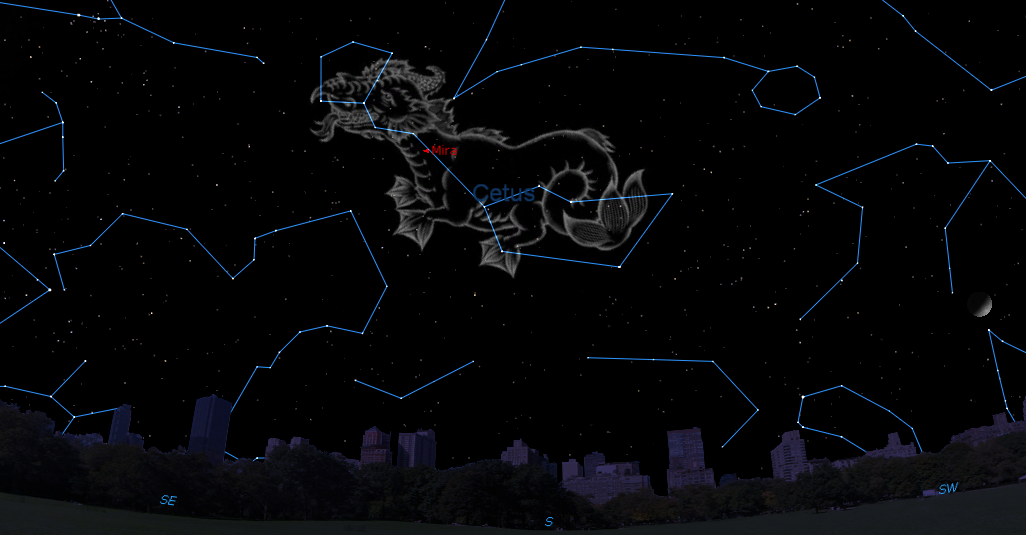

This week, the variable star Mira reaches its highest point, roughly halfway up in the southern sky at around 10 p.m. local time.

Although now nearly a month past maximum brightness, it should still be bright enough to see without a telescope. Try looking for it the first clear night this week.

Some classes of stars deserve special attention. One such class is variable stars, which can appear to brighten and fade at both regular and irregular intervals.

Related: How to Tell Star Types Apart (Infographic)

Variable stars fall into two basic categories: eclipsing stars and intrinsic variables.

Eclipsing stars are variable star systems in which one star crosses partially or completely in front of another, causing an apparent dimming of starlight as seen from Earth. One example of an eclipsing binary is the star Algol, in the constellation Perseus.

Intrinsic variables are stars whose light changes are inherent in the fundamental structure of the stars. Such stars can fluctuate physically in their color, spectrum, and effective temperature and heat output. In addition, the radial velocity of such stars as they travel through space can change due to their rate of convection, expansion and contraction.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The vast majority of intrinsic variables are periodic or almost periodic in their variability, but many can vary unpredictably, often for reasons we do not fully understand.

One of the most famous examples of this type is the long-period variable star Mira — the first variable star to be discovered.

Mira is located in the constellation Cetus, known by the ancient Greeks as the monster that was about to attack Andromeda when the hero Perseus arrived just in time to destroy it. Cetus was later thought to represent the whale that devoured Jonah. Cetus consists mostly of dim stars, but it occupies a large area of the sky.

Now you see it ... now you don't!

In August 1596, David Fabricius (1564-1617), a German pastor and skilled amateur astronomer, discovered a third-magnitude star in Cetus. (A star's magnitude represents its brightness, with lower magnitudes indicating higher levels of brightness.) Within a few weeks, the star had increased in brightness by a full magnitude. As the intruder faded in the following days and weeks, finally disappearing completely from view by October, it was logical to suppose that it was a nova, or an explosion on the surface of a star.

Then, Johannes Holwarda (1618-1651), a Dutch astronomer from Friesland, watched this ruddy star brighten and dim again over an 11-month interval in 1638. While a nova would not be expected to reappear, this object was flashing on and off. Its existence with variable brightness contradicted the Aristotelian dogma that the heavens were both perfect and constant.

Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687) also had become aware of the unusual fluctuations, and in 1662, he honored the star with the name Mira Stella, meaning the "Wonderful Star."

Mira brightens, dims and then brightens again in regular, predictable cycles of approximately 332 days. It always rises to its greatest splendor twice as fast as it fades to obscurity again. At its faintest, Mira is about 15 times dimmer than the faintest star you can see without a telescope. At maximum, it usually reaches third magnitude, or is about 250 times brighter. But once, in 1779, Mira brightened to nearly first magnitude and was almost equal in brightness to the star Aldebaran, reaching a luminosity of 1,100 suns.

Characteristics of the "Wonderful Star"

The reddish Mira, located about 300 light-years from Earth, is an ideal subject for naked-eye study.

It varies in size from 400 to 500 times the diameter of the sun, and yet its mass is no more than twice as great, with a resulting density of about 0.0000002 that of the sun. That's virtually a vacuum by our earthly standards.

Mira typifies a class of stars that number in the thousands and are known as long-period variables, which are also believed to be pulsating red giant stars.

