It would seem in our 21st century world, that most everything needs to be branded. That is exactly the case this month regarding the moon, especially since this is a "double full moon month."

The full moon of Oct. 1 acquired the title of "Harvest Moon" because it was the full moon occurring nearest in the calendar to the autumnal equinox. Usually the September full moon gets that title, but this year it came much too early (on Sept. 2). There are other versions of this rule that the Harvest Moon is the full moon that comes either at or after the equinox, which would also put it in October more often than not.

The occurrence of the autumnal equinox can vary from year to year, falling either on Sept. 22 or Sept. 23. A full moon generally occurs 14.7 days after new phase of the moon. So, the earliest possible date in the calendar that a Harvest Moon can occur would be Sept. 7; the latest possible date is Oct. 7. This year will be the last October Harvest Moon until 2028 (when it will occur on Oct. 3).

Related: Full moon names (and more) for 2020

It is often said that farmers utilize the full moon's light at this time of the year — the climax of the harvest — by working late into the night by the light of the moon. And for several nights in a row, centered on the date of full moon, instead of rising its average of 50 minutes later each night, it rises only about 24 minutes later.

But in truth, the name "Harvest Moon" has little literal meaning today. It reaches back to a time when the farmer was pressed by the season and welcomed a moonlit week to stretch his rapidly shortening days out in his field that must be harvested before the deep frosts and short days and long cold nights of the impending winter. There were numerous chores for the farm family to complete and the Harvest Moon was a welcome lantern in the evening sky.

