This 3D Map of the Milky Way Is the Best View Yet of Our Galaxy's Warped, Twisted Shape

It's not flat like we thought.

By calculating the distance from the sun to thousands of pulsating stars across the Milky Way, astronomers have now charted our galaxy in 3D on a larger scale than ever before, a new study finds.

These new findings shed light on the warped, twisted shape of the galaxy's disk, researchers added.

The Milky Way is a spiral galaxy comprised of a bar-shaped core region surrounded by a flat disk of gas, dust and stars about 120,000 light-years wide. Our solar system is located about 27,000 light-years from the galactic center within one of the disk's four spiral arms. One light-year is the distance light travels in a year: about 6 trillion miles (10 trillion kilometers).

Related: Milky Way Quiz: Test Your Galaxy Smarts

A cosmic lighthouse

Much of the current knowledge regarding the shape and structure of the Milky Way is based on the distances between the sun and various celestial landmarks, informed by extrapolation from what astronomers have seen in other galaxies. However, the distances between the sun and these landmarks are usually measured indirectly.

In the new study, researchers sought to directly measure distances between the sun and a large sample of stars to help construct a 3D map of the galaxy. They focused on a specific kind of star known as a Cepheid variable.

Cepheids are young supergiant stars that burn up to hundreds of thousands of times brighter than the sun. Like lighthouses on foggy shores, Cepheids brighten and dim in predictable cycles and are visible through the vast clouds of interstellar dust that often obscure dimmer stars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cepheids appear to pulsate because their gas heats and cools, and expands and contracts, in very regular patterns that can last from hours to months. The well-defined link between a Cepheid's brightness and its pulsation schedule means that by timing its pulsations, astronomers can deduce how bright a Cepheid is intrinsically.

After comparing a Cepheid's intrinsic brightness to its apparent brightness — that is, how bright it appears from Earth — astronomers can then estimate the Cepheid's distance from our planet, given the knowledge that stars appear dimmer the farther away they are from us. Scientists can determine the distances to Cepheids with an accuracy better than 5%.

Related: Our Milky Way Galaxy: A Traveler's Guide (Infographic)

