We've had a shift in weather and another small taste of human stressors at the Haughton-Mars Project (HMP) on Devon Island in the Arctic.

When we arrived here, it was sunny with temperatures in the high 40s and low 50s, and we got used to that. "Look at that scenery!" one of us would say. "How Mars-like!" another would add, and it was. But it was Mars-like in the comfort of a one-Earth-gravity environment, with a breathable atmosphere and ambient temperatures of about 50 degrees Fahrenheit (10 degrees Celsius).

Today we awoke to what might be considered more typically Martian weather. Hard winds all night, and cold. It was about 35 F (1.6 C) with 30 mph (48 km/h) winds; with wind chill, that's well below freezing.

Related: Mars: Everything you need to know about the Red Planet

Rod Pyle is a space historian and author who has created and offered executive leadership and innovation training at NASA's Johnson Space Center. Rod has received endorsements and recognition from the outgoing Deputy Director of NASA, Johnson Space Center's Chief Knowledge Officer for his work.

Mind you, there are plenty of people in Minnesota and other locales more civilized than this who would decry me as a whiner, and I don't disagree, but to this SoCal city slicker, it's frigid here. Add the constant, fine windblown grit coming off the floor of Von Braun Planitia (the broad, silty valley floor that stretches away from the base of the bluff on which the Haughton-Mars Project base is located), and the broadly open terrain that does not impede wind at all, and you have a conspiracy of gritty cold.

All this is a reminder, despite these temporary conditions, of how well adapted to Earth we all are. We are children of this planet; we evolved under the tyranny of one gravity and with the pleasure of 14 pounds per square inch breathable atmosphere. That's the environment for which we were bred. It's unique in the solar system, and so far, from what we've observed, possibly unique in our region of the galaxy. So any discomfort we may be feeling here, while instructive, is absolute child's play compared to the harsh reality of other planets.

