Surviving the lunar night can be a challenge for astronauts on the moon

The moon's lunar day/night cycle means fourteen days of continuous sunlight followed by fourteen days of constant darkness.

As multiple nations plot out their moon exploration strategies, how best to survive the lunar night gives space engineers the cold sweats.

The moon's lunar day/night cycle at most locations on the surface includes fourteen Earth days of continuous sunlight followed by fourteen days of constant darkness and intense cold.

Due to the lack of a moderating atmosphere, temperatures on the lunar surface can range from 248 degrees Fahrenheit (120 Celsius) during the day to minus 292 F (minus 180 C) during the night. Permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) on the moon can be even colder, plunging down to minus 400 F (minus 240 C).

Related: Artemis 1: The first step in returning astronauts to the moon

Pluses and minuses

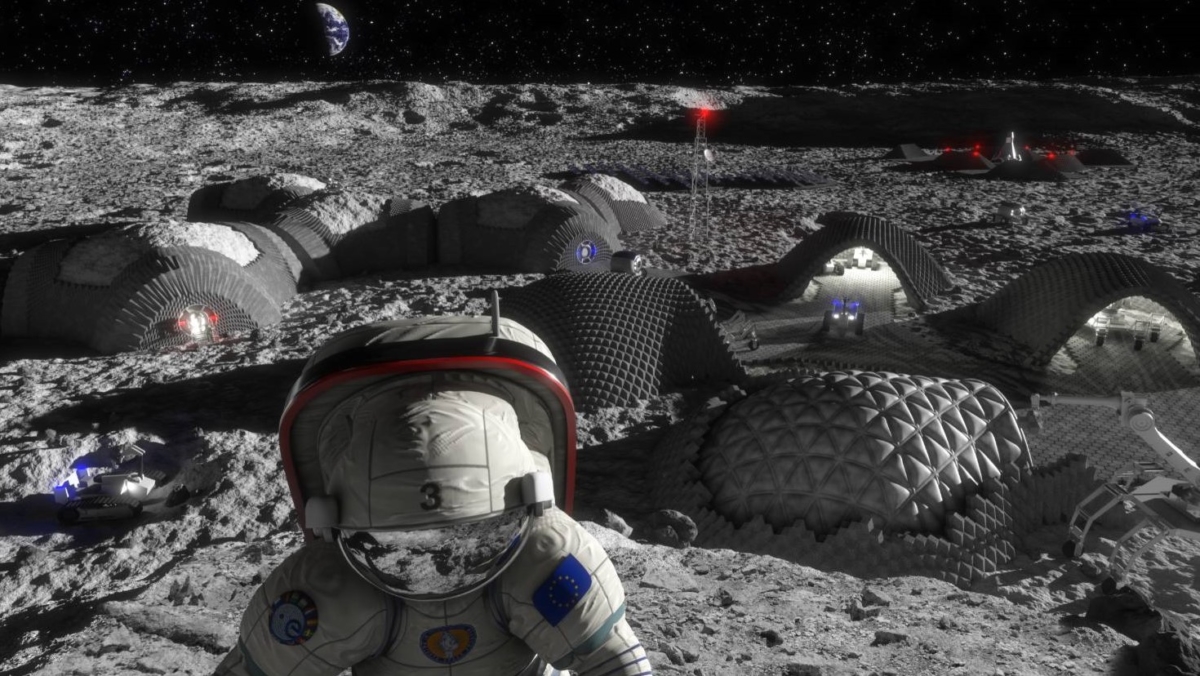

All those pluses and minuses add up to one of the most demanding environmental challenges that future moon expeditions will face. Attaining and gaining longer and longer human stays — perhaps gaining permanent status — will mean coming to grips with the moon's vicious environment.

In fact, craters within permanently shadowed regions are sun-shy spots on the moon in which quantities of water ice could reside. Those deposits would be ideal for processing into oxygen, water, even rocket fuel.