The Milky Way: A twisted, warped place

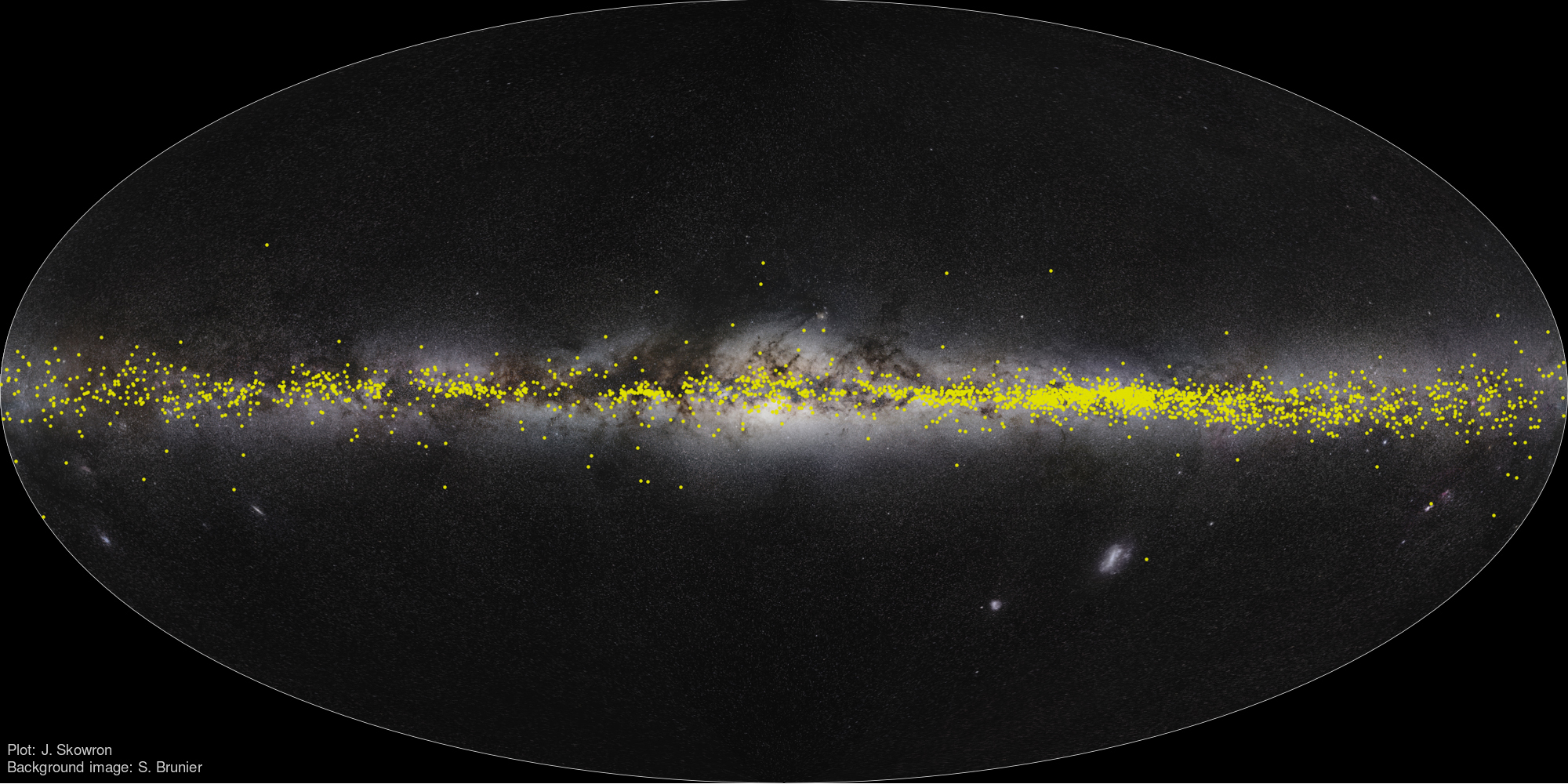

Using the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment, which monitors the brightness of nearly 2 billion stars, the scientists charted the distance between the sun and more than 2,400 Cepheids throughout the Milky Way. "This took six years but it was worth it," study lead author Dorota Skowron, an astrophysicist at the University of Warsaw in Poland, told Space.com.

