Mars is a 'winter wonderland' in this frosty (and stunning) image from space

The new image from Europe's Mars Express probe is a festive treat.

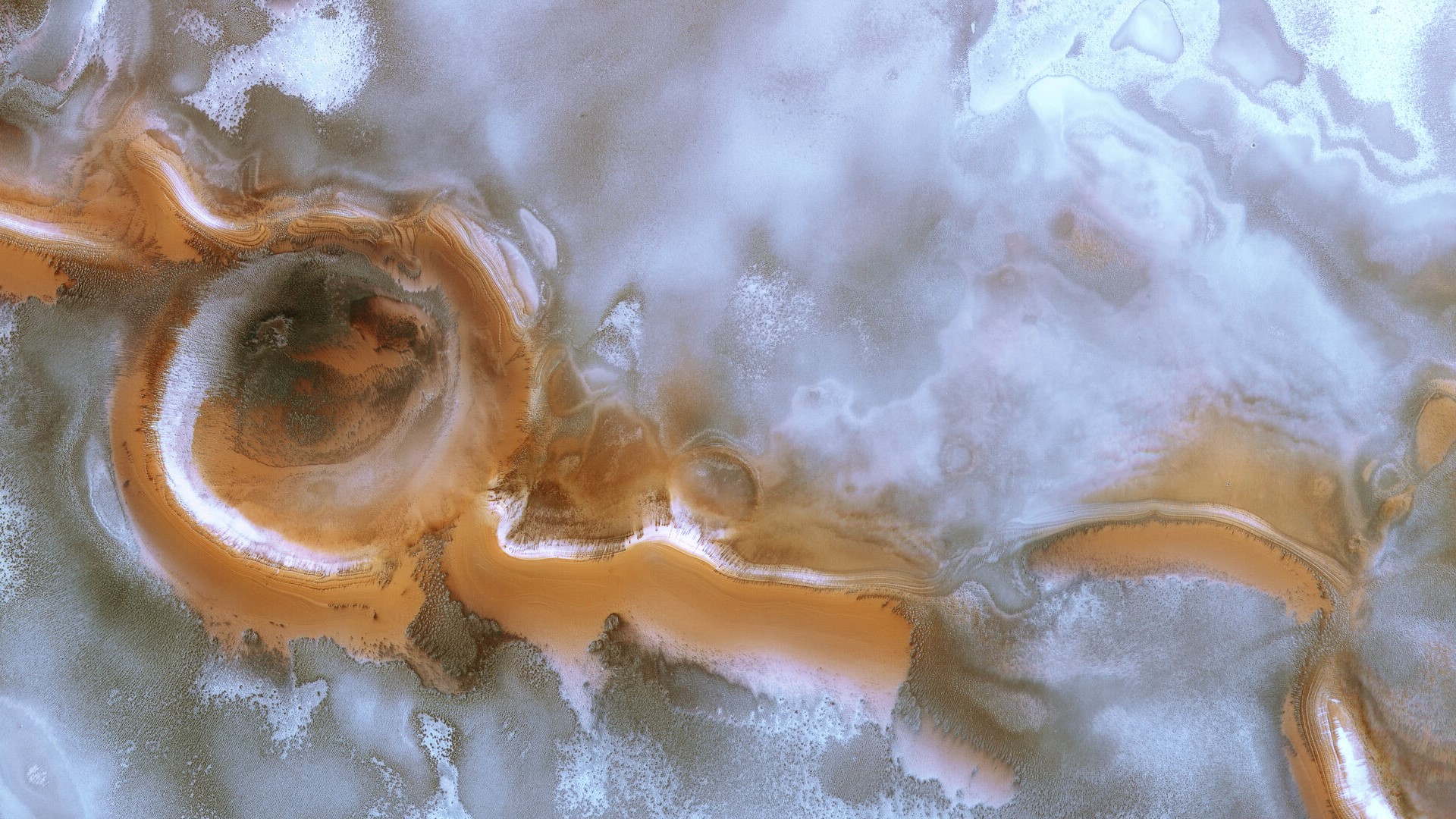

A newly released image of Mars shows an icy scene, with ribbons of red and white dancing across a frosty landscape near the planet's south pole.

While the snowy scene may evoke the feeling of a "winter wonderland" on the Red Planet, it was actually captured by the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter on May 19. This means that the frigid image actually represents spring in the Martian southern hemisphere and the Martian ice was beginning to recede.

Just six days before much of Earth marks a new year, on Dec. 26, the Red Planet will commence its own new year, which will last 687 Earth days. The planet has four seasons, winter, spring, summer and autumn, and just like on Earth, the Red Planet's winter is cold and summer warm, although winter is much colder than ours, with temperatures on Mars dropping as low as minus 76 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 60 degrees Celsius).

Related: This icy crater near Mars' north pole is a winter wonderland (photos)

The yuletide period is special for Mars Express too: Christmas Day 2022 marks 19 years since the spacecraft arrived at Mars.

Arguably the most prominent features in the newly released image are two massive impact craters, banded with alternating layers of water ice and sediments called "polar layered deposits." These deposits can also be seen in the ridge that stretches between the two craters.

As the ice is depleted, more elevated regions appear frost-free, and throughout the image dark dunes poke through the surface frost in other areas. Dune fields appear as sharp ridges that run parallel to the most prevalent wind direction and in line with the shape of the underlying features.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists think that the dust that fills these dunes is dark because it originates from buried material from volcanoes that erupted in Mars' ancient history that was eventually exposed to strong Martian winds that easily carried it across the Red Planet's surface.

Other dark spots in the image represent this dust and the action of jets that erupt through the icy surface when underlying carbon dioxide ice is transformed straight into gas, a process called sublimation. These jets cause geysers of dust to launch into the Martian atmosphere, then settle in dark splotches on the surface of the planet.

These aren't the only elements in the image caused by sublimation, however. The polar region is punctuated by a number of large, irregularly shaped features produced by sublimating ice. These look like empty lakes gouged into the surface of Mars, with a pronounced example of this visible in the upper left-hand corner of the new image.

Monitoring these features from orbit means that scientists can observe the processes that are shaping the Martian surface and changing the appearance of the polar regions.

But the picture of spring in the southern hemisphere of Mars isn't just replete with surface features. Also visible are hazy clouds over the Martian surface. Particularly visible across the center of the image, these clouds contain water ice and their trajectory is, in part, influenced by the topography of the surface terrain beneath them.

During the Martian winter, carbon dioxide is deposited at both Martian poles as ice, which then thaws and sublimates in springtime. The release of gas back into the Martian atmosphere increases atmospheric pressure and causes strong winds.

In turn, these winds drive the tremendous exchange of material between the surface and atmosphere of Mars throughout the Martian year.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.