Computer-simulated moon dust may help lunar robots pass a major hurdle

Scientists have developed a new computer model that simulates how moon dust behaves in lunar gravity. They hope it will help future robotic moon explorers to do their job more safely.

Scientists have developed a new computer model that simulates how moon dust behaves in lunar gravity. They hope it will help future robotic moon explorers to do their job more safely.

Moon dust, or regolith, is a pesky material. It's superfine, yet sharp like glass. When stirred, it floats suspended in the moon's low gravity environment seemingly forever. During the Apollo-era missions, it famously even got "“everywhere" — tearing up spacesuits, blocking sensors and clogging mechanical components, according to NASA.

In the future, robots on the moon will have to do more in this irritating moon soil than just land and roam around. Scientists will likely ask these machines to build space stations, extract water and perhaps 3D-print tools someday, too. And a new computer model, developed by researchers from the University of Bristol in the U.K., will allow engineers to practice with these lunar robots in simulated moon dust before actually sending them to the moon for real.

Related: Intuitive Machines' Odysseus moon lander beams home 1st photos from lunar surface

"Think of it like a realistic video game set on the moon," Joe Louca, a researcher at the School of Engineering Mathematics and Technology at the University of Bristol and lead author of the paper, said in a statement. "We want to make sure the virtual version of moon dust behaves just like the actual thing, so that if we are using it to control a robot on the moon, then it will behave as we expect."

Other computer models of moon dust have been created before, but those were either too complex and therefore too difficult to run in real time, or not realistic enough. The Bristol team's goal was to create something in between, a mechanism that could create useful simulations while not requiring that much computational power to run.

"Our primary focus throughout this project was on enhancing the user experience for operators of these systems — how could we make their job easier?" Louca said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