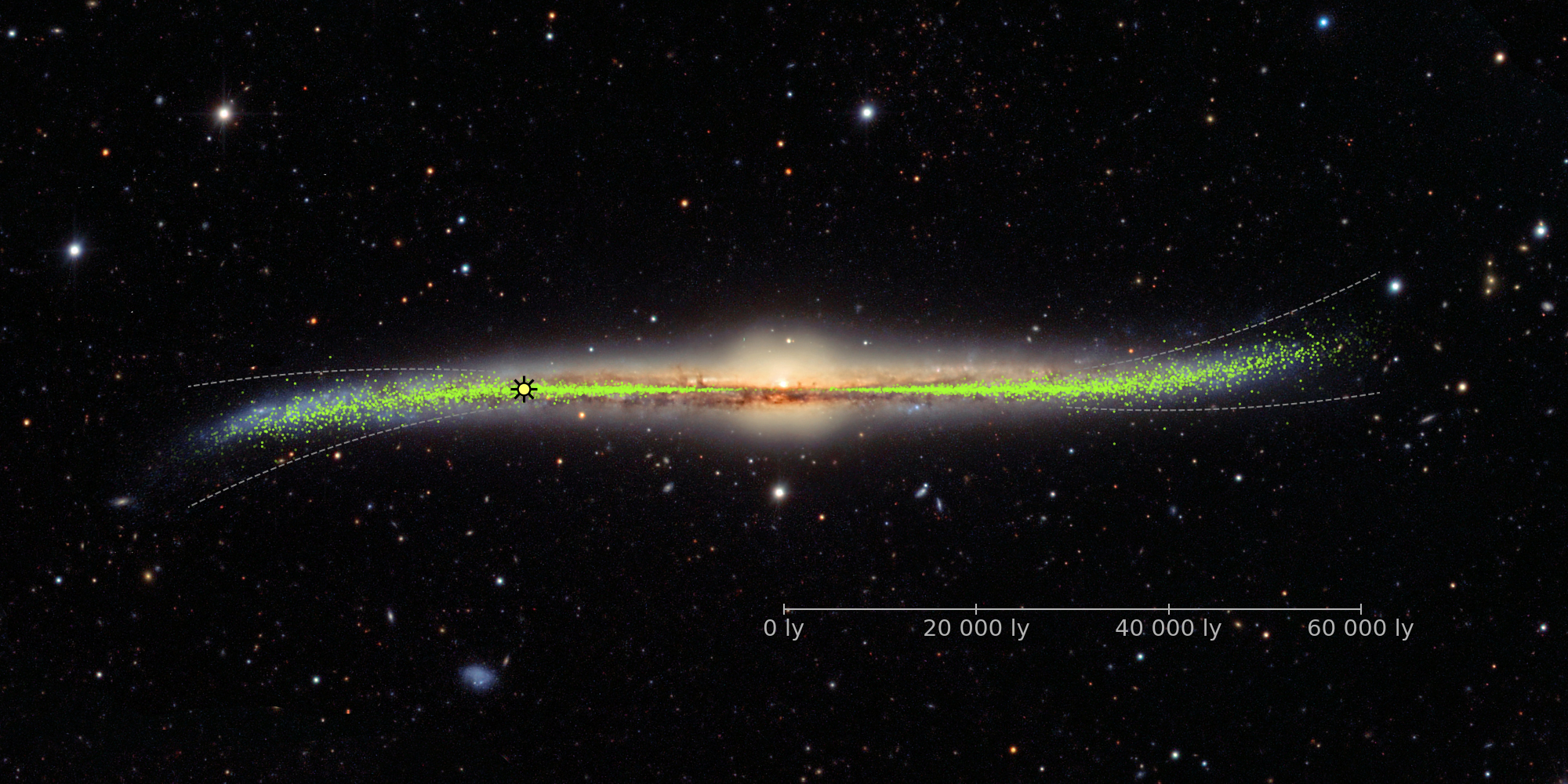

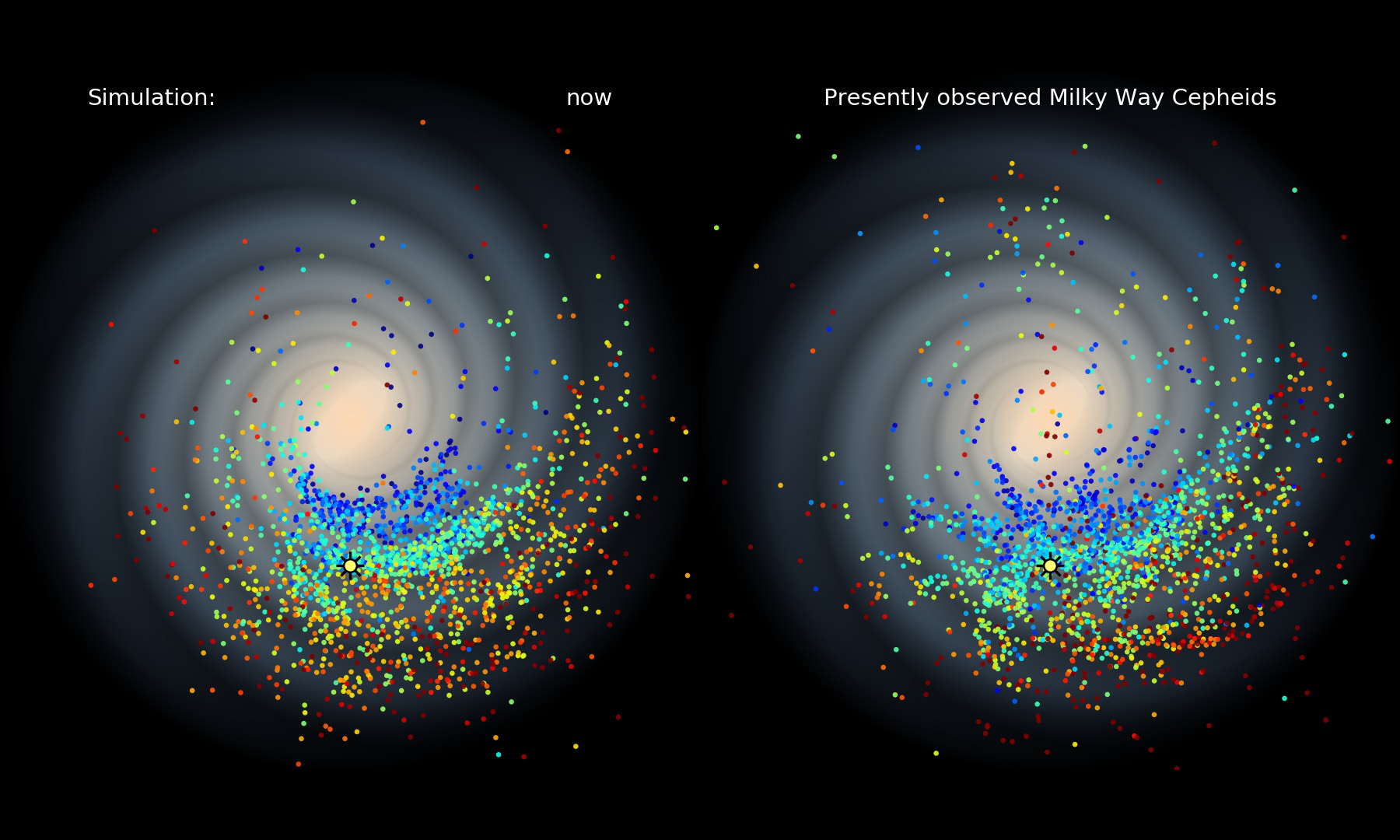

These findings helped the astronomers build a large-scale 3D map of the Milky Way. This is the first such map based on directly measured distances to thousands of celestial landmarks across the galaxy.

The new map helped reveal more details on distortions that astronomers had previously detected in the shape of the Milky Way. Specifically, the galaxy's disk is not flat at distances greater than 25,000 light-years from the galactic core, but warped. This warping was potentially caused by the galaxy's interactions with satellite galaxies, intergalactic gas or dark matter.

"Warping of the galactic disk has been detected before, but this is the first time we can use individual objects to trace its shape in three dimensions," study co-author Przemek Mróz at the University of Warsaw said in a statement.

The amount of warping the researchers saw in the Milky Way was surprisingly pronounced, Skowron said. "It is not some statistical fact available only to a scientist's understanding," she said. "It is apparent by eye."

Astronomers can deduce the age of Cepheids based on their patterns of pulsations. They found clusters of Cepheids with very similar ages.

"This is a clear indication that they were created together," Skowron said. "We can see with our own eyes and within our own galaxy that star formation is not constant but indeed is happening in bursts."

