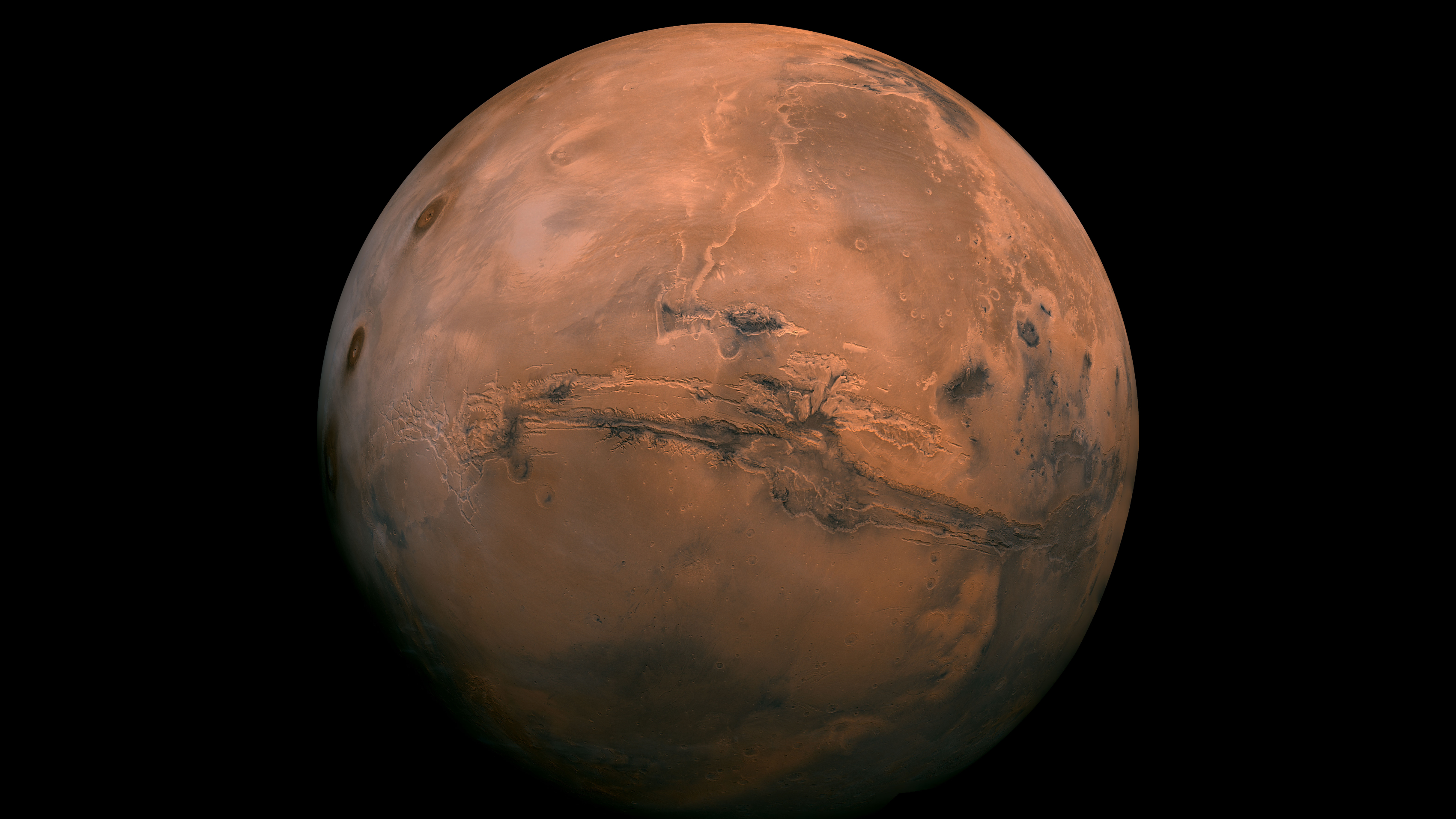

Mars' suspected underground lake could be just volcanic rock, new study finds

The "lake" might be a "dusty mirage."

A suspected Martian underground lake is probably volcanic rock masquerading as water, according to a new study.

