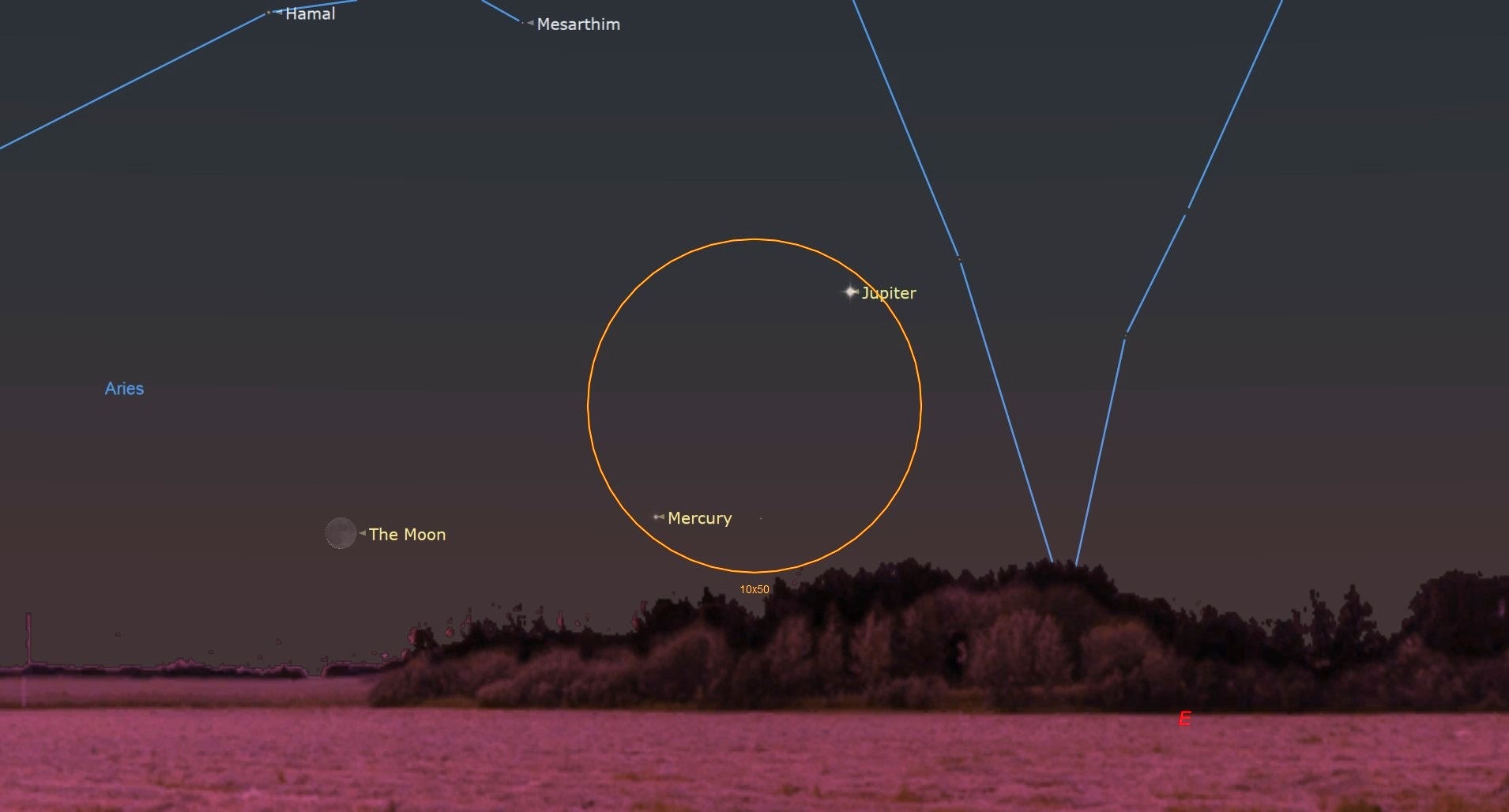

See the moon meet up with elusive Mercury in a conjunction today

Both the moon and Mercury will be in the Aires constellation during the conjunction.

The moon will meet up with Mercury, the solar system's smallest planet and the closest to the sun, in the sky today.

The 28-day-old moon will pass to the north of the tiny planet, with the two coming to within around 3°35' degrees of each other. Both the moon and Mercury will be in the constellation of Aries during the conjunction. The two celestial objects will share a right ascension, the celestial equivalent of longitude, in an arrangement astronomers call a conjunction.

Skywatchers in New York City will be able to see the moon and Mercury shortly after they rise at 4:54 a.m. EDT (0854 GMT) until just before they drop just below the horizon at around 6:14 p.m. EDT (2214 GMT), according to In the Sky.

The conjunction will occur during daylight hours with the sun above the horizon. Observing celestial events such as this conjunction is possible during the day, but comes with risks. Skywatchers interested in observing this event should take precautions not to look directly at the sun or to direct binoculars or telescopes in its general direction.

Related: Night sky, May 2023: What you can see tonight [maps]

Want to get a good look at the moon or Mercury? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

During the conjunction, the moon, which will be only 5% illuminated as it heads to the next completely dark new moon and the start of a new 29.5-day lunar cycle on Friday (May 19). The moon will have a magnitude of around -8.8 during the conjunction, with the minus prefix indicating a bright object over Earth. Mercury will have a magnitude of 1.6 during the celestial arrangement, making it somewhat more difficult to observe.

Both bodies will have a right ascension of 02h18m20s, while the moon will have a declination of +14°09'. Mercury will have a declination of +10°33'.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Thanks to its proximity to Earth, the moon is much larger than Mercury in the sky over our planet, having an angular size of 31'20"2 compared to Mercury's angular size of 10"3.

The difference between the size of the moon and the size of Mercury in the solar system isn't actually that great. The moon has a diameter of 2,158 miles (3,474 kilometers), while Mercury is just 3,031 miles (4,879 kilometers) wide. This means the tiny planet is only 1.4 times the size of our moon.

Mercury is, however, around 4.6 times more massive than the moon, thanks to its composition of 70% metal and 30% silicate, which gives the planet an impressive density of around 5.4 grams per cubic centimeter. This makes it the solar system's second densest planet after Earth, which has a density of 5.4 grams per cubic centimeter. The moon is lighter, with a density of just 3.34 grams per cubic centimeter.

Despite coming close together in the sky, the moon and Mercury will still be too widely separated in the sky on Wednesday to be seen in the field of view of a telescope. The two will be visible together within the wider field of view of binoculars, however.

If you are hoping to catch a look at the moon and Mercury during the conjunction, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

And if you want to try your hand at taking your own pictures of the night sky, check out our guides on how to photograph the moon, as well as the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor's Note: If you snap an image of the conjunction between the moon and Mercury, and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.