Monster black hole is a 'cosmic Michael Myers' killing a star and brutally attacking another

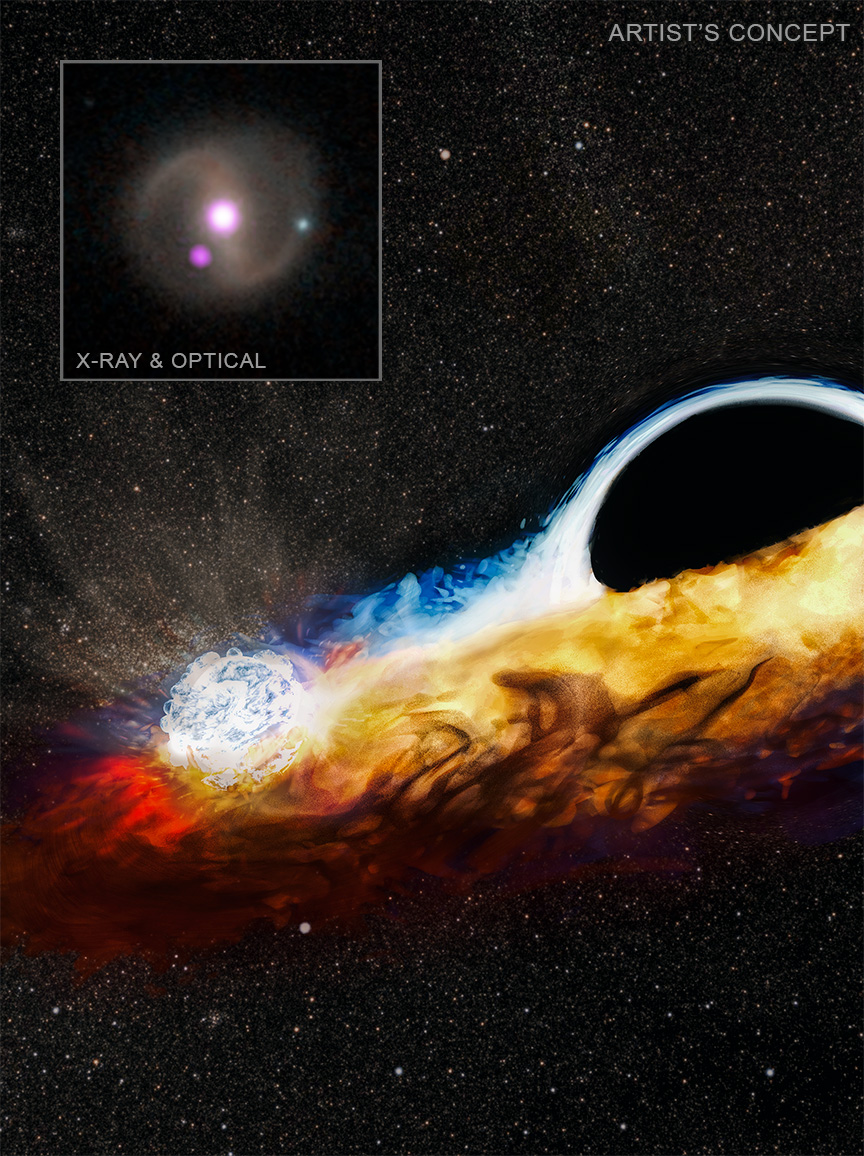

NASA's Chandra X-ray space telescope spotted the supermassive black hole attacking a second star with the remains of a fresh "kill" like the star of the Halloween franchise.

With Halloween approaching, it's the perfect time for a horror film and NASA's Chandra space telescope has spotted a doozy. The X-ray telescope saw a cosmic serial killer remorselessly ripping apart a star and then targeting its next stellar victim.

Like a cosmic Michael Myers, the unstoppable killer of the Halloween horror franchise, the supermassive black hole in a galaxy 210 million light-years from Earth specializes in gory demises. The black hole in the center of AT2019qiz is hurling the remains of the star, which it previously destroyed, at another star or possibly a smaller stellar-mass black hole orbiting it.

This stellar horror movie was first observed by the Zwicky Transient Facility, which saw the violent death of a star due to the gravitational influence of this black hole in a so-called "tidal disruption event" or "TDE" in 2019. Like all the best horror movies, astronomers were eager to catch the sequel, with NASA's Chandra X-ray Space Telescope, the Hubble Space Telescope, the Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER), the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, and other telescopes catching the next installment in 2023.

