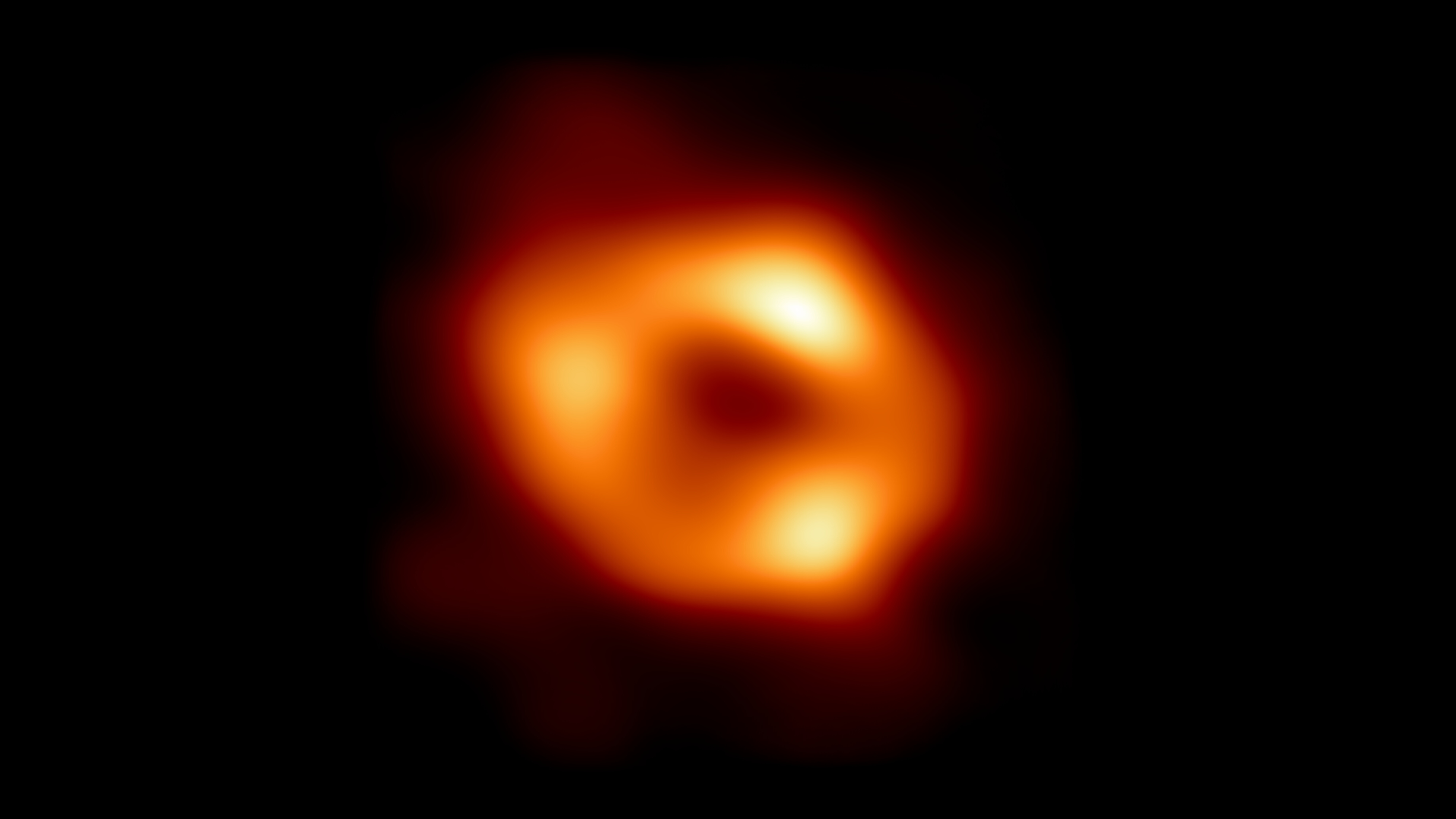

Behold! This is the first photo of the Milky Way's monster black hole Sagittarius A*

Say hello to Sagittarius A*.