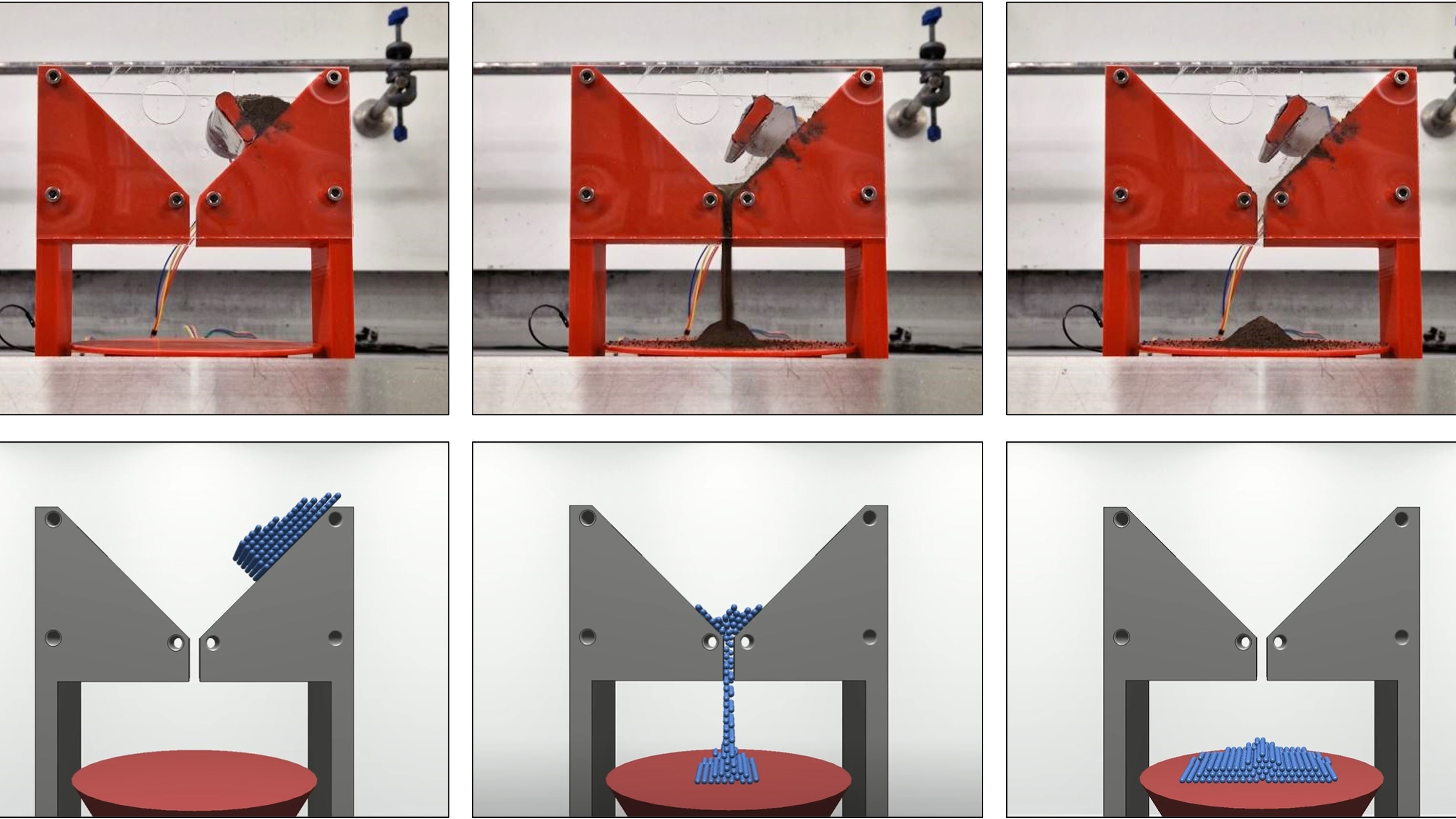

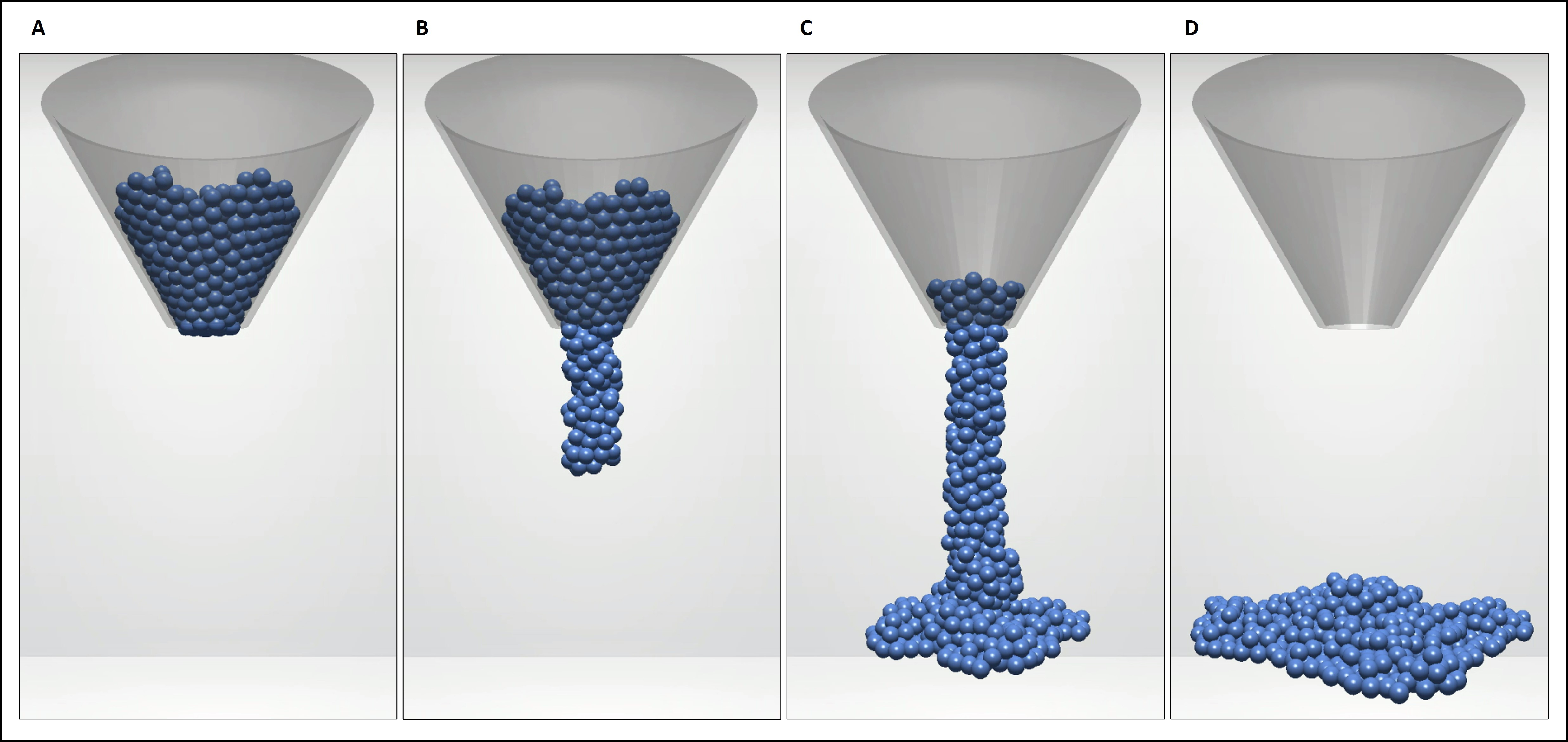

The crew used an earlier, simpler model developed by their colleagues in Germany, which could mimic the density, stickiness and friction of lunar dust as well as recreate the eerie conditions of lunar gravity, which is six times weaker than Earth's. That model, however, could only recreate small amounts of lunar dust, which wasn't sufficient to simulate actual rover operations. The researchers then compared their model with a physical one, using artificial regolith similar in composition to lunar dust.

"We conducted a series of experiments — half in a simulated environment, half in the real world — to measure whether the virtual moon dust behaved the same as its real-world counterpart," said Louca.

The project was completed in cooperation with European aerospace manufacturer Thales Alenia Space, which is developing several moon exploration technologies including a payload that could extract oxygen from lunar soil.

The study was published in the journal Frontiers in Space Technologies on Feb. 22.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.

-

Cdr. Shepard Should those robots even be sent to the moon at all? Why bother with lunar exploration when there's an outside chance it could trigger a climate cataclysm on Earth?Reply

And how about the carbon footprint of the companies contracted to manufacture these robots?

We're living through a climate crisis, Ms. Pultarova. I'd behoove you and yours to not treat the apocalypse so lightly. -

Unclear Engineer So how did they simulate the 1/6th gravity of the Moon? And how did they simulate the electrostatic charge behavior is a vacuum? Making a computer model that you think is realistic is probably easier than creating a physical model to test it here on Earth. So, other than going to the Moon to verify and/or tune the dust behavior model, how are they confident that it is realistic enough?Reply