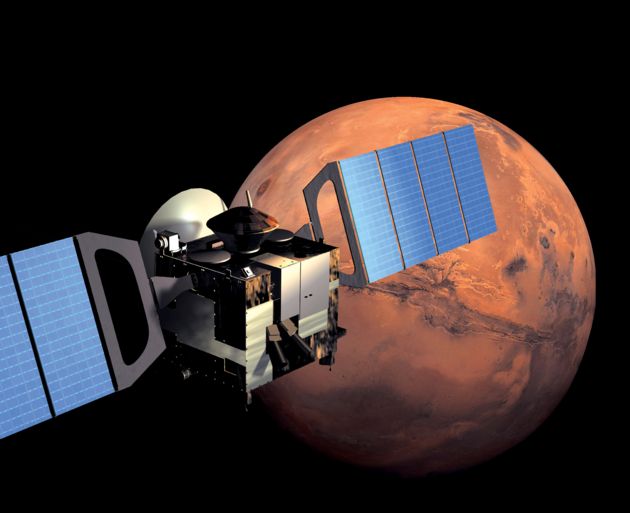

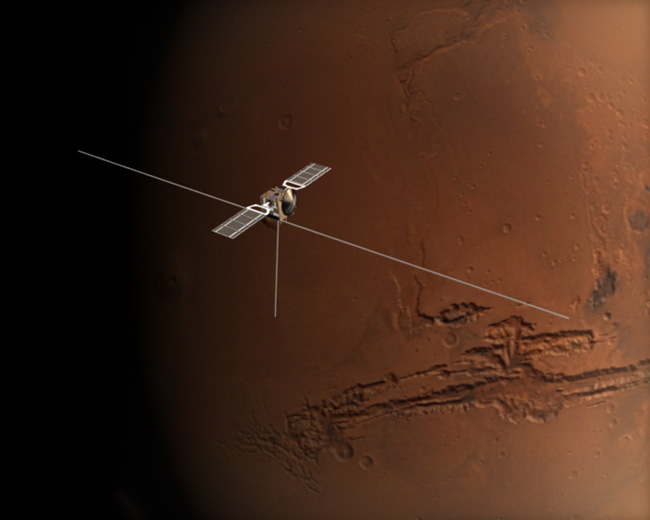

In 2018, researchers found evidence that the Red Planet's southern pole might have water beneath it. The possible water signature was first interpreted from radar observations made by Mars Express, a European Space Agency spacecraft. But a new study contradicts these findings and suggests that the spacecraft was likely just looking at volcanic rock.

"For water to be sustained this close to the surface, you need both a very salty environment and a strong, locally generated heat source, but that doesn’t match what we know of this region," Grima said in a press statement, which described the water findings as a "dusty mirage."

Related: Largest canyon in the solar system revealed in stunning new images

Additionally, the presence of water doesn't fit with what researchers have understood about Mars' southern pole, study lead author Cyril Grima, a planetary scientist at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, said in the statement.

Mars, a dusty and windy planet, does have ice water locked up at the poles. But scientists are still working to determine how much water might actually be lurking below the planet's surface. The amount of Martian water that both once existed and could currently exist could inform our understanding of life and the possibility of life on Mars, and it could also support future astronauts who might one day step foot on the planet's surface.

In 2018, scientists were building on three decades of theories suggesting there might be water beneath the polar caps of Mars, just like we see on Earth beneath the ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Initially, scientists thought they had spotted water signals using radar data gathered by a Mars Express instrument called MARSIS, which uses radar pulses to study the planet's interior and ionosphere (a part of the atmosphere). But further study was needed to confirm suspected findings and their implications.

Grima and his team worked to attempt to place the radar signatures in a global context. To do this, they placed an imaginary global ice sheet across a planet-wide radar map, generated with three years of MARSIS data. This technique allowed the team to compare how the Martian terrain would appear through a simulated mile-deep (1.6 km-deep) glacier, which allowed the scientists to compare features.

Under these conditions, the bright reflections spotted at the pole matched other reflections found in volcanic plains, the team realized. Because of this, they suspect that the radar's polar observations were picking up either iron-rich lava flows or mineral deposits in dried riverbeds, not water.

While their result defies the existence of substantial water reserves in that region, this work still helps us to better understand how Mars formed, the team said in their study, which was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters on Monday (Jan. 24).

The terrains studied in this work are not "expected to host water-bearing materials," the study stated. But better characterizing these regions, the authors added, could lead to a better understanding of their composition, which in turn would help generate models of how these rocks were formed.

While the findings with Mars Express in 2018 were a major step in understanding Mars and its possible water reserves, the first to suggest that water could be hiding below Mars' polar ice caps was Steve Clifford, now a planetary scientist specializing in water on Mars at the Planetary Science Institute based in Arizona. (Clifford was not involved in either of the studies.)

Clifford was cautious in 2018 about drawing immediate conclusions that Mars Express found water. "I think it's a very, very persuasive argument, but it's not a conclusive or definitive argument," Clifford told Space.com at the time. "There's always the possibility that conditions that we haven't foreseen exist at the base of the cap and are responsible for this bright reflection."

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.