The Milky Way galaxy may be a different shape than we thought

The shape of our galaxy may reveal a history of collisions with other galaxies or even galactic clusters.

New measurements suggest that the Milky Way galaxy may have a different shape than we thought.

Over the past few years, astronomers have increasingly discovered that galaxies seem to come in three main shapes: Elliptical, irregular and spiral. The majority of known galaxies that fit in this last category seem to have two prominent "arms" that branch out and split into lesser arms.

But the traditional portrayal of the Milky Way is that of a galaxy with four major spiral arms extending out from a thick centralized bulge of stars. This makes our spiral galaxy stand out as an extremely rare outlier with an odd shape that must have some very unique properties to grant it four major arms.

That portrayal could be wrong, however. A team of astronomers has published new research that suggests we have been wrong about the shape of the Milky Way for decades, with our galaxy instead having two main arms just like its contemporary spiral galaxies.

Related: Milky Way galaxy: Everything you need to know about our cosmic neighborhood

The revelation that could reshape our understanding of the Milky Way came about when space scientists with the Chinese Academy of Sciences based at the Purple Mountain and National Astronomical Observatories analyzed multiple sources of astronomical data to get a better understanding of our galaxy's true shape.

"In spite of much work, the overall spiral structure morphology of the Milky Way remains somewhat uncertain," the astronomers wrote in a paper describing their research and conclusions. "In the last two decades, accurate distance measurements have provided us with an opportunity to solve this issue."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

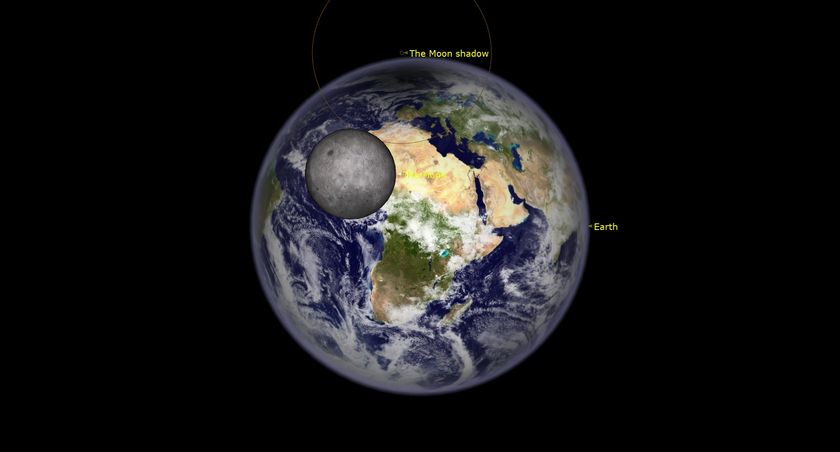

The team assessed data from a new generation of space instruments that can better measure the distance to individual stars which allowed them to measure the distances to around 200 stars and start putting together a map of the Milky Way. They then added data from the European Space Agency (ESA)'s Gaia space telescope which precisely observes the movement of stars and their location in relation to Earth.

In particular, the astronomers honed in on hot and massive stars called OB stars in the Gaia data. Because these stars are short-lived they move very little during their main-sequence hydrogen-burning lifetime which makes them useful for mapping purposes. Data collected from 24,000 OB stars was added to the map as were Gaia observations of over 1,000 open galactic clusters.

This led the astronomers to suggest that the Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy with just two main arms extending from this dense central bar.

"Using the precise locations of very young objects, for the first time, we propose that our galaxy has a multiple-arm morphology that consists of two-arm symmetry," they wrote. "The Norma and Perseus Arms are likely the two symmetric arms in the inner Milky Way. As they extend from the inner galaxy to the outer parts, they bifurcate, and connect to the Centaurus and Sagittarius Arms, respectively."

At the outskirts of the Milky Way, the astronomers write, are distant and fragmented irregular arms that are not connected to the central bulge of the galaxy where the majority of its stars are located. The fragmentation of spiral arms may have been caused by our galaxy colliding with other galaxies or even galactic clusters in its ancient history.

The team of astronomers concluded that this new model of the Milky Way's shape could provide an alternative basis for future studies of galactic structure. They add that more details should be revealed by further observations of nearby radio sources taken by multiple telescopes that would allow their distances from Earth to be calculated, and by improved data from the Gaia spacecraft. Gaia launched in 2013 and is expected to observe the universe for at least another two years until 2025.

The team's research is published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

Marc2001 We don't know what our galaxy actually looks like because WE ARE INSIDE OF IT!!!!!! The only way we'll ever determine the shape of the Milky Way is to observe it from intergalactic space, And to get there, we are going to have wait until the far, far, far distant future at which point we'll be able to travel at light years per second to get to some point far away enough to really see it.Reply -

billslugg Or we could measure he distance and direction of a lot of stars and make a model of the Milky Way. Then we could look at the model and see what shape it is.Reply -

murgatroyd Reply

Speed of light is the speed limit in this universe, so on first glance your prediction cannot come to pass. However, perhaps the definition of "second" changes in the future. Our descendants may opt for immortality or extreme longevity and combine this with a corresponding lengthening of the shortest interval of perception. Then, what we see as a million years, feels to them like a mere second.Marc2001 said:we are going to have wait until the far, far, far distant future at which point we'll be able to travel at light years per second .

Upside of that change is they need not fear the soul-killing boredom of interstellar travel. All the beautiful stellar formations, quasars, supernovas imaged by Hubble are now within a day's outing (a "day" on their timescale). Downside, they lose all ability to communicate with short-lived beings like us. -

Pogo That is one of the hardest things to do, determining the shape and characteristics of the Milky Way from within, especially as stars in some directions can’t be seen or measured due to intervening dust and gas. Like determining the shape of a forest from inside.Reply -

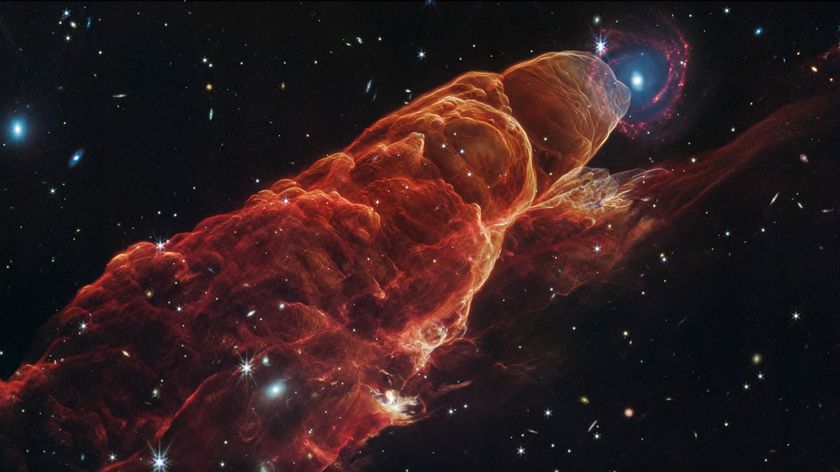

billslugg Yes, Webb can see with wavelengths up to 28 microns. It can go through dust any smaller than that without hardly any attenuation. Any dust bigger than that is extremely rare in interstellar space. It should be able to see stars on the far side of our galaxy. They just need some time to do the observations. Thousands are required to show the shape of our galaxy. This would be a fairly low priority for them. Such a study does not need to look at specific locations. They can get their data by piggybacking on whatever observations are being done. They will be randomly scattered around the sky. Over a 1 year period, the whole sky is visible to JWST.Reply