SpaceX rocket launches pioneering methane-tracking satellite to orbit

"Some call it the low-hanging fruit — I like to call it fruit lying on the ground."

A new satellite that will track climate-heating methane emissions from oil and gas companies around the world launched this week from California's Vandenberg Space Force Base.

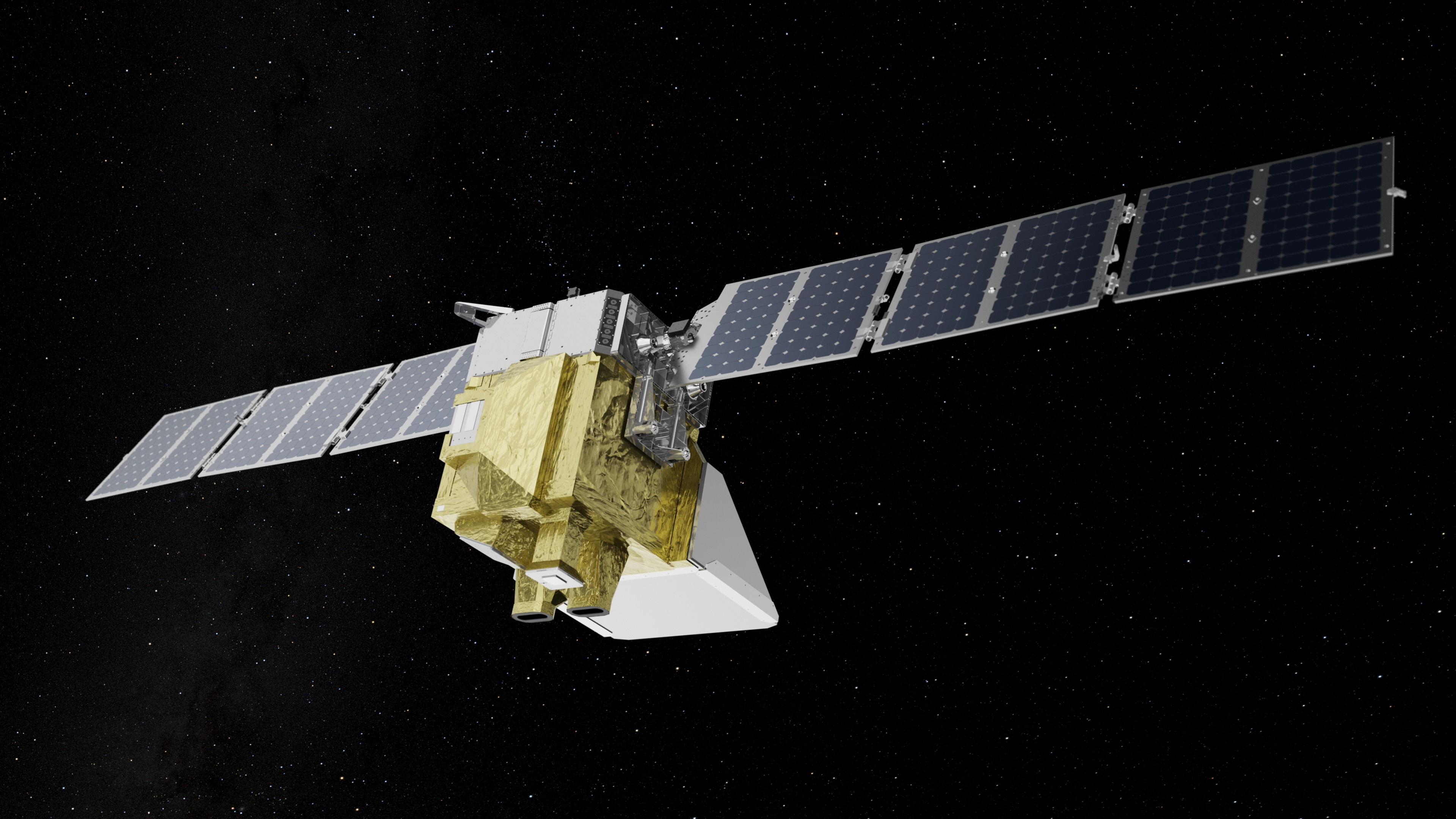

The washing-machine-sized satellite, named MethaneSAT, lifted off Monday (March 4) atop a Falcon 9 rocket, one of 53 payloads on SpaceX's Transporter-10 rideshare mission.

MethaneSAT is designed to ultimately help policymakers independently verify industry reports by pinpointing hotspots of methane, the invisible but potent greenhouse gas, which traps much more heat in Earth's atmosphere per molecule than carbon dioxide. MethaneSAT, the first satellite by a nonprofit environmental group, will collect data about methane leaks from 300 targets worldwide while circling Earth 15 times a day from its orbit 360 miles (580 kilometers) above ground, according to the mission plan.

"Having this data is really going to be the key to holding countries and companies accountable for methane pollution, and giving them the information they need to take action," Mark Brownstein, the senior vice president of energy transition at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) in New York, which built and is operating the satellite, said in a post on X prior to launch.

Related: Climate change: Causes and effects

Upon its release from the Falcon 9's upper stage on Monday, MethaneSAT deployed its solar panels and oriented itself toward the sun in order to charge its batteries, according to EDF.

Methane is the primary component of natural gas, which is burned during industrial activities in power plants and factories worldwide. An analysis by EDF found that U.S. natural gas pipelines leak anywhere between 1.2 million to 2.6 million tons of methane per year. Once methane escapes into the atmosphere as a result of such leaks, it behaves like a blanket, absorbing heat and reducing the rate at which it escapes into space.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Methane emissions have been overlooked and hard to detect for far too long," Kelly Levin, chief of science, data and systems change at the Bezos Earth Fund, one of the largest contributors to MethaneSAT, said in a statement on Monday. "MethaneSAT changes the equation, putting science and data front and center."

The satellite was developed for $88 million by EDF in partnership with the New Zealand Space Agency, Harvard University, British aerospace company BAE Systems and Google. Google will provide the MethaneSAT team with cloud computing services to process the satellite's data, while also helping improve EDF's database of oil and gas infrastructure, "so emission data for specific regions can be accurately attributed to verified facilities."

The first images from the satellite are expected in early summer and will be made publicly available later this year, EDF officials have said. This information could help companies, policymakers and governments more critically assess the progress being made to fight climate change.

"What we've learned over our decade of doing field measurements is that actually, when you measure actual emissions in the field, it turns out that the total magnitude of emissions coming from the industry is much higher than what's being reported by them using engineering calculations," Brownstein said in a press briefing on Friday (March 1), according to The Verge.

Along with industrial activities, sources of methane include landfills, agricultural activities and coal mining. In addition to collecting data from these sources, MethaneSAT will primarily focus on oil and gas companies due to their dominant share in global emissions as well as their tangible potential to reduce emissions.

"Some call it the low-hanging fruit," Steven Hamburg, EDF's chief scientist and MethaneSAT's project lead, said in a statement. "I like to call it fruit lying on the ground."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social