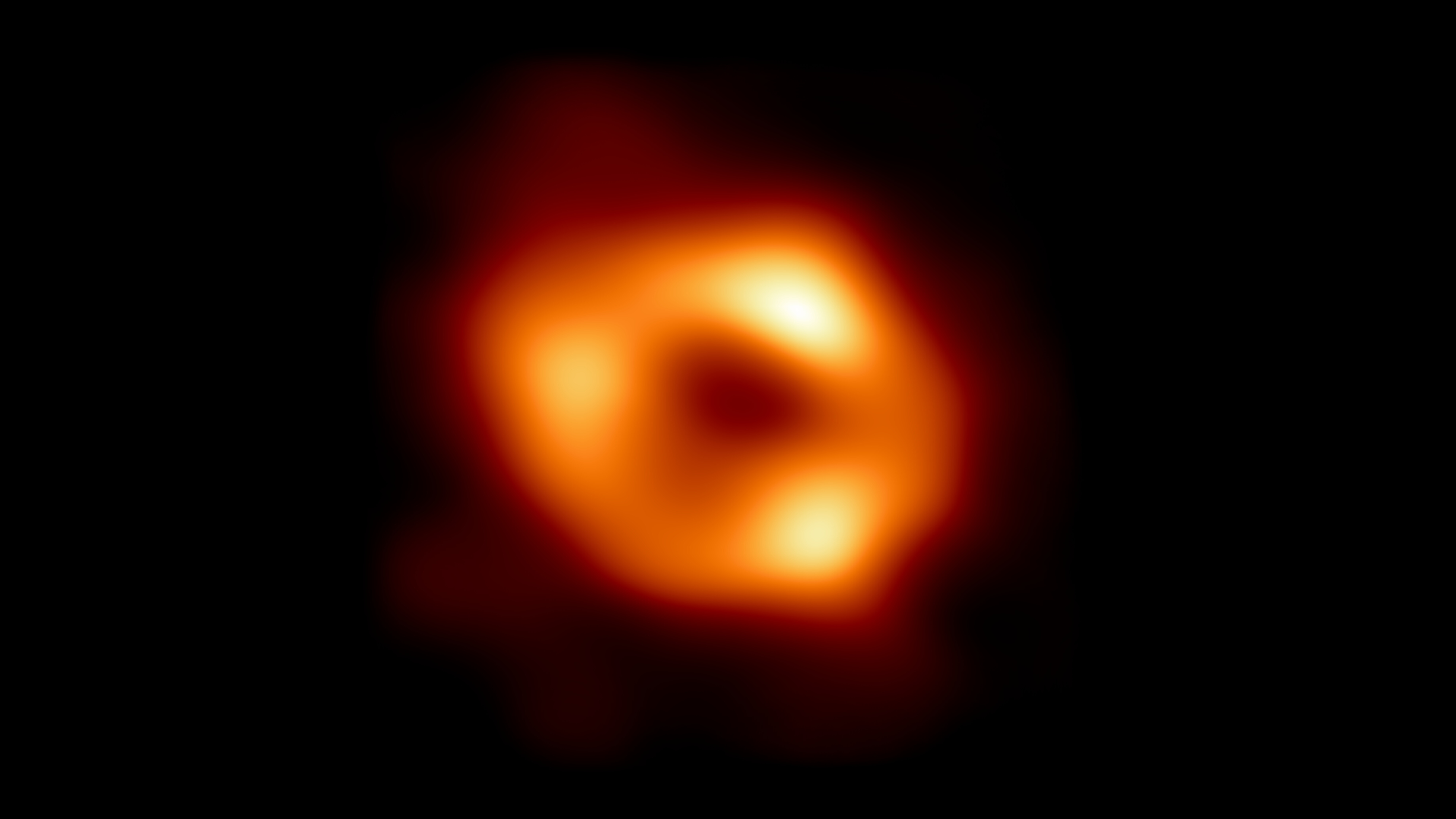

Yes, the new photo of the Milky Way's monster black hole looks fuzzy. Here's why it isn't.

It's actually one of the sharpest images ever.

Capturing the first-ever image of the Milky Way's black hole was no easy task.

The historic image released Thursday (May 12), of what scientists call Sagittarius A* took a planet-wide set of telescopes called the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT). The telescopes used atomic clock timing to fuse their data precisely, no easy task given that the material around Sagittarius A* the scientists were photographing changes shape every minute.

While the result still appears blurry to a non-specialist, scientists said this was because the collaboration was at the very edge of its abilities.

"We're pushing our instrument to its its limit here," Michael Johnson, an EHT team member who is also a Harvard and Smithsonian astrophysicist, told reporters during a news conference on Thursday. The image, he said, depicts the "finest features that it can see" because the telescope is at the diffraction limit, its limit of resolution.

