Could the Geminid meteor shower threaten satellites and astronauts on the International Space Station?

We examine whether meteor showers made from dust left by comets pose a hazard to satellites and the International Space Station.

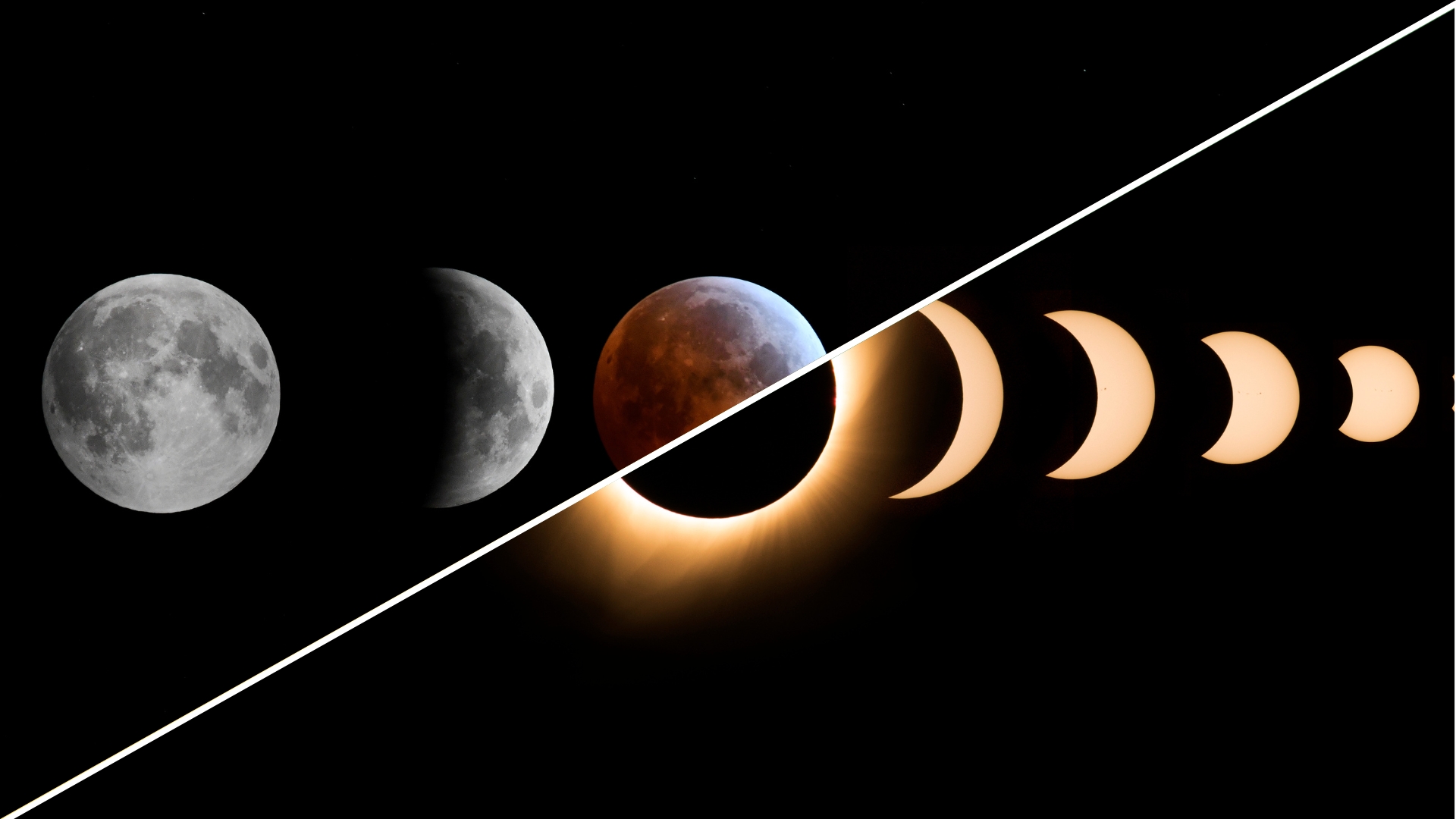

Meteor showers provide spectacular skywatching opportunities for observers on the ground as meteoroids — grains of cosmic dust left by comets — burn up, producing brilliant "shooting stars" as they enter Earth's atmosphere.

The next big meteor shower to grace our skies is the Geminid meteor shower which is expected to peak around Dec. 13.

But when a meteor shower douses Earth, does it pose any threat to satellites, spacecraft or astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS)?

In most cases, absolutely not, said Bill Cooke, head of NASA's Meteoroid Environment Office at Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama.

"If you are inside the ISS, meteoroids pose zero risk," Cooke told Space.com.

How the ISS is protected from meteoroids

Astronauts are protected from meteoroids because the ISS is equipped with a "Whipple bumper." Named after its inventor, Fred Whipple — who developed the "dirty snowball" model that describes the makeup of comets — the shield features sheets of metal with Kevlar between them. The shield doesn't deflect meteoroids, but it breaks them up, dispersing their energy into the shield.

