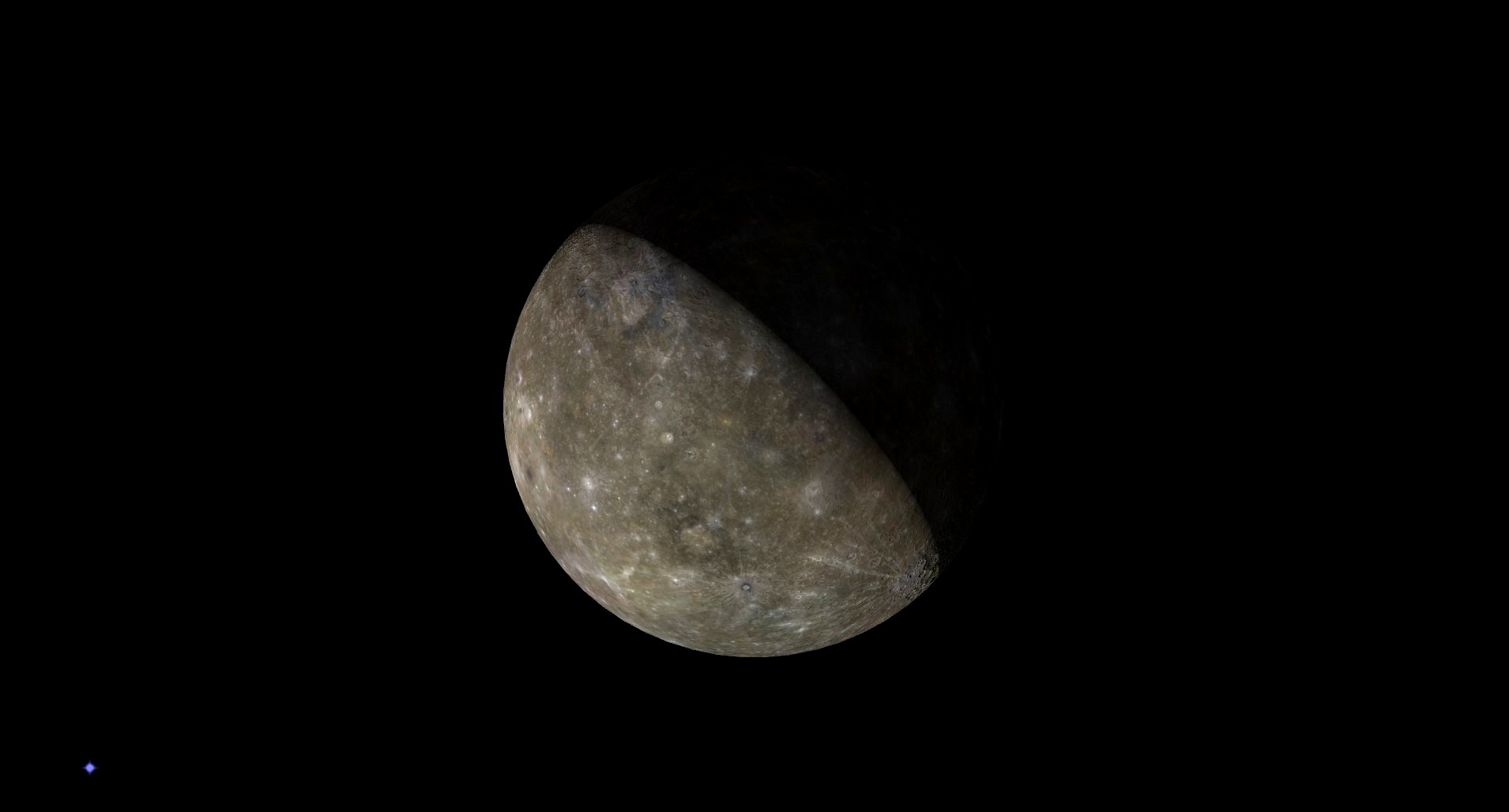

See the elusive planet Mercury at its best and brightest on Friday

The elusive planet Mercury reaches its furthest point from the sun on Friday (Jan. 12), with this separation allowing skywatchers a chance to spot the tiny planet.

The fact that Mercury is the closest planet to the sun means that it is often washed out by the light from our star and thus not visible. When the planet reaches its largest separation from the sun during its orbit, known as greatest elongation, it becomes more easily visible from Earth.

This greatest elongation will occur on Friday morning (Jan. 12) at around 10 a.m. EST (1500 GMT) when Mercury will be around 24 degrees away from the sun, according to EarthSky.

At this time, Mercury, also the smallest planet in the solar system, will have a magnitude of around -0.5, with the minus prefix indicating a particularly bright object over Earth. Mercury will appear in the constellation of Sagittarius at the time of greatest elongation, according to In the Sky.

Looking for a telescope to see the planets of the solar system up close? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

Mercury's points of greatest elongation happen during the tiny planet's 88-Earth-day orbit around the sun as it passes between our planet and our star. This happens roughly every 116 days, a cycle which astronomers call Mercury's synodic period.

Following greatest elongation, Mercury speeds ahead of Earth, fitting for a world that shares its moniker with the equally fleet-footed messenger of the gods in Roman mythology.

Periods when Mercury is visible over Earth are referred to as "apparitions," and they generally last a few weeks, occurring in the evening or in the mornings, with these apparition times alternating between one another.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The time of day at which the apparition of Mercury occurs depends on which side of the sun the planet is on as it approaches, reaches and then recedes from its point of greatest elongation. So, for instance, when Mercury is to the east of the sun, it rises and sets a short time after the sun and it is visible in the later afternoon/evening, its evening apparition. Conversely, when the planet is to the west of the sun, Mercury rises and sets before the star, and this is its morning apparition phase.

Mercury climbs to between 9 and 21 degrees above the horizon at sunset during evening apparitions, and during morning apparitions, Mercury reaches between 11 and 19 degrees over the horizon at sunrise. These times depend on the time of year at which the apparitions occur. (10 degrees in the sky corresponds roughly to the width of your fist at arm's length.)

The current phase of Mercury's morning apparitions kicked off at the end of December 2023. Following the greatest elongation on Jan. 12, Mercury remains bright but will once again begin moving ahead of Earth, bringing the planet ever closer to the sunrise. The tiny planet will continue to brighten until February, at which time it slips back into the glare of the sun.

If you are hoping to catch a look at Mercury or anything else in the night sky, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

If you're looking to snap photos of the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to photograph the planets, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor's Note: If you snap an image of Mercury and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.