What messages have we sent to aliens?

These messages might just be shots in the dark.

In the early 19th century, Austrian astronomer Joseph Johann Von Littrow earnestly proposed that humans dig trenches configured in vast geometric patterns in the Sahara desert, fill them with kerosene and light them ablaze. The idea was to send a clear message to alien civilizations living elsewhere in the solar system: We are here.

Von Littrow never saw his idea come to fruition. Still, long after he proposed his ambitious plan, we haven't stopped our attempts to contact extraterrestrial life.

So, what messages have we sent to aliens?

Related: Are aliens ignoring us?

Radio actualized the quest to declare Earth's existence. In 1962, Soviet scientists aimed a radio transmitter at Venus and saluted the planet in Morse code. This introduction, the first of its kind, included three words: Mir (Russian for "peace" or "world"), Lenin and SSSR (the Latin alphabet acronym for the Cyrillic name of the Soviet Union). The message was considered largely symbolic, according to a 2018 article published in the International Journal of Astrobiology. More than anything, it was a test run for a brand-new planetary radar, a technology which sends radio waves into space, with the primary goal of observing and mapping objects in the solar system.

In terms of distance, the next attempt to reach ET was far more ambitious. In 1974, a team of scientists, including astronomers Frank Drake and Carl Sagan, transmitted a radio message from the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico toward Messier 13, a cluster of stars about 25,000 light-years away. The image, sent in binary code, depicted a human stick figure, a double-helix DNA structure, a model of a carbon atom and a diagram of a telescope.

"The Arecibo message tried to give a snapshot of who we are as human beings in the language of math and science," Douglas Vakoch, a psychologist and the president of Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence (METI) International told Live Science.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Arecibo message was, quite literally, a shot in the dark. It will take around 25,000 light-years to reach Messier 13 — at which point, the star cluster will have moved, according to the Cornell University Department of Astronomy. Hypothetical aliens might still be able to detect the signal as it whizzes past — it has 10 million times the intensity of radio signals from our sun. (The sun emits a wide spectrum of electromagnetic radiation — from ultraviolet to radio.) But that's unlikely, said Seth Shostak, an astronomer at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute.

"It was, in some sense, the most powerful message," Shostak told Live Science. "It's like a giant billboard on [U.S. interstate] I-5, but it's off in a field somewhere."

More recently, radio has been used to transmit everything from art to advertisements. In 2008, Doritos beamed its own ad to a solar system in the Ursa Majoris constellation, around 42 light-years away, according to the article in the International Journal of Astrobiology. In 2010, a message written in Klingon, a language used by fictional aliens in the "Star Trek" universe, invited real aliens to attend a Klingon opera in Holland.