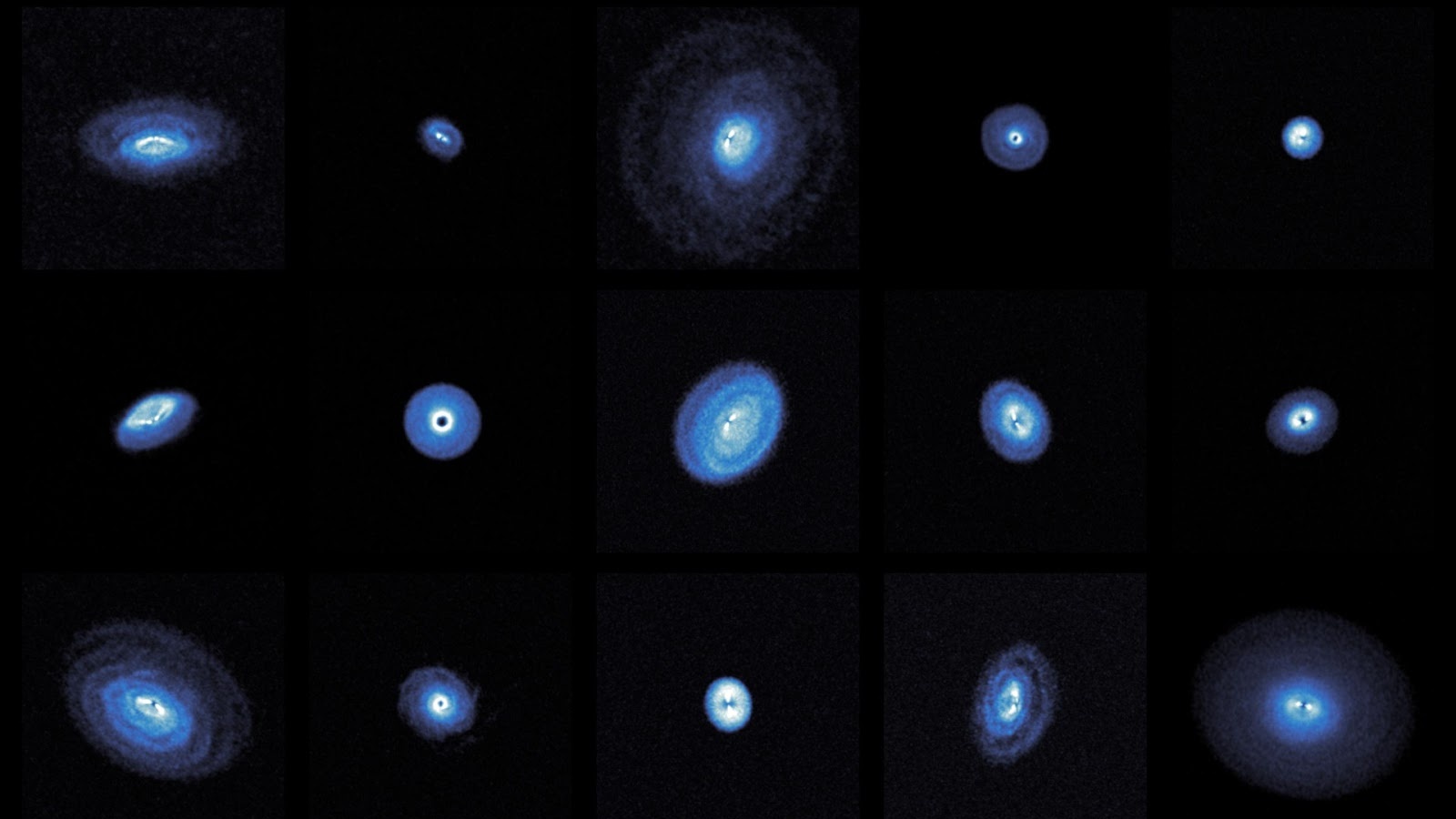

Related: Sagittarius A* in pictures: The 1st photo of the Milky Way's monster black hole explained in images

"To make a sharper image, we need to move our telescopes further apart ... or we need to go to higher frequencies," Johnson said, adding, "We're just at our breaking point here."

And because the Event Horizon Telescope is already an array the size of Earth, moving its observatories farther apart is quite a challenge. Scientists have talked about a space telescope array that could one day image black holes at wider distances from Earth orbit. But for today, the sharpness of the new Sagittarius A* image is as best as we can make it for now given the amount of data involved.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The images available publicly also don't reveal all the fine detail of the image's resolution, added team member Katherine Bouman, a computer scientist at the California Institute of Technology.

The original data, roughly 3.5 petabytes' worth (the equivalent of 100 million TikTok videos, according to EHT), had to be compressed and altered to fit standard public distribution channels online and through the media. So much data was involved that EHT investigators had to ship hard drives to one another for the science work, rather than streaming over the Internet.

"This image is actually one of the sharpest images you've ever seen," Bouman said. "It looks blurry on the screen because we only are seeing a few pixels, but actually, it's one of the sharpest images ever made."

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.