Milky Way vs M87: Event Horizon Telescope photos show 2 very different monster black holes

'M87 was exciting because it was extraordinary. Sagittarius A* is exciting because it's common.'

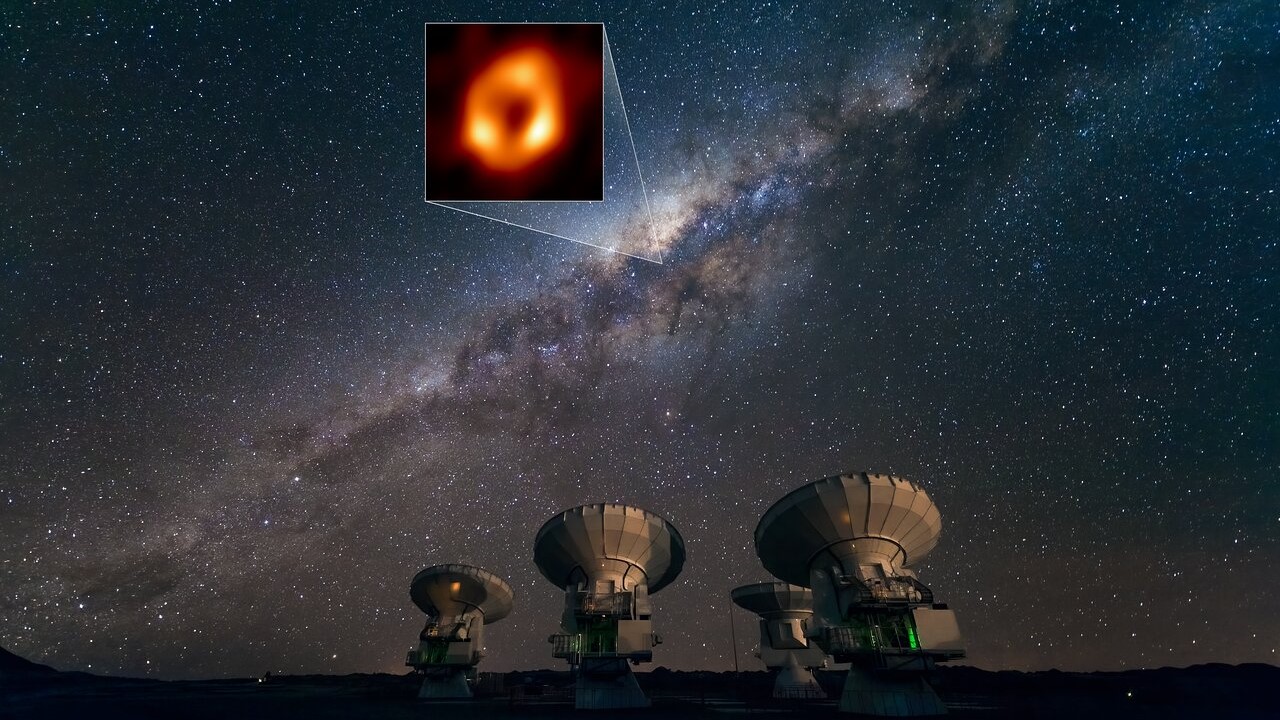

Three years ago, scientists used a telescope the size of Earth to produce the first-ever image of a black hole. Now, they've done it again — this time, closer to home, and of a very different invisible behemoth.