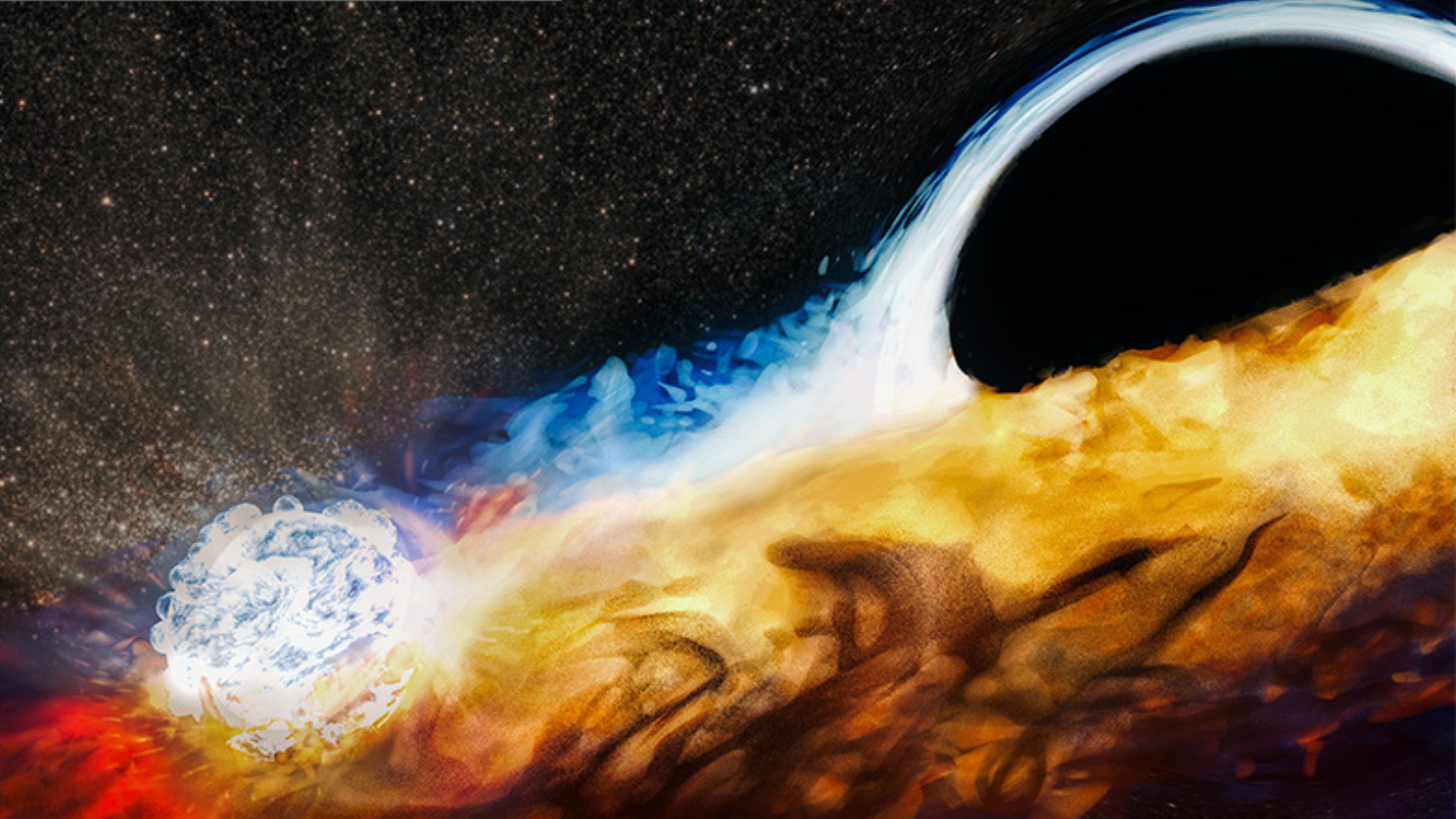

This new installment in this gruesome tale involved the remains of the destroyed star, which have settled around this killer black hole like a graveyard, forming a flattened cloud of stellar material.

This stellar wreckage has extended to the point that an orbiting object repeatedly collides with it as it circles around the supermassive black hole of AT2019qiz. These collisions cause flashes of X-rays seen by Chandra.

Related: Astronomers witness 18 ravenous black holes ripping up and devouring stars

"Imagine a diver repeatedly going into a pool and creating a splash every time she enters the water," team leader Matt Nicholl of Queen’s University Belfast, United Kingdom, said in a statement. "The star in this comparison is like the diver, and the disk is the pool, and each time the star strikes the surface, it creates a huge 'splash' of gas and X-rays. As the star orbits around the black hole, it does this over and over again."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team's research was published on Wednesday (Oct. 9) in the journal Nature and is also available on the paper repository arXiv.

How black holes make stellar spaghetti

TDEs like the one that started this gruesome series of events happen when unfortunate stars venture too close to supermassive black holes. These cosmic titans, found at the heart of all large galaxies, have masses equivalent to millions or billions of suns. And with such tremendous masses come incredible gravitational influences.

When a star gets too close to a supermassive black hole, the gravity is so different at its closest and furthest points from the black hole that powerful tidal forces are generated within the star. This causes that doomed stellar body to be stretched vertically and simultaneously squashed horizontally. This process, colorfully called "spaghettification," turns that star into a long cosmic noodle of plasma.

The black hole can't directly slurp down this stellar pasta because it still has angular momentum. This causes the stellar wreckage to form into a swirling flattened cloud of plasma around the black hole that gradually feeds it, called an "accretion disk."

Astronomers have observed many of these TDEs, which are marked by a single powerful flash of light as the star is ripped apart. Recently, they have also turned up related events that flash in X-rays more than once, repeating multiple times.

These supermassive black hole-centered "quasi-periodic eruptions" had been theorized to be connected to orbiting bodies diving through accretion disks, but this is the first hard evidence of that connection.

"There had been feverish speculation that these phenomena were connected, and now we’ve discovered the proof that they are," team member Dheeraj Pasham of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) said in the statement. "It’s like getting a cosmic two-for-one in terms of solving mysteries."

This evidence came in the form of repeated X-ray bursts from AT2019qiz, which Chandra spotted occurring roughly once every 48 hours. Data from Hubble collected simultaneously allowed scientists to determine the width of the accretion disk around the supermassive black hole, revealing it had spread out enough to allow any object orbiting the black hole for a period of about a week or less to slam through the disk and cause eruptions.

Astronomers can now use these results to search for more quasi-periodic eruptions, which represent killer black holes attacking fresh victims with stellar wreckage.

"This is a big breakthrough in our understanding of the origin of these regular eruptions," Andrew Mummery of Oxford University said in a statement. "We now realize we need to wait a few years for the eruptions to 'turn on' after a star has been torn apart because it takes some time for the disk to spread out far enough to encounter another star."

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.