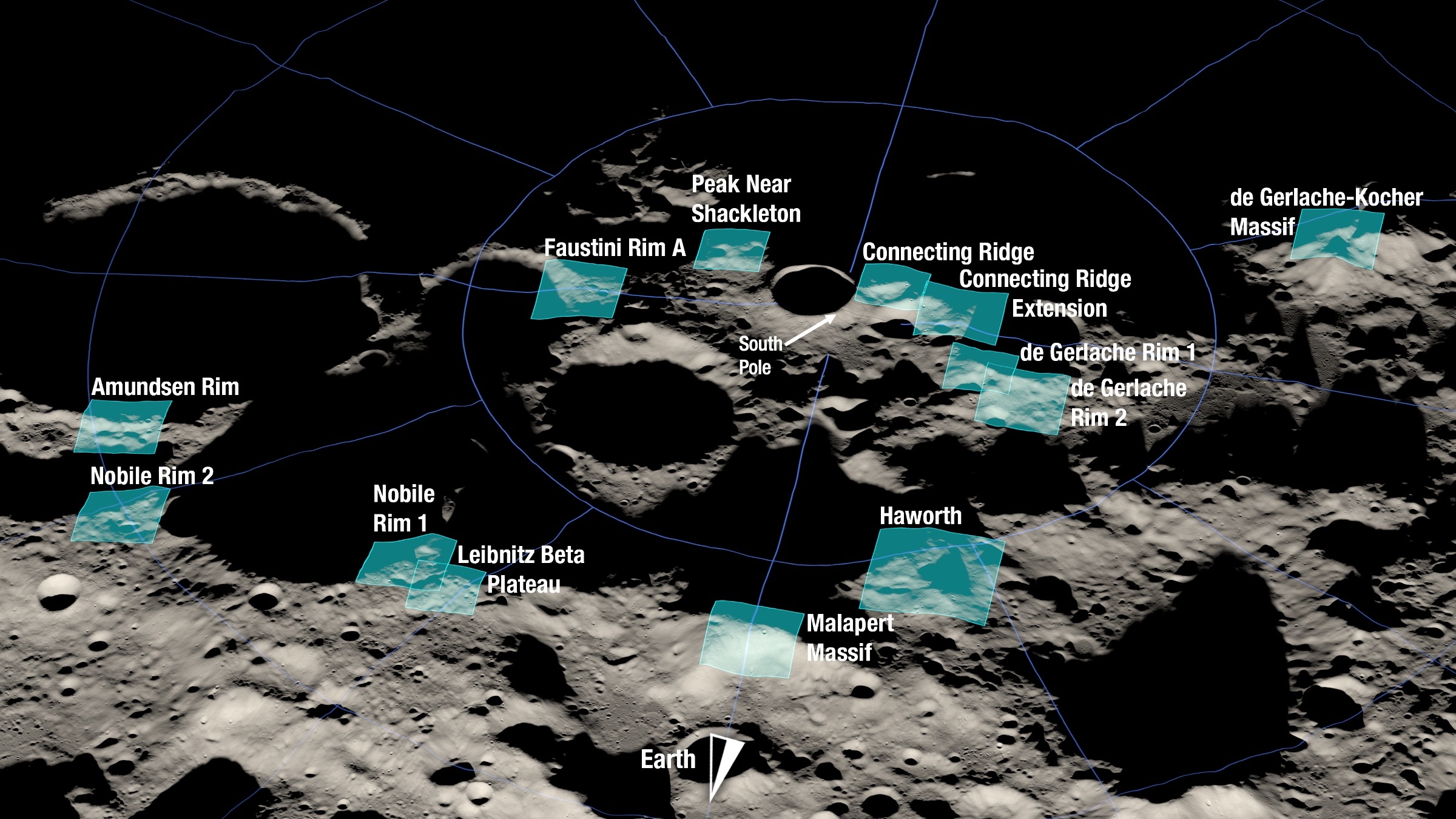

Moon exploration planners are laying out what has to happen to operate successfully on the moon, particularly at the lunar south pole, loaded with PSRs and conceivably a rich haven for harvesting water ice.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But here is the cold, chilly fact: it isn't easy.