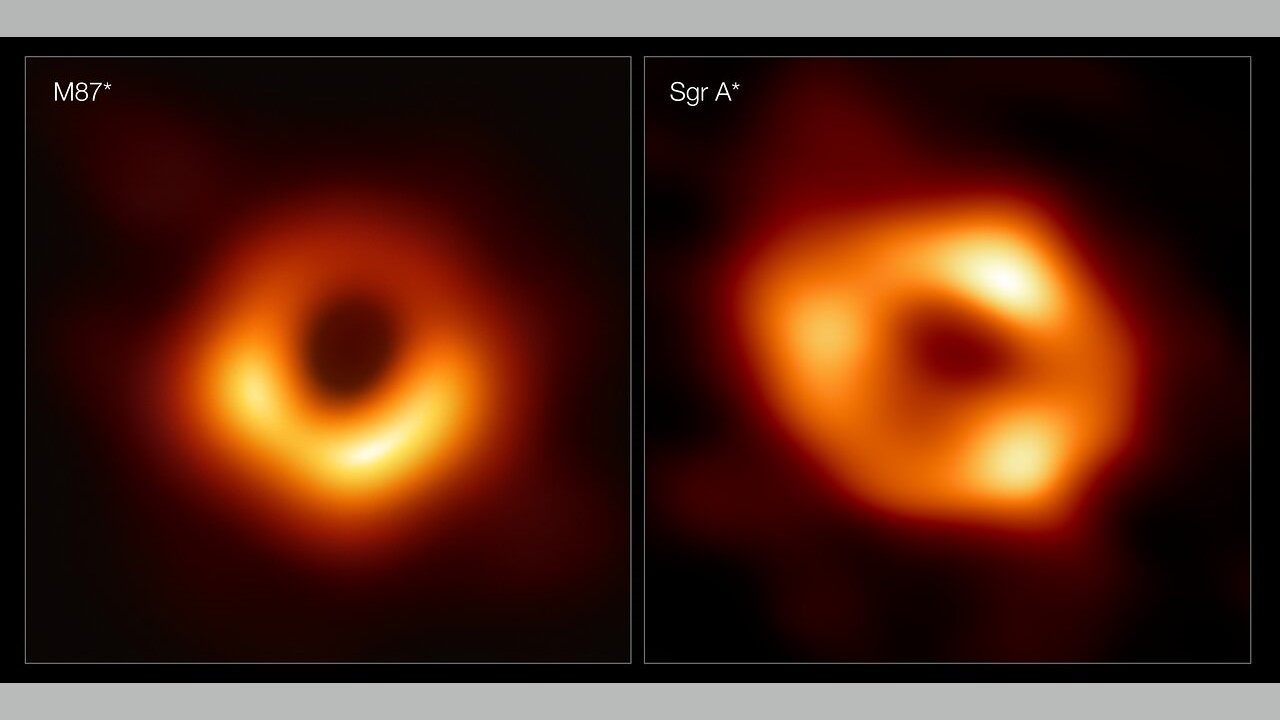

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) has now produced images of two supermassive black holes: the one in the center of a galaxy called M87 and the one at the center of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. In the process, the hundreds of scientists involved in the endeavor have gotten their first glimpses of two objects with surprisingly little in common.

"The two images appear very similar to us when we gaze at them in the sky," Feryal Özel, an astrophysicist at the University of Arizona and a member of EHT's science council, said during a news conference held by the National Science Foundation on Thursday (May 12) to unveil the new image of Sagittarius A* in the Milky Way. "But the two black holes couldn't have been more different from each other in practically every other way."

Sagittarius A* in photos: The Milky Way's monster black hole discovery in images

In particular, the two black holes differ in how difficult it is to image material moving around its boundary, or event horizon. (That material, which glows as it is consumed, is what lights up the fuzzy rings the EHT has labored to produce, since black holes themselves don't emit any light.)

Sensibly, the EHT tackled the less challenging target first. That's the monster hiding within M87, also known as M87*. This black hole is farther away from Earth, of course, but it's also much larger, and material moves around its event horizon at a more leisurely pace.

"Material swirls around M87* over the course of many days," Vincent Fish, an astrophysicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Haystack Observatory and a member of EHT's science council, said during the news conference. "It sits still for its photograph."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Milky Way's supermassive black hole, dubbed Sagittarius A*, is less cooperative. "It takes only a few minutes for material to move around close to the horizon of Sagittarius A* because it is much smaller," Fish added. "It changes quickly, so we had to collect our data quickly."

Related: 8 ways we know that black holes really do exist

And the challenge of Sagittarius A* was evident as scientists analyzed the data the EHT gathered as well. Katie Bouman, a computer scientist at the California Institute of Technology and co-lead of the EHT Imaging Working Group, said during the news conference that when the independent imaging teams that formed to analyze the M87* results compared their first takes at an image, they were more or less the same.

Not so for the second black hole. "Imaging Sagittarius A* was a bit of a messier story than imaging M87*," Bouman said. This time, the imaging groups were reluctant to produce an initial image because there was so much less consensus among team members.

Although the material surrounding Sagittarius A* is moving around the event horizon inconveniently fast, our supermassive black hole nonetheless offers a much tamer environment near its surface than M87* does. The turbulence in this region is determined by the black hole's appetite, which varies despite the popular conception that all black holes guzzle with the suction of a cosmic vacuum cleaner.

"If Sagittarius A* were a person, it would consume a single grain of rice every million years," Michael Johnson, an astrophysicist at the Harvard/Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and member of the EHT science council, said during the news conference. "Only a trickle of material is actually making it all the way to the black hole."

Growing at that slow a pace, Sagittarius A* is quite the dainty eater. "Because of that, its environment is relatively gentle," Özel said. "When we say that, of course, the temperatures and magnetic field strengths are still quite high, and the motion of gas around it is still turbulent."

But while Sagittarius A* was the more difficult target for EHT scientists to study, it was also an important challenge to tackle, the scientists said. "Sagittarius A* is giving us a view into the much more standard state of black holes: quiet and quiescent," Johnson said. "M87 was exciting because it was extraordinary. Sagittarius A* is exciting because it's common."

Yet despite all the differences, at a glance, the new portrait of Sagittarius A* might even be mistaken for the iconic image released in 2019.

"When we look at the heart of each black hole, we find a bright ring surrounding the black hole shadow," Özel said. "These two images look similar because they are the consequence of fundamental forces of gravity."

That's physics, although it's still tempting to have fun with the similarity. "Space-time, the fabric of the universe, wraps around black holes in exactly the same way, regardless of their mass or what surrounds them," Özel said. "It seems that black holes like doughnuts."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.