The Event Horizon Telescope has captured a historic first image of the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy.

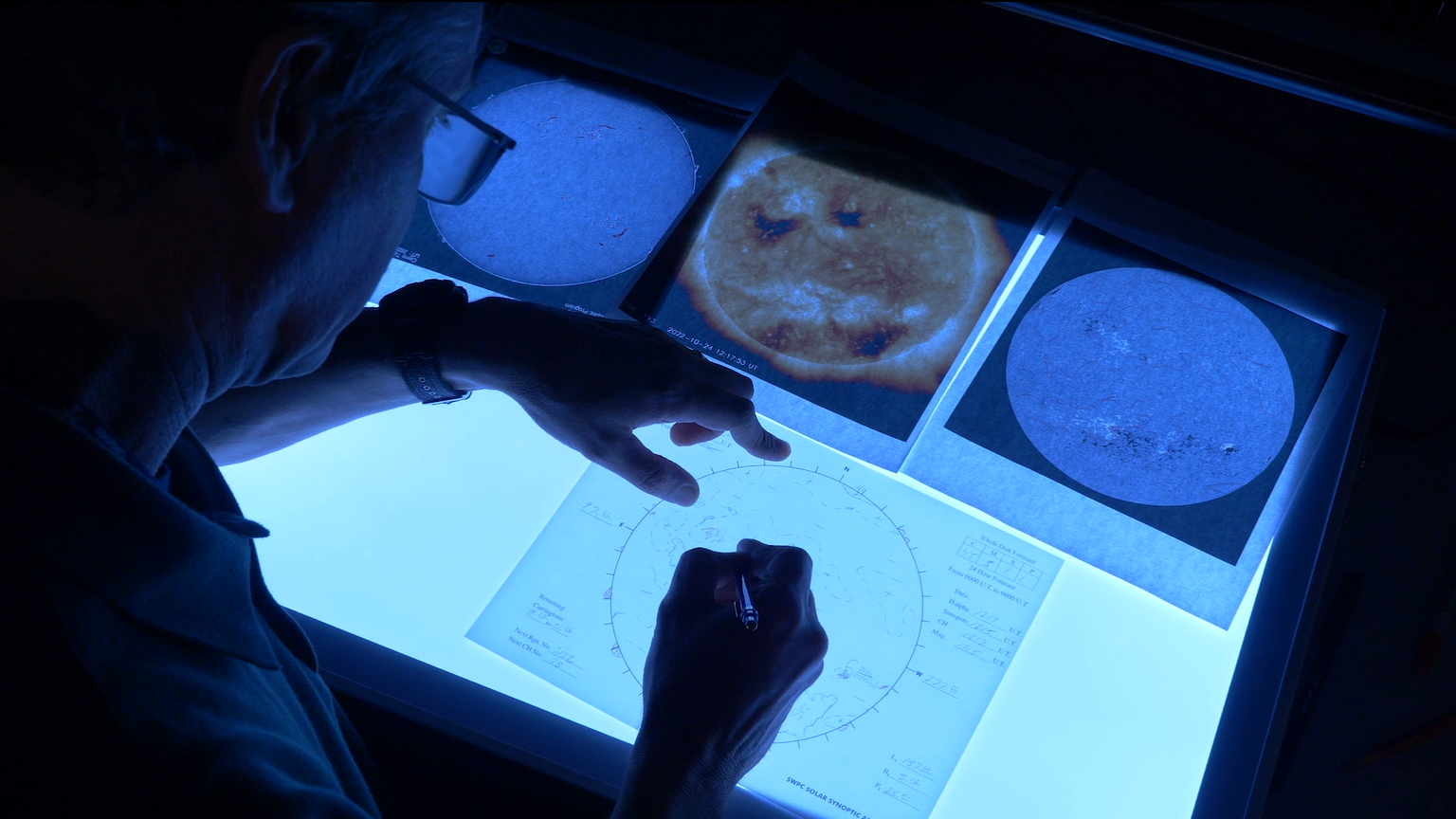

The image, which was taken in the light of submillimeter radio waves, confirms that there is a black hole in the heart of the Milky Way that is feeding on a trickle of hydrogen gas.

