Mars is leaking water into space during dust storms and warmer seasons

Water is leaking from Mars' atmosphere through changing seasons and swirling Martian storms, scientists found in two new studies.

There is water on Mars, but it seems to only exist either in ice caps at the planet's poles or as gas in the planet's thin atmosphere. Water has been escaping the planet for billions of years, since Mars lost its magnetic field (and subsequently much of its air and water), and two new studies show how water moves through and leaves the planet's atmosphere.

The two new studies, led by Anna Fedorova, a researcher at the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences and Jean-Yves Chaufray, a scientist at the Laboratoire Atmospheres Observations Spatiales in France, use data from the European Space Agency's (ESA) ExoMars orbiter, which began its main science mission in 2018, and ESA's Mars Express orbiter, which to show that the escape rate of mars' water is determined by changing weather and climate on Mars and the planet's distance from the sun.

"The atmosphere is the link between surface and space, and so has much to tell us about how Mars has lost its water," Fedorova said in an ESA statement.

Related: Mars may be wetter than we thought (but still not that habitable)

In these studies, the teams used data from ExoMars' SPICAM (Spectroscopy for the Investigation of the Characteristics of the Atmosphere of Mars) instrument, which observed Mars' atmosphere.

"We studied the water vapor in the atmosphere from the ground up to [62 miles] 100 kilometers in altitude, a region that had yet to be explored, over eight Martian years," Fedorova said. (One year on Mars is about two Earth year.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

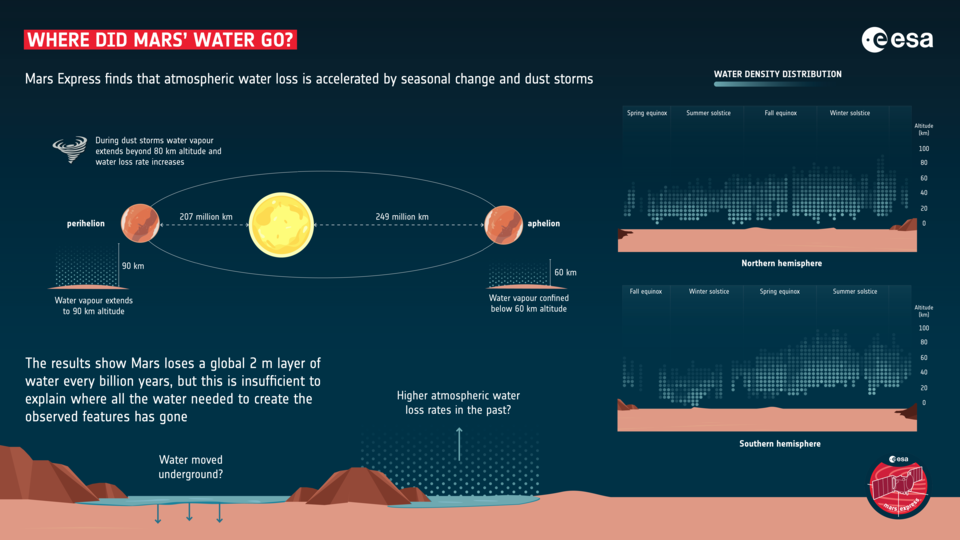

The researchers found that when the planet is farthest from the sun, at about 250 million miles (400 million km) away, water vapor in Mars' atmosphere really only exists less than 37 miles (60 km) from the planet's surface. However, when the planet is closest to the sun, at about 207 million miles (333 million kilometers), water can be found as far out as 56 miles (90 km) above the surface.

When Mars and the sun are farther apart, the cold makes the water vapor at a certain altitude in Mars' atmosphere freeze out, but as the planet gets closer and warmer, that water can circulate farther. Because water vapor can travel out farther in Mars' atmosphere during warmer seasons, those are also the times when the planet loses more water.

"The upper atmosphere becomes moistened and saturated with water, explaining why water escape rates speed up during this season — water is carried higher, aiding its escape to space," Fedorova added.

But it's not just seasons that dictate how much of Mars' water leaks out into space; dust storms also play an important role, the researchers found in these studies. In poring over eight years of data, the scientists found that in the years that Mars experienced global dust storms, water traveled higher in the planet's atmosphere. In these years, the researchers found water vapor over 50 miles (80 km) from the planet's surface.

The scientists found that every billion years, Mars loses the equivalent of "a global [six feet] two-meter-deep layer of water," according to the statement.

"This confirms that dust storms, which are known to warm and disrupt Mars' atmosphere, also deliver water to high altitudes," Fedorova said. "Thanks to Mars Express' continuous monitoring, we were able to analyze the last two global dust storms, in 2007 and 2018, and compare what we found to storm-free years to identify how the storms affected water escape from Mars."

Still, this work does not fully explain the amount of water that Mars has lost over the past 4 billion years, according to the statement. "A significant amount must have once existed on the planet to explain the water-created features we see," Chaufray said. "As it hasn't all been lost to space, our results suggest that either this water has moved underground, or that water escape rates were far higher in the past."

These two studies were published Dec. 11, 2020, in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets and Jan. 1 in the journal Icarus.

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Chelsea “Foxanne” Gohd joined Space.com in 2018 and is now a Senior Writer, writing about everything from climate change to planetary science and human spaceflight in both articles and on-camera in videos. With a degree in Public Health and biological sciences, Chelsea has written and worked for institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine and Live Science. When not writing, editing or filming something space-y, Chelsea "Foxanne" Gohd is writing music and performing as Foxanne, even launching a song to space in 2021 with Inspiration4. You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd and @foxannemusic.