The unseen proxigean moon

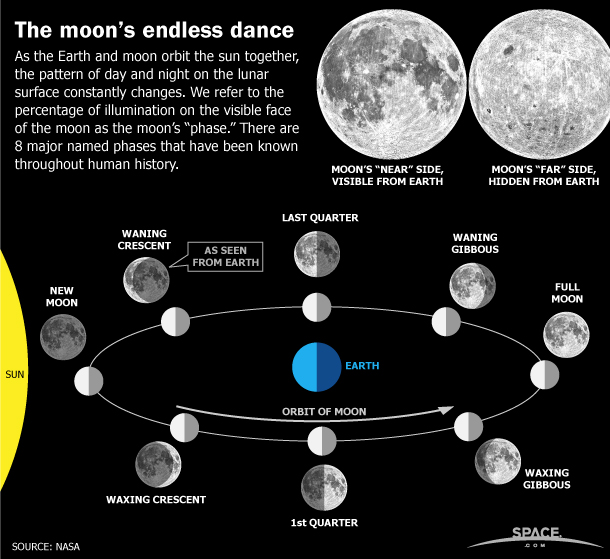

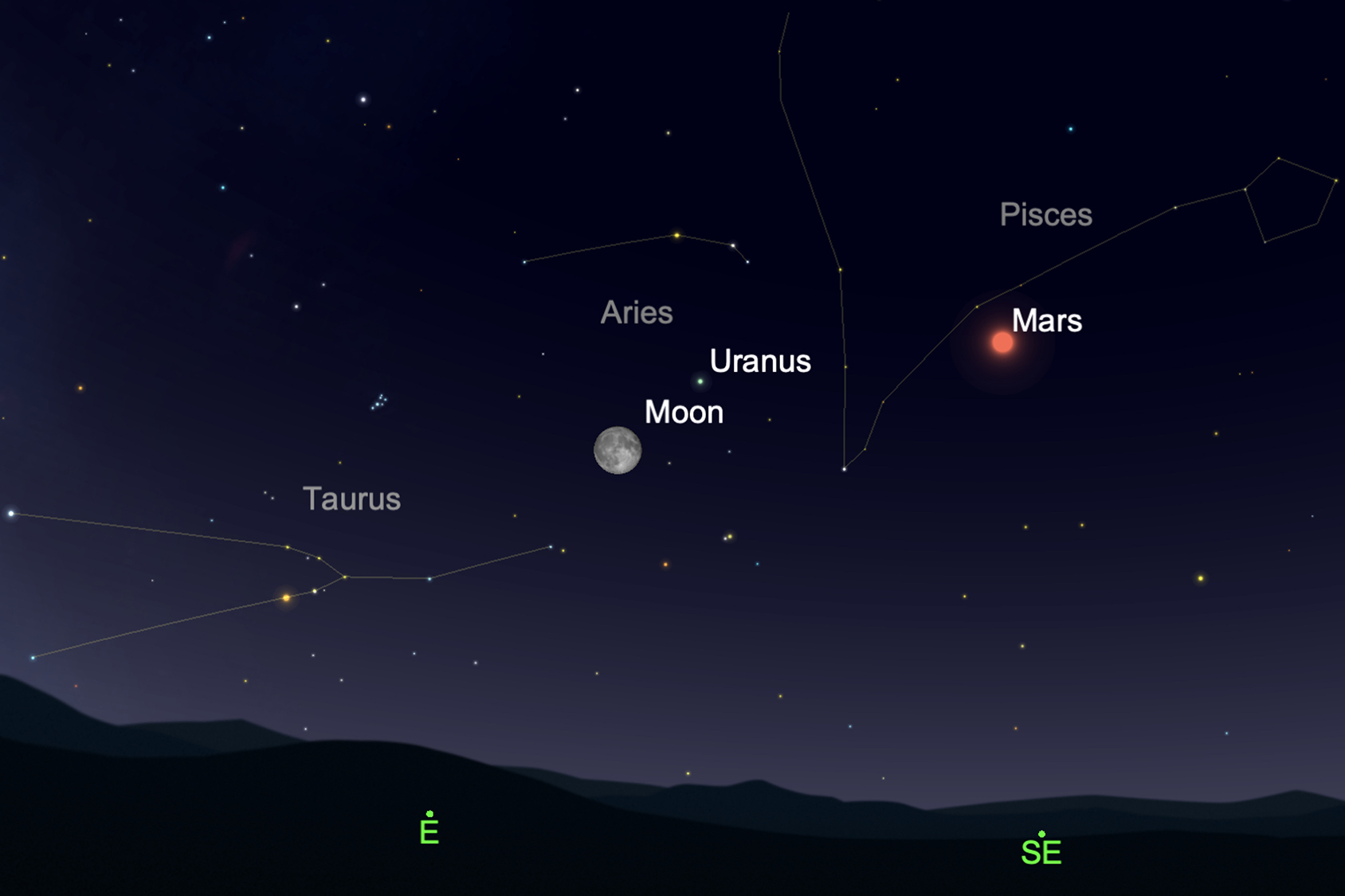

Now the moon is on the wane, gradually diminishing in illumination in the predawn skies as a progressively thinning crescent. By Thursday morning (Oct. 15), look for it hovering just above the eastern horizon an hour before sunup. By then it will have shrunk to a razor-thin arc of light, less than 3% illuminated.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The next day (Oct. 16) is the new moon, at 3:31 p.m. EDT (1931 GMT). But this particular new moon will come within less than 4.5 hours of perigee, or the point in its orbit at which the moon is closest to Earth. In fact, the moon's distance on this day is 221,775 miles (356,912 kilometers), which is only 3 miles (5 km) farther away than the full perigee moon of April 7 — the so-called "supermoon."

Some might even prefer to brand this unseen moon as a "proxigean moon," because both the sun and the moon will be on the same side of Earth.

Every month, "spring tides" occur when the moon is both new and full. At such times, the moon and the sun form a line with the Earth, so their tidal effects add together. (The sun exerts a little less than half the tidal force of the moon). "Neap tides," on the other hand, occur when the moon is at first and last quarter and works at cross-purposes with the sun. At these times the tides are weak.

Related: 2020 Moon Phases Calendar

Tidal force varies as the inverse cube of an object's distance. This month the moon is 14% closer at perigee than at apogee. Therefore, it exerts 48% more tidal force during the spring tides of Oct. 16 than during the spring tides near apogee with the full moon at the end of the month.

Yet, although the upcoming new moon's tidal effects on Earth will be just as potent as the much-ballyhooed "supermoon" of last April, it likely will get little or no notice by the mainstream media simply because we can't see it.

Bishop George Berkley (1685-1753) once asked the question: "If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound?" To which I would ask: "If the moon comes unusually close to Earth and no one sees it, will it have a significant effect on the tides?"

The answer: Yes, it will.

This upcoming new moon, coinciding with practically the closest approach to Earth in 2020, will indeed cause an unusually large range of tides, which could be especially problematic if a hurricane or tropical storm threatens the Gulf of Mexico or the Atlantic Seaboard. If that be the case, then most assuredly — in spite of its invisibility — the mainstream media will make you aware of this month's new moon.

What a way to end the month!

Finally, we'll have a second full moon to enjoy on Oct. 31. Popular culture regards the second full moon occurring in a month as a "Blue Moon."

And traditionally — in Algonquin Indian lore — the full moon that comes after the Harvest Moon is known as the Hunters' Moon, when hunters tracked and killed their prey by autumn moonlight, stockpiling food for the coming winter.

Commenting on Hunter's Moon lore in their Oct. 26, 1969 edition, The New York Times noted: "The Hunter's Moon is and always was a summons to man and his dog. Back in the hills, even now, the raccoons are on notice: The man is ready to hunt in the October moonlight. The hounds eager to run."

But in addition, this particular full moon comes within less than a day of apogee — its farthest point from Earth — 252,522 miles (406,394 km) away. So, this full moon is nearly 14% smaller than in April, the antithesis of a "super" moon, or as the mainstream media calls it, a "micromoon" or "minimoon."

And this all happens on Halloween. And with the exception of Christmas, what holiday goes hand-in-hand with a full moon more than Halloween?

So, get ready to finish out October with a Micro Halloween Blue Hunter's Moon.

What a mouthful of monikers!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.