"Until now, we didn't have the direct picture to prove that this gentle giant in the center of our galaxy is a black hole," Feryal Özel, an astrophysicist at the University of Arizona, said during a National Science Foundation news conference held Thursday (May 12). "It shows a bright ring surrounding the darkness, and the telltale sign of the shadow of the black hole."

Related: Here's how scientists turned the world into a telescope (to see a black hole)

"This is an astounding achievement," Ryan Hickox, an astrophysicist at Dartmouth College who is not a member of the EHT team, told Space.com. "I think I speak for a large number of my astronomy colleagues when I say how remarkably grateful we are."

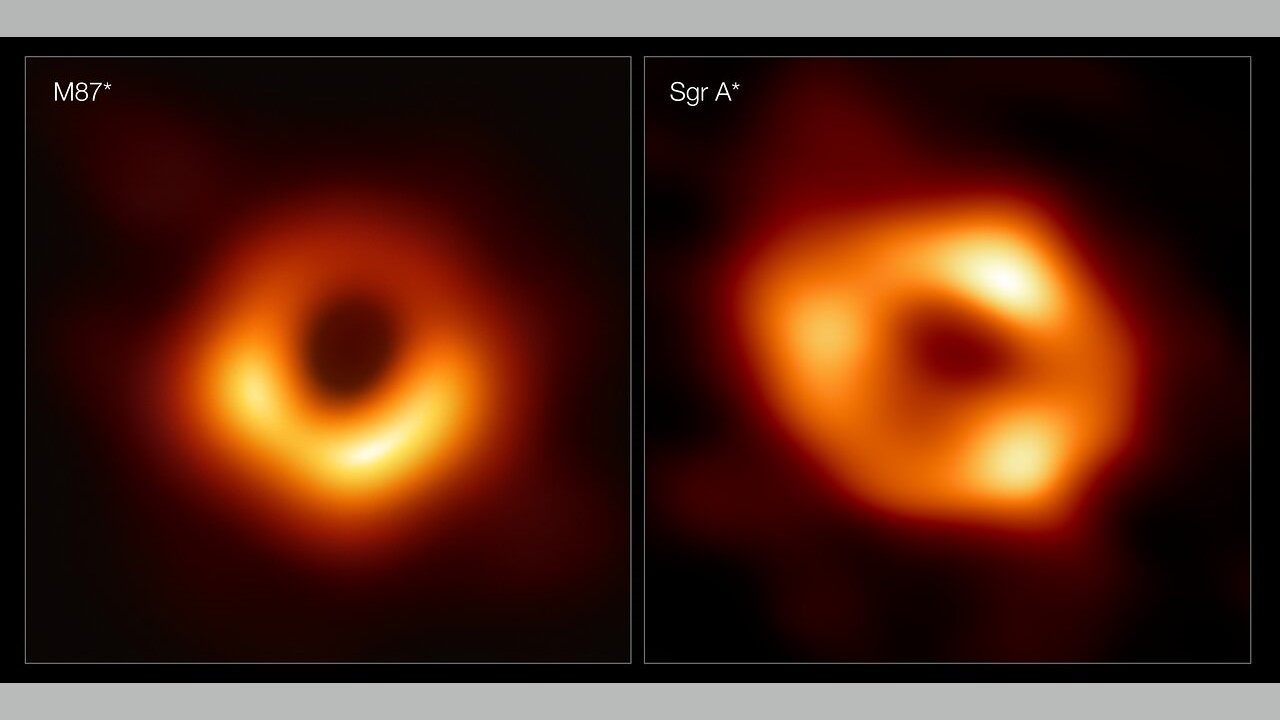

In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) made headlines when it succeeded in producing the first ever image of the event horizon of a black hole, specifically the black hole at the center of the active elliptical galaxy Messier 87. At the same time as it gathered the data that became that image, the EHT also performed observations of Sagittarius A*, which is the name given to the Milky Way's supermassive black hole. However, producing an image of Sagittarius A* proved more difficult than for M87.