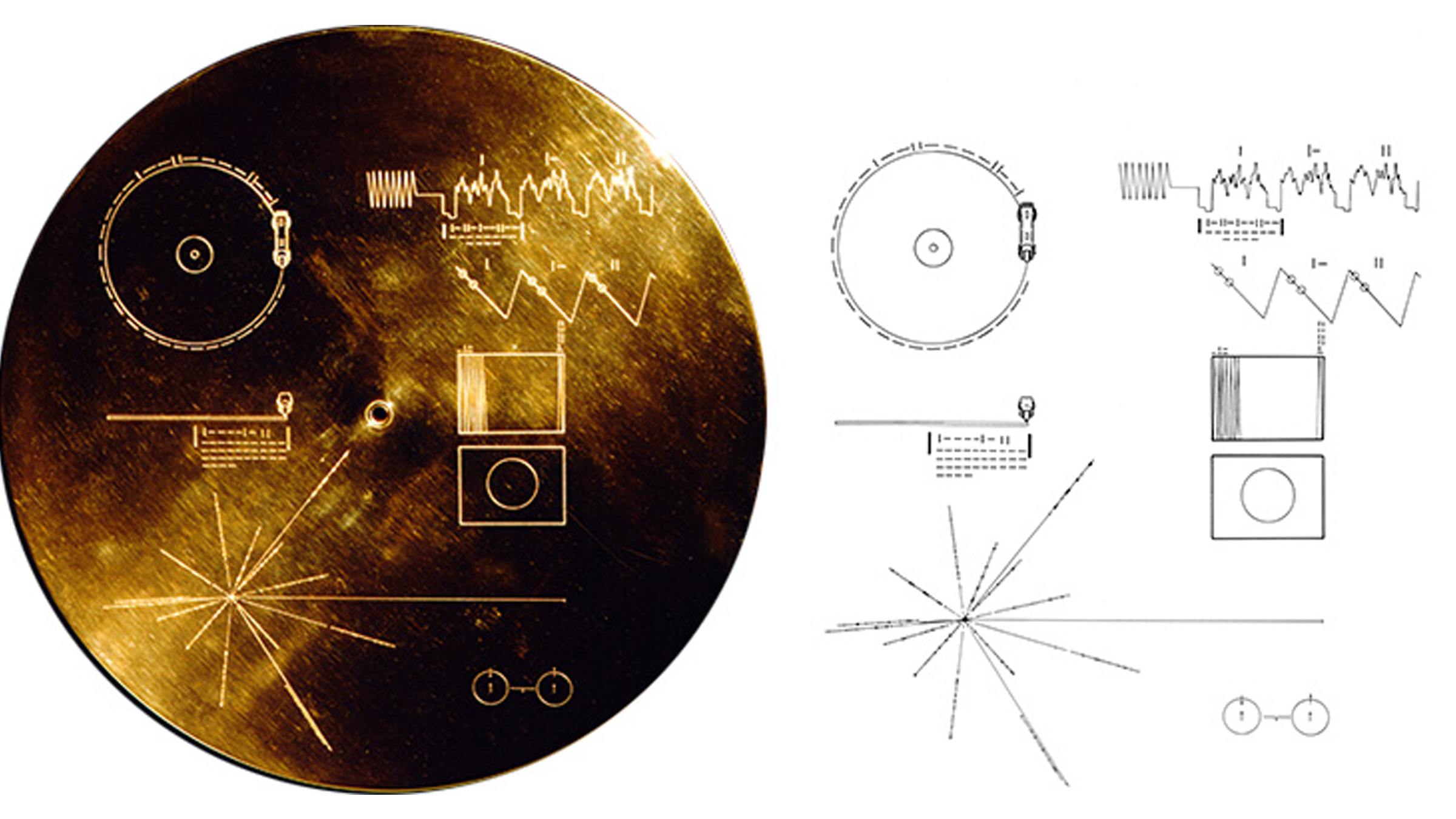

We haven't relied only on radio to communicate; we've also launched spacecraft containing artifacts from Earth, in the hope that they'll eventually be scooped out of interstellar space by intelligent life-forms. Voyagers 1 and 2 were launched in 1977 to explore the outer reaches of our solar system and interstellar space. Each carries a Golden Record containing music, ambient sounds from Earth and 116 images of our planet and solar system.

The Voyager spacecraft are still chugging through interstellar space, waiting to be discovered. But the chances of that happening? "Zero," said Sheri Wells-Jensen, a linguist at Bowling Green State University in Ohio who specializes in extraterrestrial intelligence.

"It was just a beautiful and poetic, lovely, brave attempt that really did sum up kind of the best of us, even if it's pointless in terms of actually communicating," Wells-Jensen told Live Science.

Experts agree that the likelihood that any of these attempts will reach alien civilizations is low. That outcome depends, of course, on whether there is alien life in our star system. But that life in question would also have to be listening closely for radio signals and understand enough about math and science to interpret our messages. Finally, the messages we've sent tend to assume that these aliens sense the universe in the same way we do: with hearing and vision.

But that doesn't mean all of these messages are pointless. "We're looking. Why wouldn't they be looking?" Wells-Jensen told Live Science. And if our messages are unintelligible to these hypothetical beings? That's OK. "I think the most important thing that we've ever said is just that we exist," Wells-Jensen said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Isobel Whitcomb is a contributing writer for Live Science who covers the environment, animals and health. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fatherly, Atlas Obscura, Hakai Magazine and Scholastic's Science World Magazine. Isobel's roots are in science. She studied biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, while working in two different labs and completing a fellowship at Crater Lake National Park. She completed her master's degree in journalism at NYU's Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon.