Physicists: Ancient life might have escaped Earth and journeyed to alien stars

A pair of researchers presented a wild new theory in a new paper.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A pair of Harvard astrophysicists have proposed a wild theory of how life might have spread through the universe.

Imagine this:

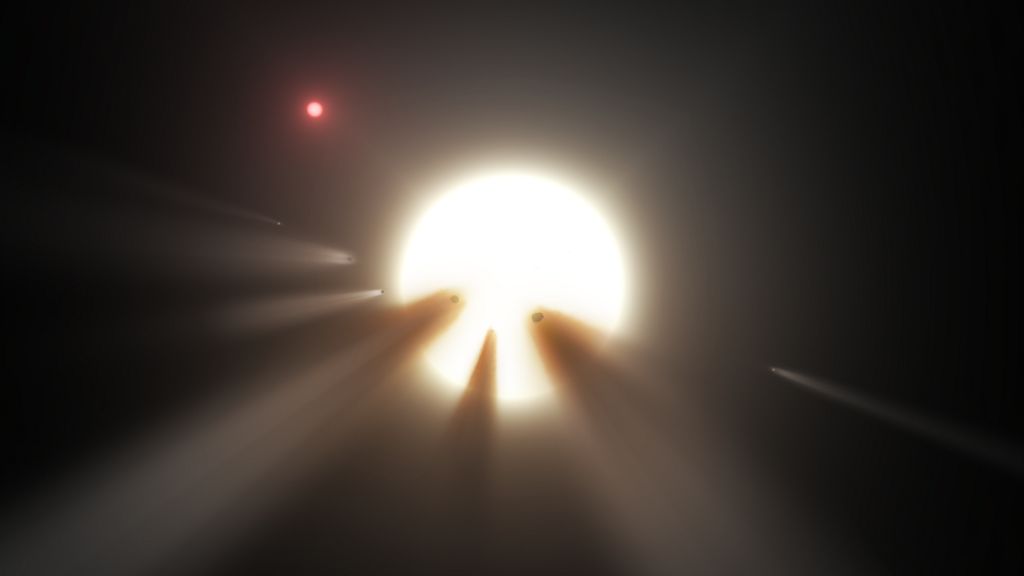

Millions or billions of years ago, back when the solar system was more crowded, a giant comet grazed the outer reaches of our atmosphere. It was moving fast, several tens of miles above the Earth's surface — too high to burn up as a fireball, but low enough that the atmosphere slowed it down a little bit. Extremely hardy microbes were floating up there in its path, and some of those bugs survived the collision with the ball of ice. These microbes ended up embedded deep within the comet's porous surface, protected from the radiation of deep space as the comet rocketed away from Earth and eventually out of the solar system entirely. Tens of thousands, maybe millions, of years passed before the comet ended up in another solar system with habitable planets. Eventually, the object crashed into one of those planets, deposited the microbes — a few of them still living — and set up a new outpost for earthly life in the universe.

Related: 5 Reasons to Care About Asteroids

You could call it "interstellar panspermia," the seeding of distant star systems with exported life.

We have no idea whether this ever actually happened –.and there's a mountain of reasons to be skeptical. But in a new paper, Amir Siraj and Avi Loeb, both astrophysicists at Harvard University, argue that at least the first part of this story — the depositing of the microbes into a comet that gets ejected from the solar system — should have happened between one and a few dozen times in Earth's history. Siraj told Live Science that although a lot more work needs to be done to back up the finding, it should be taken seriously — and that the paper may have been, if anything, too conservative in its estimate of the number of life-exporting events.

While the study's concept may seem far-fetched, humanity is constantly confronted with seeming impossibilities, like Earth going around the sun, or quantum physics, or bacteria hitching a ride into the galaxy aboard a comet — that turn out to be true, Siraj said

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And there's been reason to suspect that it might be possible. A series of experiments using small rockets in the 1970s found colonies of bacteria in the upper atmosphere. Comets really do enter and leave our solar system from time to time, and Siraj and Loeb's calculations show that it's plausible, maybe even likely, this has happened to large comets that graze Earth. Comets are porous, and might actually shield microbes from deadly radiation some microbes can survive a remarkably long time in space.

That alone is reason for scientists to take the idea seriously, Siraj said, and for researchers from fields like biology to jump in and figure out some of the details.

"It's a brand new field of science," he told Live Science

However, Stephen Kane, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Riverside, told Live Science that he was deeply skeptical of the suggestion that microbes from Earth might have actually turned up alive on alien planets through some version of this process.

The first problem would occur when the comet slammed into the atmosphere, he said. Siraj and Loeb point out that some bacteria can survive extraordinary accelerations. But the precise mechanism by which the microbes would adhere to the comet is unclear, Kane said, since the aerodynamic forces around the comet might make it impossible for any microbes to reach the surface and work their way deep enough below the surface to be protected from radiation.

It's also not clear, he said, whether any microbes would really have been up high in our atmosphere in the first place Those rocket experiments from the 1970s are old and questionable, he said, and we still don't have a good picture of what the biology of the upper atmosphere really looks like today — let alone hundreds of millions of years ago, when comet encounters were much more common.

The biggest question, though, Kane said, is what would happen to the microbes after they landed aboard the comet. It's plausible, he said, that some bacteria might survive decades in space — long enough to reach, say, Mars. But there's little direct evidence that any bacteria might survive the thousands or millions of years necessary to travel to another habitable star system. And that's really the key idea of this paper: Researchers have long suggested that debris from major collisions might blast life around between our solar system's planets and moons. But exporting life to an alien star system likely requires a more specialized scenario.

Still, Kane said, the calculations in this study of how precisely a comet might skim through the atmosphere were new to him, and "very interesting."

Siraj didn't strongly challenge any of Kane's concerns, but reframed them one by one as opportunities for further study. He wants to know, he said, precisely what the biology of the upper atmosphere looks like, and how comets might react to it. There's reason to think that at least some bacteria might survive super-long trips through deep space, he said, based on how robust they are under extreme conditions on Earth and in orbit. But for now, it's time for scientists across fields to jump in and start filling in the gaps, Saraj said.

- From Big Bang to Present: Snapshots of Our Universe Through Time

- The 11 Biggest Unanswered Questions About Dark Matter

- 5 Elusive Particles Beyond the Higgs

Originally published on Live Science.

Rafi wrote for Live Science from 2017 until 2021, when he became a technical writer for IBM Quantum. He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School of journalism. You can find his past science reporting at Inverse, Business Insider and Popular Science, and his past photojournalism on the Flash90 wire service and in the pages of The Courier Post of southern New Jersey.