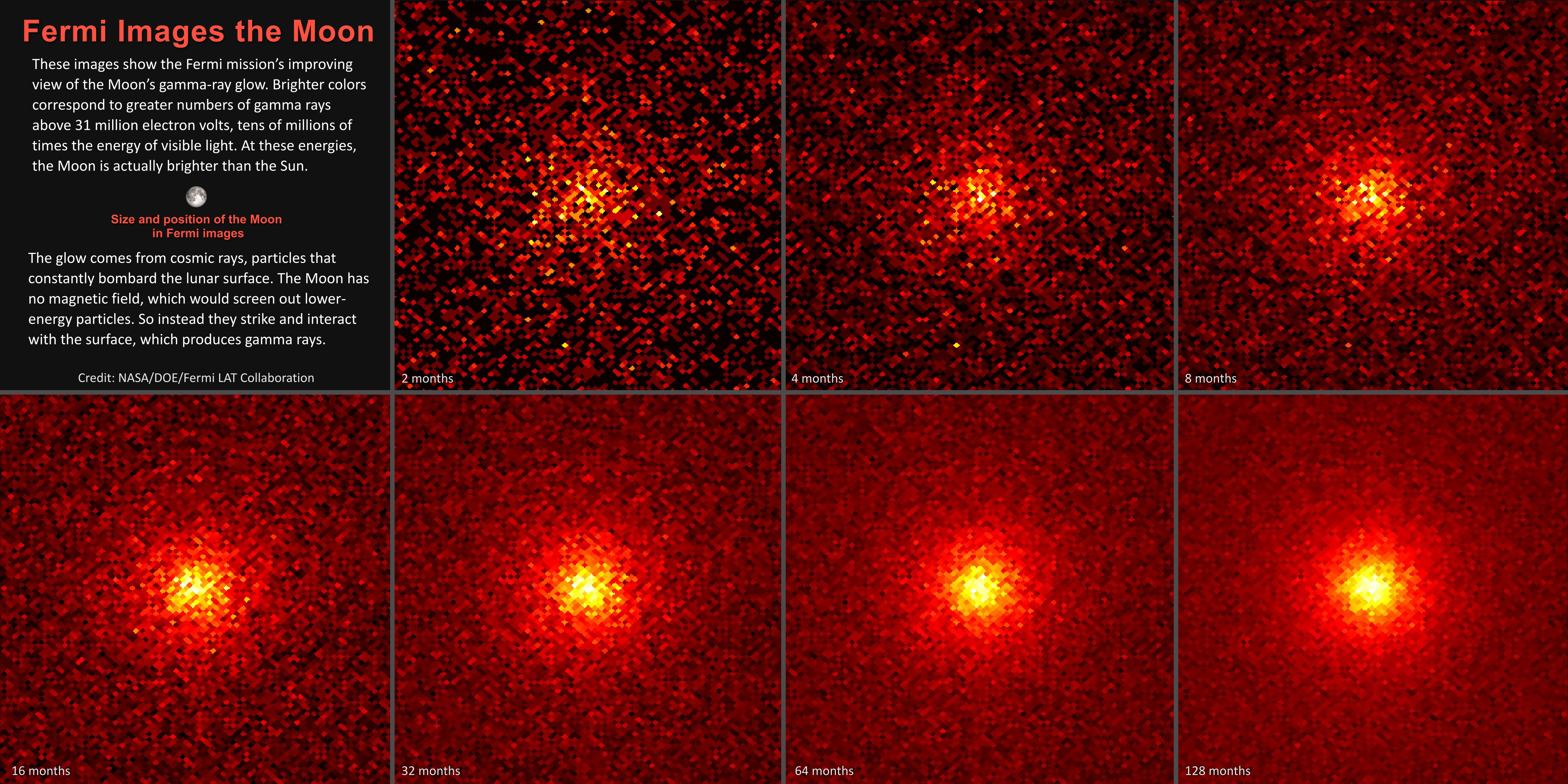

The Moon Is Brighter Than the Sun in These NASA Gamma-Ray Telescope Views

The sun is the brightest object in our skies — but it wouldn't be if we could see incredibly energetic gamma-rays as well as visible light.

That's precisely the light that NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope is tailored to see. The instrument launched in 2008 to help astrophysicists understand objects like supermassive black holes, pulsars and cosmic rays.

Cosmic rays are responsible for the moon's eerie glow in the instrument's sight. "Cosmic rays are mostly protons accelerated by some of the most energetic phenomena in the universe, like the blast waves of exploding stars and jets produced when matter falls into black holes," Mario Nicola Mazziotta, a researcher at the National Institute for Nuclear Physics in Italy who works with the Fermi data, said in a NASA statement.

Related: Gamma-Ray Universe: Photos by NASA's Fermi Space Telescope

Unlike Earth, the moon isn't cocooned in a protective magnetic field that deflects most cosmic rays. A steady stream of these energetic particles slams into the moon's surface and creates gamma-rays, a few of which bounce off the satellite.

That hail would be a serious problem for lunar explorers. Figuring out how to protect humans from cosmic rays is one of the tasks that NASA needs to tackle as a part of its Artemis program, which aims to land astronauts on the moon by 2024.

But without humans in the equation, all those collisions have a bright side: The gamma-rays they produce mean that, when Fermi tunes in to a specific class of light, the moon appears to be brighter than the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Just how much gamma radiation is involved varies over the course of an 11-year solar cycle. But because the cosmic rays aren't streaming off the sun, as visible light is, there's no distinction between a full moon and a new moon in gamma-ray vision.

"Seen at these energies, the moon would never go through its monthly cycle of phases and would always look full," Francesco Loparco, also a researcher at the National Institute for Nuclear Physics who works on the project, said in the same statement.

- NASA Spacecraft Lifts Veil on Universe's Brightest Explosions

- Amazing Moon Photos from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

- 100-Year Cosmic Ray Mystery Solved with Supernovas (Photos)

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.