Stars might have formed in bursts due to a variety of triggers, Skowron said. Giant clouds of interstellar gas can fragment under their own gravity, collapsing into star-forming pockets. Titanic mergers between galaxies or interstellar winds from catastrophic supernovas can also have smashed clouds together into stars, she explained.

A better Milky Way map

In the future, the researchers plan to refine their 3D map of the Milky Way by charting the distances between the sun and other pulsating stars known as RR Lyrae. Like Cepheids, RR Lyrae pulsate in patterns with predictable spans of time, but they have existed in the galaxy for a much longer time, Skowron said. This would help scientists understand how the oldest parts of the galaxy have changed over time, she added.

Better 3D maps of the Milky Way can help scientists better understand its shape. For instance, "the number of the main spiral arms is still debated; also, the severity of the spiraling of the arms," Skowron said.

A better understanding of the galaxy's shape might then, in turn, shed light on how it has evolved over time, such as how stars move and spread from their birthplaces, what orbits stars take in the warped galaxy, and what exactly might have warped the galaxy's shape in the first place, Skowron added.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Aug. 2 issue of the journal Science.

- Get Ready for Milky Way Season with These Galactic Night-Sky Photos

- Pretty Panoramic Milky Way Photo Resembles an Astronaut's-Eye View

- The Universe Reveals Its True Colors in This Stunning Milky Way Photo

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us