Read more: The moon's strange warm pits may be the most pleasant place for astronauts

Basic problem, two branches

Dean Eppler, chief lunar scientist at The Aerospace Corporation, said surviving the night on the moon is not only a key issue for a lunar south pole site, but for any place we want to be on the moon for longer than lunar daytime.

"I think the basic problem has two branches," Eppler told Space.com. "Simple survival during the lunar night, and operations during night time, regardless of whether it's a 'normal' day night cycle like you would get at anywhere other than the poles, and the variable darkness you get at the poles due to the very low solar inclination angle."

Eppler said that, for future missions, particularly for landed missions off the polar latitudes, hunkering down may still be the best decision for science operations.

"You don't do field geology at night," Eppler said, "but that will probably be the time to do 'inside' activities, such as life sciences, sample analysis and culling, engineering/maintenance work." Those are tasks mostly not carried out during the day when crew members are engaged in maximizing their surface, moonwalking operations, he said.

Eppler said he's optimistic in taking on the lunar night. "I think we are much better equipped to handle that now than we were during any other time we've considered lunar exploration."

Profoundly cold

Although surviving the lunar night outside the polar regions is still an issue, "I think we have that pretty well in hand, and that also goes for areas of the poles shadowed by the existing terrain as the Sun travels around in the sky."

However, when it comes to the poles, Eppler sees a much more complicated problem. Firstly, there will be significant areas that get shadowed by the terrain long enough that it's going to get very cold in those locations — not PSR-cold, but still not unlike the equatorial night.

"Secondly, we'll have to deal with the problems of working in any either PSR area, or areas that, while not in permanent shadow, are still shadowed much of the time, long enough to be profoundly cold inside of them," said Eppler. "This is a huge challenge … so much so that I think we'll need, for instance, a special set of tools that we only use in cold conditions," he added.

Keep-alive warmth

Coping with the ultra-cold shouldn't be a hard problem to solve, said Philip Metzger, a planetary scientist with the Florida Space Institute at the University of Central Florida.

"With even just a little energy and good insulation the vehicle can stay warm. The New Horizons spacecraft kept its electronics at room temperature even when it was far from the sun at Pluto," Metzger told Space.com.

The key issue is, where can we get the energy on the moon?

Radioactive decay sources can be used, for one example. Radioactive Heater Units (RHUs) can be placed on the vehicle at appropriate points, Metzger said. "Without a radioactive source it becomes more challenging, though."

Metzger envisions a stand-alone asset that has adequate battery capacity to provide the "keep-alive-warmth" during the night. "A rover could plug in through the night. After sunrise the asset will recharge. That would take some mass on the moon for adequate storage, but with the new lunar landers, including the SpaceX Starship coming online, it should be easily doable," he said.

Good set of assumptions

Present-day data sets are yielding key temperature data on the moon, advised Noah Petro from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. He is project scientist for the NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) mission now circling the moon.

"Fortunately the temperature data we have from the Diviner instrument on LRO has given us a fantastic set of bounding conditions for what to expect thermally at the poles. From this dataset we know the expected cold temperatures at night and warmth during the day," said Petro.

As far as the engineering capacity to ring out hardware, Petro said given that researchers have a good set of assumptions for the environment (temperature, radiation, etc), he foresees that the issue of lunar survival can draw upon an already mature understanding of the engineering requirements to operate through lunar nights.