Two for the price of one

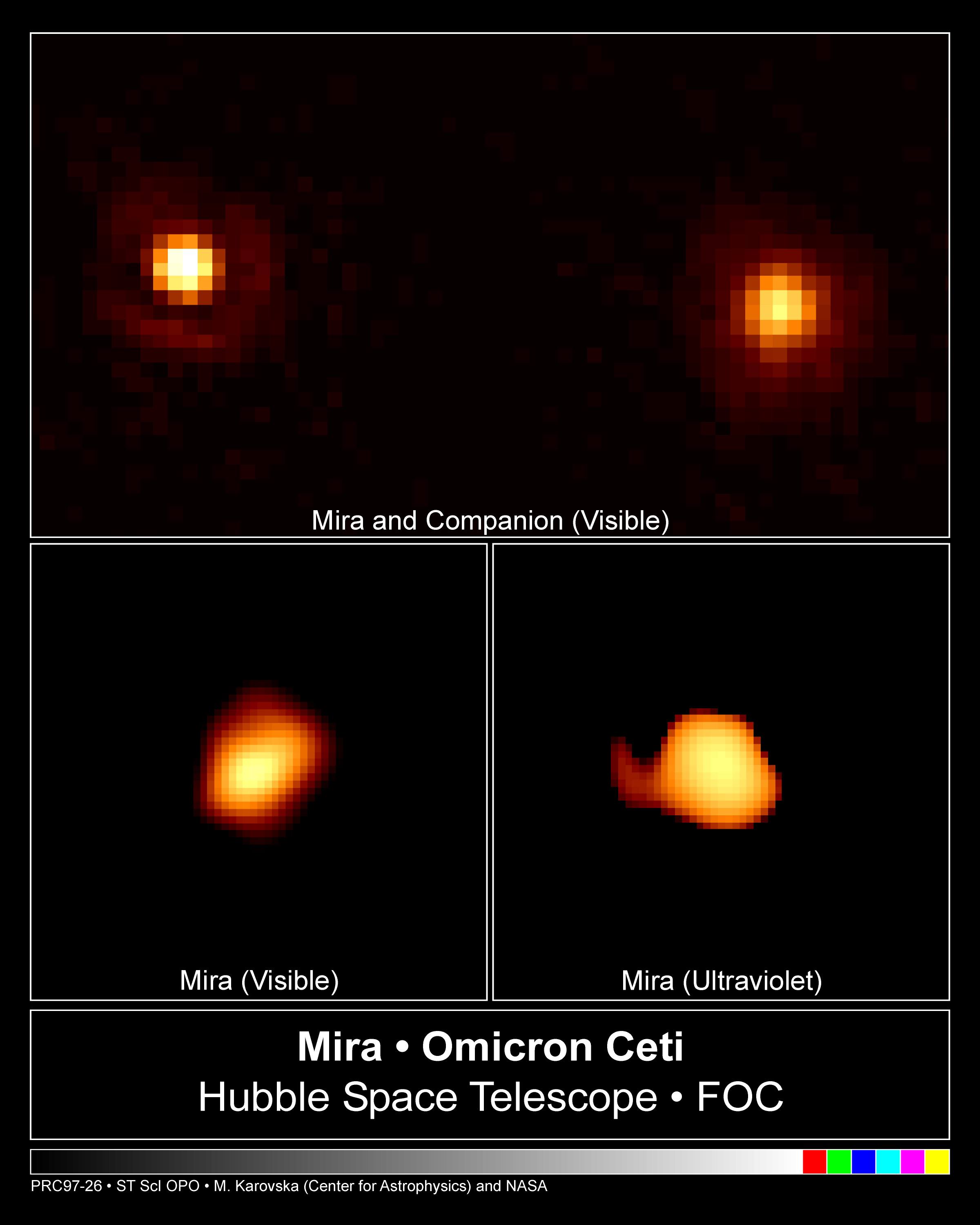

Mira may look like one star, but it is actually two stars. Mira A is the star we see visually, a red giant that expands and contracts with regularity. Mira B — first suspected in 1918 — is a much smaller and dimmer, white dwarf star that was first glimpsed in 1923 at the Lick Observatory in California and was resolved in images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 1997.

In contrast to its much larger supergiant companion, the estimated diameter of Mira B measures less than one-tenth of the diameter yet has a density of 3,300 times that of the sun. In addition, it is gradually accreting mass that it's pulling from Mira A. Such an arrangement is known as a symbiotic system, and in Mira, we have the closest such symbiotic pair to our sun. The two stars are currently separated by about 6.5 billion miles (10.5 billion kilometers).

Stellar surprises

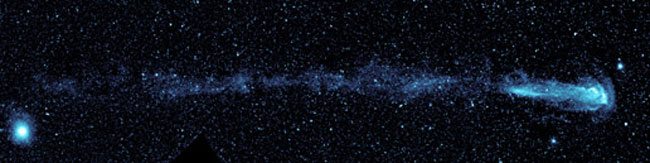

A recent surprising discovery came from NASA's Galaxy Evolution Explorer satellite, which was launched in 2003. It discovered an exceptionally long, comet-like tail of material trailing Mira. The tail — roughly 13 light-years in length — was a surprise, since it is visible only in ultraviolet light.

And right now, this current Mira cycle appears to have been one of the more unusual. On Oct. 22, variable star observer Kerstin Raetz of the Federal German Association for Variable Stars in Germany reported seeing Mira shining at magnitude +2.2 — more than twice as bright as a typical maximum. It has been slowly diminishing in brightness ever since, and this week, it should be at roughly +3.5 magnitude — still bright enough to be readily seen with the unaided eye, though roughly just one-third as bright as it was less than a month earlier; the fading process is now well underway.

- How to See 4 Weird Pulsing Stars in the Autumn Night Sky

- New Stars on the Cosmic Block Are Fast, Bright and Pulsating

- Comet-like Tail Discovered Behind Speeding Star

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.