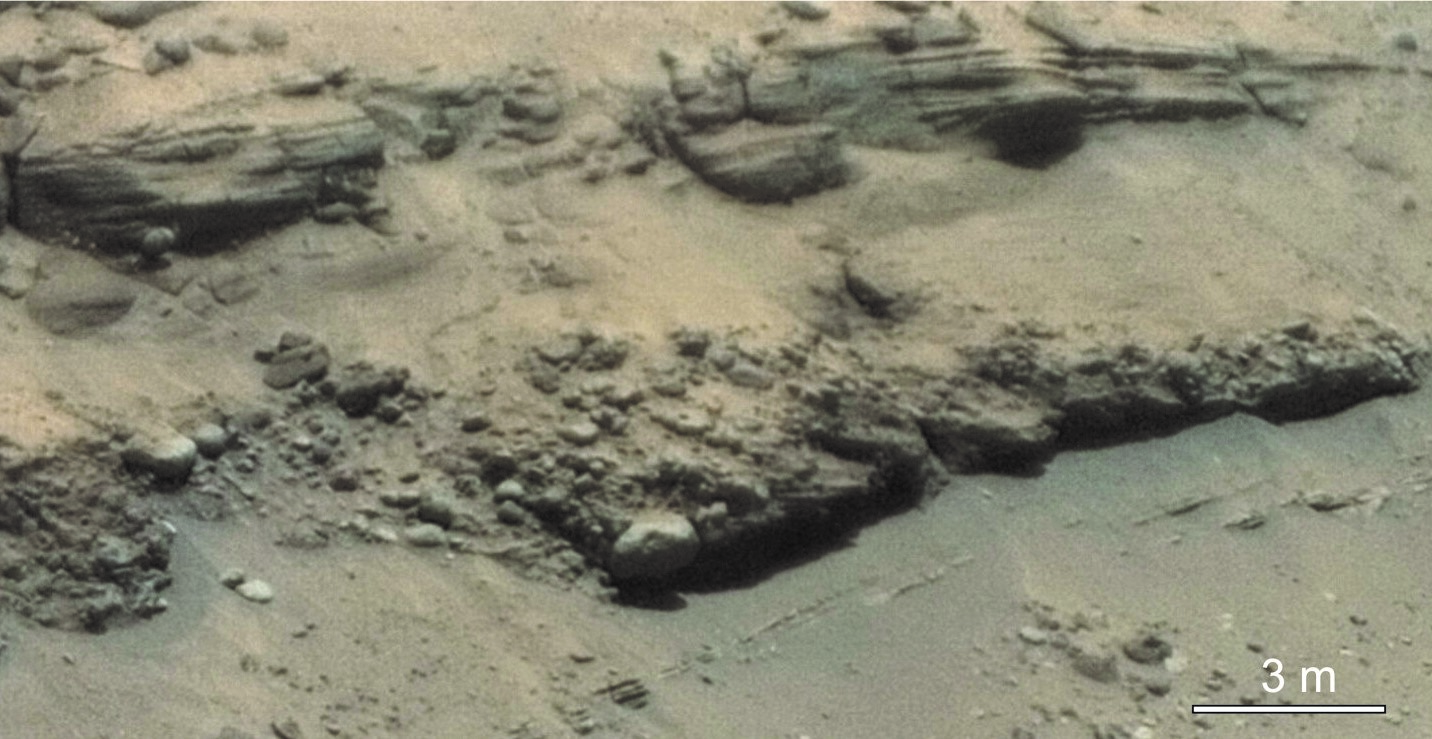

The newly analyzed photos may provide an intriguing glimpse into this big shift. For example, Perseverance's imagery also shows big boulders, some up to 5 feet (1.5 m) wide, in the upper (younger) layers of Jezero's main delta outcrop. It took a powerful flow to transport such large rocks — likely a flood that moved up to 106,000 cubic feet (3,000 cubic m) of water per second, study team members said.

Such flows may have resulted from "glacial surges" or rainfall-induced flash floods like those that occur in some of Earth's desert regions today, Mangold said. Regardless of the cause, the boulder-bearing deposits could point to a very different Jezero than the one that produced the earlier lake sediments.

"The most surprising thing that’s come out of these images is the potential opportunity to catch the time when this crater transitioned from an Earth-like habitable environment to this desolate landscape wasteland we see now," Weiss said in the same statement. "These boulder beds may be records of this transition, and we haven’t seen this in other places on Mars."

Perseverance will eventually get some up-close looks at the delta formation, if all goes according to plan. The team aims to drive the rover, which has traveled 1.62 miles (2.61 km) on Jezero's floor to date, over to the delta outcrop and collect samples deposited during the calm-lake era. (Perseverance has already collected two of a planned several dozen samples, which will be hauled to Earth by a joint NASA-European Space Agency campaign, perhaps as early as 2031.)

But Perseverance, and NASA's other Mars robots, are temporarily standing down because the Red Planet is on the other side of the sun from Earth at the moment. Our star can corrupt Mars-bound commands in the current planetary configuration, so NASA has imposed a two-week communications blackout that ends on Oct. 16.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.