For one thing, Earth's water-laden atmosphere can absorb the submillimeter radio waves that the EHT relies on. Moreover, gas and dust in the intervening 27,000 light-years between us and Sagittarius A* can scatter the submillimeter waves and blur the image. Lastly, whereas M87's black hole has a voracious appetite and appears bright because it is consuming a lot of gas, the flow of material onto Sagittarius A* is far more feeble, meaning it is much fainter.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Getting to this image wasn't an easy journey," Özel said. "It took several years to refine the image and confirm what he had."

Black holes are the densest objects in the universe, and their gravity is irresistible, to the extent that within a certain distance of a black hole, not even light can escape. Scientists call this "point of no return" the event horizon.

The EHT is able to see light, in the form of radio waves, from hot gas swirling around the edge of the event horizon. The black hole feeds from the material within its immediate environment, whether gas clouds, asteroids or even stars that might wander too close and be ripped apart by gravitational tides.

However, Sagittarius A* is being starved.

"We only see a trickle of material making it all the way to the black hole," Harvard astrophysicist Michael Johnson said during the NSF press conference. "In human terms, it would be like eating just one grain of rice every million years."

Why the accretion of gas onto Sagittarius A* is so slow has been a puzzle for many years, Nobel Prize laureate Andrea Ghez, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Los Angeles, told Space.com. "There's a lot of mysteries associated with the accretion flow, in terms of why it is so faint," she added.

Ghez shared the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics for measuring the mass of Sagittarius A* by observing the motions of stars orbiting close to it. Ghez and her team calculated a mass that was 4.3 million times the mass of our sun.

Since the size of the event horizon is connected to the mass of the black hole, it was therefore possible to make a prediction, Ghez said. "The power of imaging the black hole's ring is that, if you know the mass and distance to the black hole — in other words, the size of the event horizon — then you can use that to compare to theory."

The new image shows that the size of Sagittarius A*'s event horizon is 51.8 microarcseconds on the sky.

"Our image is in very close agreement with theoretical predictions," said Özel, who described it as the biggest test of Einstein's theory of general relativity ever made, noting that the theory passed with flying colors.

"It's a great laboratory for trying to understand how gravity works in the vicinity of a supermassive black hole," Ghez said.

More uncertain are our explanations for the turbulence seen in the gas ring. The black hole of M87 is much larger than Sagittarius A*, and therefore it takes days for changes to become apparent, whereas Sagittarius A* is much smaller and, as material whips around it, the brightness of the ring can change in mere minutes.

"It is teeming with activity, always gurgling with turbulent energy," Johnson said of the ring around the event horizon.

To try to explain what they were seeing, the EHT team — which is made up of more than 300 researchers across 80 institutions — performed more than 5 million supercomputer simulations to try and find one that was a match for what they observed.

"We were left with only a handful of simulations that share the features that we observe, but none of them explain all the features," Johnson said. In particular, the simulations all predicted more and faster variability than what was actually seen, and could relate to how gas is accreting onto the ring, or how magnetic fields are interacting with that inflow.

Reacting to the image, Hickox said that "it's just remarkable to see an image of the black hole that we know best, and to see the ring and measure the shadow size as accurately as they did."

Furthermore, this image of Sagittarius A* can now act as a template for other quiescent black holes in the universe.

"This black hole is more typical of the overall set of black holes in the universe than the one in M87," Hickox said. “If you were just to take a picture of a random supermassive black hole in a galaxy somewhere in the universe, then this is what it would look like."

