Water on Mars may have flowed for a billion years longer than thought

New evidence finds substantial water on the surface as late as 2 billion years ago.

Observations by a long-running Mars mission suggest that liquid water may have flowed on the Red Planet as little as 2 billion years ago, much later than scientists once thought.

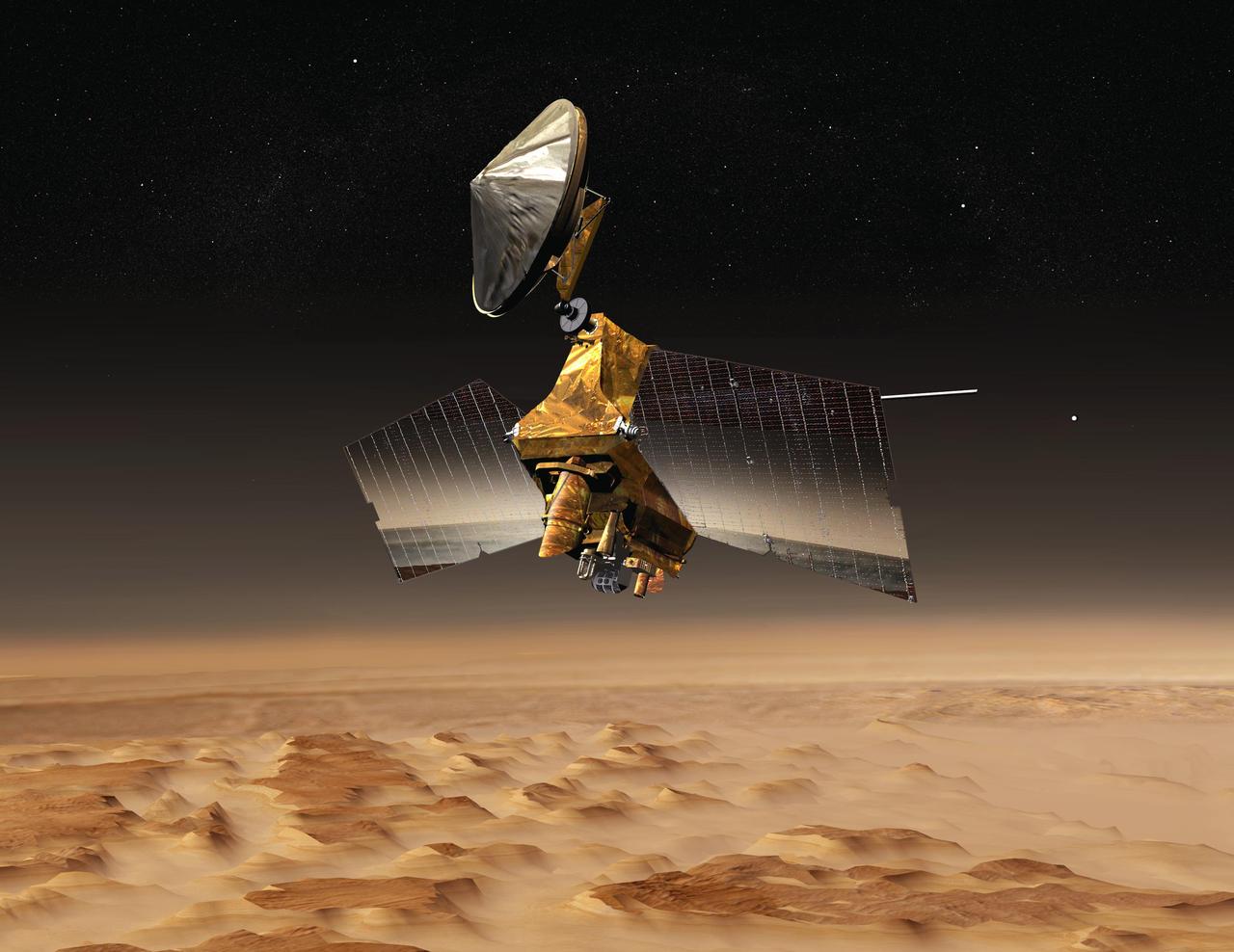

Scientists charted the presence of chloride salt deposits left behind by flowing water using years of data from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), which has been orbiting the Red Planet since 2006.

By studying dozens of images of salt deposits taken by the spacecraft's Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), the scientists interpreted a younger age for the salt deposits using a method "crater counting." The younger a region is, the fewer craters it should have, with adjustments for aspects such as a planet's atmosphere, allowing scientists to estimate its age.

The new results push forward the existence of water on Mars from 3 billion years ago to as little as 2 billion years ago, based on the observations, which could have implications for life on Mars and more broadly, the planet's geological history.

"Part of the value of MRO is that our view of the planet keeps getting more detailed over time," Leslie Tamppari, MRO's deputy project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a statement. "The more of the planet we map with our instruments, the better we can understand its history."

Related: Scientists spot water ice under the 'Grand Canyon' of Mars

The scientists also created elevation maps using MRO's wide-angle context camera, and the zoomed-in views provided by the High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) that can spot craters as small as the Curiosity or Perseverance Mars rovers.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The salt minerals were first spotted by a different spacecraft 14 years ago, called Mars Odyssey, but MRO's advantage is it has higher resolution instruments than its older (and still operational) companion in orbit.

A study based on the research was published Dec. 27, 2021 in AGU American Geophysical Union Advances. The study was led by Ellen Leask, who did much of the work during doctoral stories at the California Institute of Technology. Her supervisor and co-author is Bethany Ehlmann, a planetary scientist at the same institution.

Scientists have performed numerous studies in recent years to assess the extent of flowing water on Mars, both up close through surface missions and using orbital data. Just days ago, a suspected underground reservoir of water at the Martian southern pole was debunked using new interpretations of the data.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.