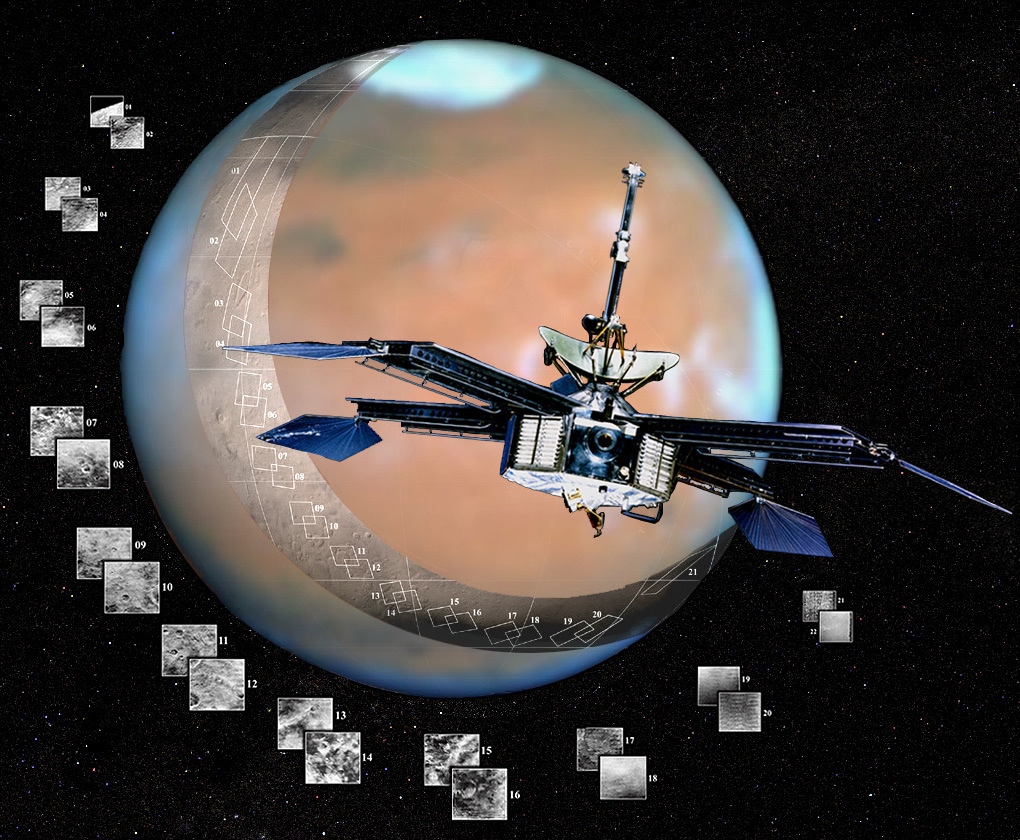

It was not that long ago that the solar system was a kinder, gentler place. I'm old enough to remember a time before Mariner 4 sailed past Mars in 1965; our perception of the other terrestrial planets, while evolving, was still blissfully naive. The notions of astronomers like Percival Lowell had struggled to survive into the second half of the 20th century, but the prevailing idea of Mars as a chillier, bleaker twin for Earth, and Venus as a tropical doppelganger for our planet, died hard. Telescopic and radar observations were chipping away at the "sister planets" idea, but science fiction authors and filmmakers could still push the notion, without too much stress, that we would one day be walking around Mars in polar garb with an oxygen bottle to augment our breathing — "Not much different than climbing Mount Everest," as some armchair scientists opined.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Oh, how wrong we were.

When Mariner 4 sped past Mars on July 15, 1965, the Martian empire of Ray Bradbury's fever dreams was finally smashed to red dust. By the time the data were evaluated, Mars was revealed to have an atmosphere about 1/100 the density of Earth's, and it was so CO2 rich as to be unbreathable in any case. By the time subsequent Mariners has reconnoitered the Red Planet, and the twin Viking landers had completed their first months of service at Chryse Planitia and Utopia Planitia, we began to understand that the surface was bathed in killing radiation and that the soil was likely laced with deadly peroxides. The romantic notion that we had a nearby, near-twin world that could provide us a second home receded into interplanetary distance.

Cut to 2022. We've now had well over a dozen missions to Mars, currently have our sixth rover exploring the surface (including China's Zhurong), and receive continuous reports of surface weather and conditions surrounding the planet. We know how hostile Mars is to human life (and don't even get me started on Venus!), and what it would take to survive there.

While places like the Haughton-Mars Project do not perfectly model the soil chemistry, intense radiation, lower gravity, or thin atmosphere of Mars, there is still great value in the work done here. The geology of the region strongly resembles that of Mars, as does the terrain that hosts it.

According to Mars Institute planetary scientist and HMP creator Pascal Lee, these may point to a cold and icy climate history for Mars — a notion somewhat at odds with current thinking. Methods of traversing the Martian surface, using spacesuits and robots, collecting samples, doing basic analyses on site, and other experiments are conducted. Increasingly, aerial exploration methods such as NASA's Ingenuity helicopter are being evaluated with promising results. The more you can learn on Earth, the less you will have to learn on Mars, which will save effort, money, and possibly lives.

As Michael Hecht, the Principal Investigator on the MOXIE ISRU experiment that is aboard the Perseverance Mars rover once said to me, "Many technology demonstrations are doomed to succeed on Earth," and by extension to fail in space. Testing everything that can be tested on Earth, in a place like Devon Island, will smooth the journey when it comes.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rod Pyle is an author, journalist, television producer and editor in chief of Ad Astra magazine for the National Space Society. He has written 18 books on space history, exploration and development, including "Space 2.0," "First on the Moon" and "Innovation the NASA Way." He has written for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech, WIRED, Popular Science, Space.com, Live Science, the World Economic Forum and the Library of Congress. Rod co-authored the "Apollo Leadership Experience" for NASA's Johnson Space Center and has produced, directed and written for The History Channel, Discovery Networks and Disney.