"The odds of a meteoroid penetrating the space station are vanishingly small — you can think of the space station as the tank of low Earth orbit," Cooke said. "If you were an astronaut on EVA [extravehicular activity, i.e., a spacewalk] and you went outside the space station, you would see all these little pips and dents in the hull."

However, only about half of those dents are caused by meteoroid strikes. At the ISS' altitude of between 230 and 285 miles (370 to 460 kilometers), half of the impacts are caused by space junk instead, and occasionally, the ISS will have to maneuver to avoid space junk.

In fact, meteor showers pose hardly any problem to the ISS, according to Cooke. Statistically, it is the sporadic background of meteoroids — the bits of cosmic dust that are always there, unassociated with any shower — that contribute 90% to 95% of the danger, particularly to spacewalking astronauts who don't have that bumper shielding. That's why, before any spacewalk, Cooke's office issues a meteoroid forecast to ensure there is no heightened risk of an accident.

What are meteor storms?

The strongest annual meteor shower, the Geminids, which peak in December, poses only about 60% the risk of the sporadic background, according to Cooke. "Only during a meteor storm or outburst are the meteor rates significantly elevated," he said.

A meteor storm, or meteor outburst, is an amped-up meteor shower with potentially more than a thousand meteors visible in the sky per hour. Meteor showers occur when Earth passes through the trail of dust left by a comet. Earth encounters these various trails at the same points in its orbit each year, which is why each meteor shower occurs at the same time each year. However, we get a meteor storm when Earth passes through a denser patch of dust than usual.

Only a few meteor showers experience storms. The Leonids, which peak in November, have several consecutive years of storms spaced 33 years apart. The last Leonid storms were between 1998 and 2001, so the next are scheduled to occur in the early 2030s, when Earth will encounter that particularly dense clump of dust from comet Tempel-Tuttle.

Less predictable are the storms of the Draconid meteor shower, which peaks in October. Ordinarily, the Draconids provide a fairly drab spectacle, as they are composed of predominantly faint and slow-moving meteors, but in 1933, a Draconids storm resulted in 6,000 meteors per hour. The last storm, in 2018, produced a comparatively meager 150 meteors per hour.

Then, there's the Perseid meteor shower, which peaks in August and can randomly surge for a few hours; the most recent such outburst was in 2021.

Storms and outbursts are "batten-down-the-hatches types of deal," Cooke said. While the space station's bumper shield still protects astronauts inside, spacewalks are postponed and other satellites and spacecraft must take precautions. For example, the Hubble Space Telescope reorients itself so it is not looking at the meteor shower radiant (the direction the meteors are coming from). Cooke likened it to "the nuclear attack position, with your rear facing the radiant.'

The risk of meteor showers to satellites

The risk to any given satellite is minimal because individually, they have a small cross-section, a few tens of square meters. In comparison, the ISS' solar arrays alone span 114,000 square feet (10,600 square m), and even that is dwarfed by the huge expanse of the night sky.

"When I lay on my back, looking up at the night sky, I'm taking in roughly 30,000 square kilometers [12,000 square miles] of atmosphere that the meteors are burning up in," Cooke said. "Now compare that to tens of square meters. So the odds of a meteor hitting a satellite are small."

The risk is not zero, however. On rare occasions, satellites have been hit, although the only satellite ever to be permanently taken out by a meteor shower was an Olympus communications satellite during a Perseid outburst in 1993. A few others have recorded anomalies resulting from a small impact, and one or two have even been knocked on their side by a meteoroid strike.

"For example, an NOAA satellite was hit a few years ago, and that satellite kind of got bumped a little bit; it tilted forward so its camera was no longer looking at the Earth, and we had to get it back pointing the right way," Cooke said.

How you can help

The Meteoroid Environment Office's monitoring of meteor showers depends on observations from the ground, where meteor rates are counted, alerting scientists to any impromptu outbursts that could affect satellites or spacewalkers. Meteor observations can come from professional radar, such as the Canadian Meteor Orbit Radar, which is managed by researchers at the University of Western Ontario, and the Southern Argentina Agile Meteor Radar.

Amateur astronomers can also provide observations. For example, the Global Meteor Network consists of over a thousand cameras worldwide, while organizations such as the American Meteor Society, the UK Fireball Alliance, the British Astronomical Association and the International Meteor Organization all accept reports from amateur astronomers.

So, the next time you count shooting stars during a meteor shower, note how many you see, what time and date they occur, their color, how bright they are, and the direction in which they travel. Then, submit your report to one of the above organizations. Your observations could contribute to protecting a satellite or a spacewalking astronaut.

Overall, low Earth orbit is pretty safe from meteors.

"This notion of meteor showers being this swarm of debris that blows satellites to kingdom come — that's all Hollywood," Cooke said. "That never happens."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.