Message from Apollo

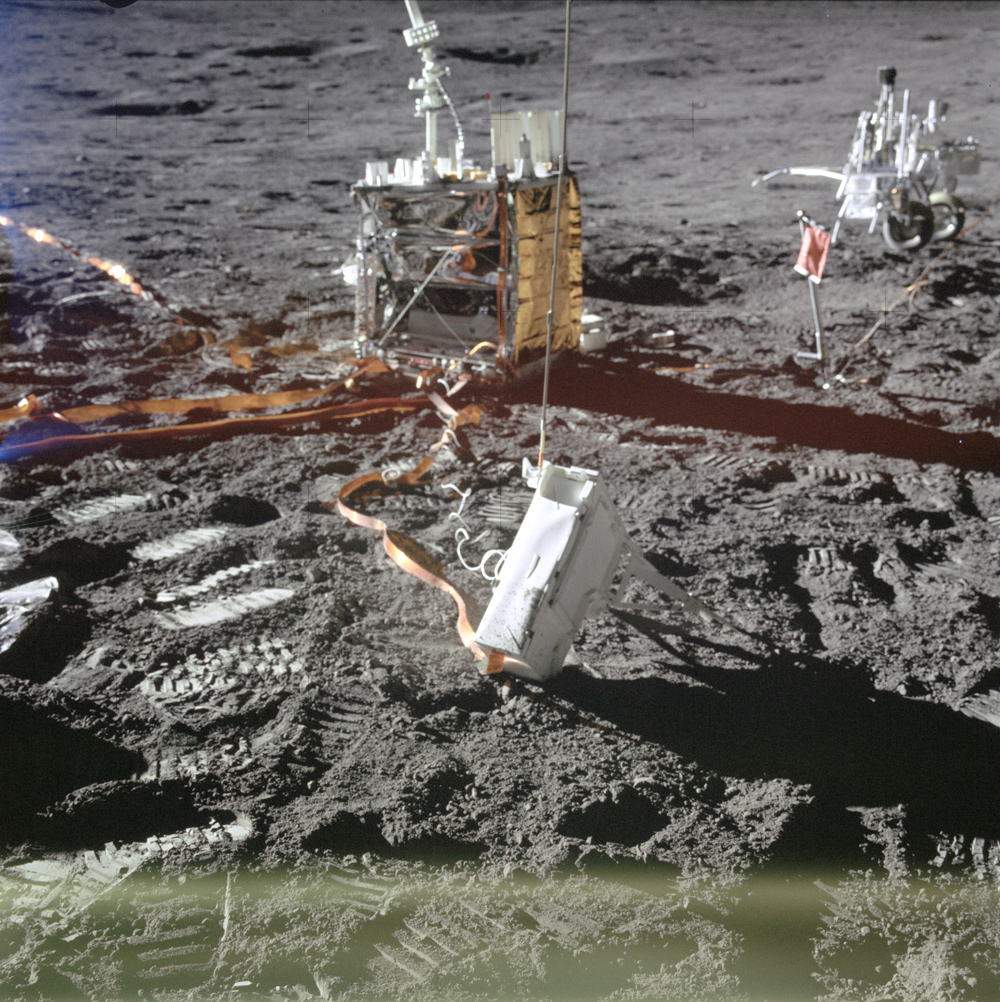

Looking back on the 20th century Apollo era, there are lessons to be re-learned, said Clive Neal, a lunar exploration expert in the department of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

Neal points out that the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) consisted of scientific instruments set up by moonwalkers at the landing site of each of the five moon-landing Apollo missions to land on the Moon following Apollo 11; Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin left a smaller set of devices called the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package.

However, Neal said the issue is if solar is the way to do this? Is battery technology good enough to allow operations during the lunar night?

"For many things, just surviving the night, is not good enough," Neal added. "We need to be able to match what was done 50 years ago, in my humble opinion!"

Moonwalking suits

What's it going to be like strolling across and working upon the lunar territory, Artemis style?

Regarding moonwalking suit systems, including boots, gloves and the backpack-like portable life support system, the thermal design issues will be severe, Eppler of The Aerospace Corporation said.

"For instance, say you're standing ankle deep in a very cold, shadowed area, but your legs, torso, etc., are in direct sunlight. You'll need to ensure that the boots and pressure garment material don't freeze and break, while ensuring that the upper parts of the suit system don't become so hot that serious heat stress to the crewmember is a significant issue," Eppler said. "It's real problem."

The good news, Eppler concludes, is that Artemis technologists are trying to come to terms with the whole survive the night state of affairs.

"That says to me that we will find solutions at some point," Eppler said. "The point where you get into trouble is when folks don't understand or accept the magnitude of the problem … but I don't think that is the case here," he concluded.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.