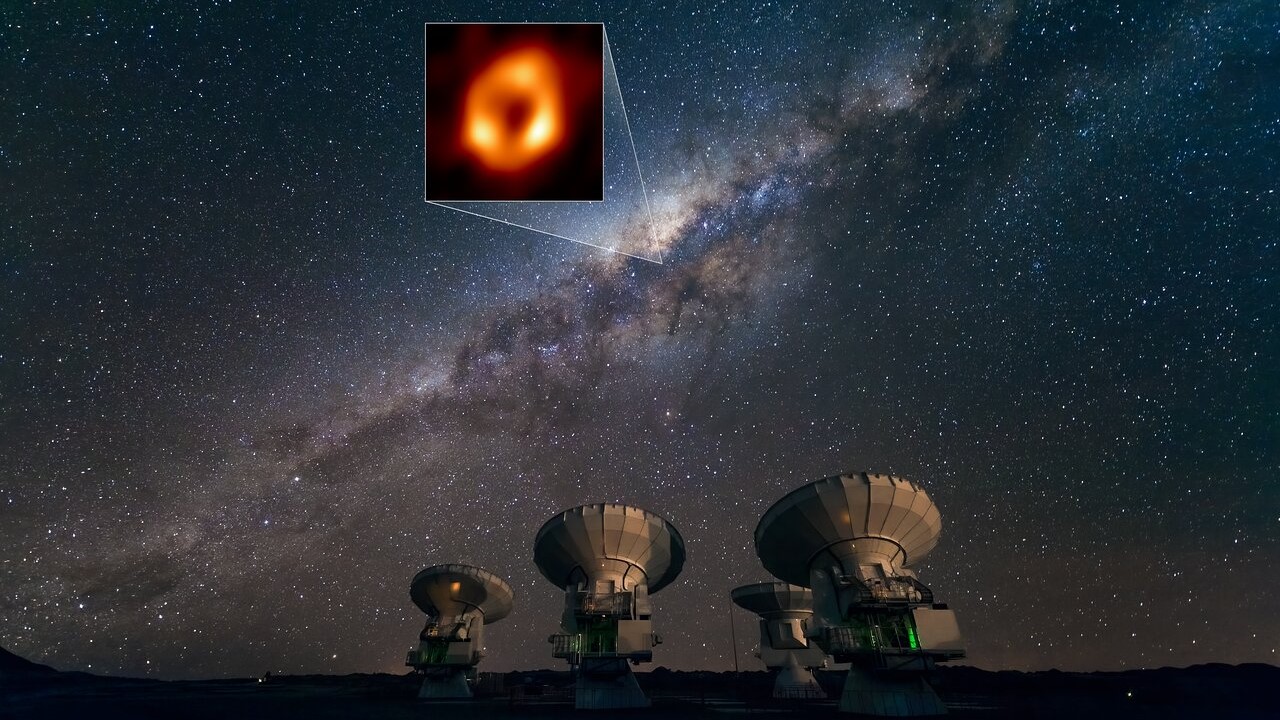

This image of Sagittarius A*, and of the black hole in M87 before it, has been made possible through the magic of a technique known as Very Long Baseline Interferometry, which allows astronomers to combine data from radio telescopes all across the world as though they were one large telescope, effectively making the EHT the largest telescope on Earth.

At the time when the observations were made, the network consisted of eight telescopes (including one, the South Polar Telescope, that was too far south to study M87), although three more have since been added to the network. The eight-telescope configuration means that the EHT's maximum baseline — which is equivalent to a telescope's aperture — for observing Sagittarius A* was 6,650 miles (10,700 kilometers) across.

Future observations will now focus on getting sharper images to better understand the physics of turbulence in the ring around the black hole, as well as how the black hole affects the environment of the galaxy around it.

"This is driving us to make even better measurements and sharper images," Johnson said.

Sagittarius A* and the black hole in M87 were the EHT's top two targets because of their relatively large angular size on the sky. Supermassive black holes in other galaxies appear far smaller on the sky, beyond even the abilities of the EHT to image their event horizon. To be able to do so would require a lengthening of the baseline — that is, to widen the EHT's aperture — between the two widest points in the EHT's network. In this sense, the resolution that the EHT can achieve is limited by the size of Earth, but Hickox says there are possibilities beyond Earth.

"I've heard talk about potentially having a space-based addition to the EHT, which would significantly increase the overall angular resolution," he told Space.com. "That would be an exciting step forward."

Editor's note: This story was updated at 10:45 a.m. and 1:20 p.m. ET to include additional information about the finding. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.