Mysterious magnetism in Apollo moon rocks is natural in origin, new study finds

The findings disprove one of two major oppositions to the theory that the moon powered its own magnetic field.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Back in the 1980s, geophysicists analyzing moon rocks brought to Earth during Apollo missions were surprised to find very strong magnetic fields etched onto those samples. The moon is not large enough to power such a field, let alone do so for more than 1.5 billion years. How then, did these lunar samples get magnetized?

The conundrum had previously led a few researchers to suspect other sources of magnetism, including the possibility that the Apollo spacecraft ferrying the samples back home may be responsible. But now, a new study demonstrates that the magnetization preserved in lunar rocks is, in fact, natural in origin — and that spaceflight does not have a significant impact on the force. These findings disprove one of two big oppositions to the theory that the moon powered its own dynamo.

Magnetized rocks can shed light on the history of planetary magnetic fields, which are crucial to protect atmospheres. Knowing such samples are not tarnished by spacecraft is therefore important for future sample return mission planning. NASA has an ambitious endeavor to collect rock and dust samples from Mars, for instance, which will be brought back to Earth for analysis.

"You want to know that the spacecraft returning your sample is not magnetically frying your rock, essentially," Sonia Tikoo, an assistant professor of geophysics at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability and the lead author of the new study, said in a statement.

Related: How helicopters on Mars could find hidden magnetism in planet's crust

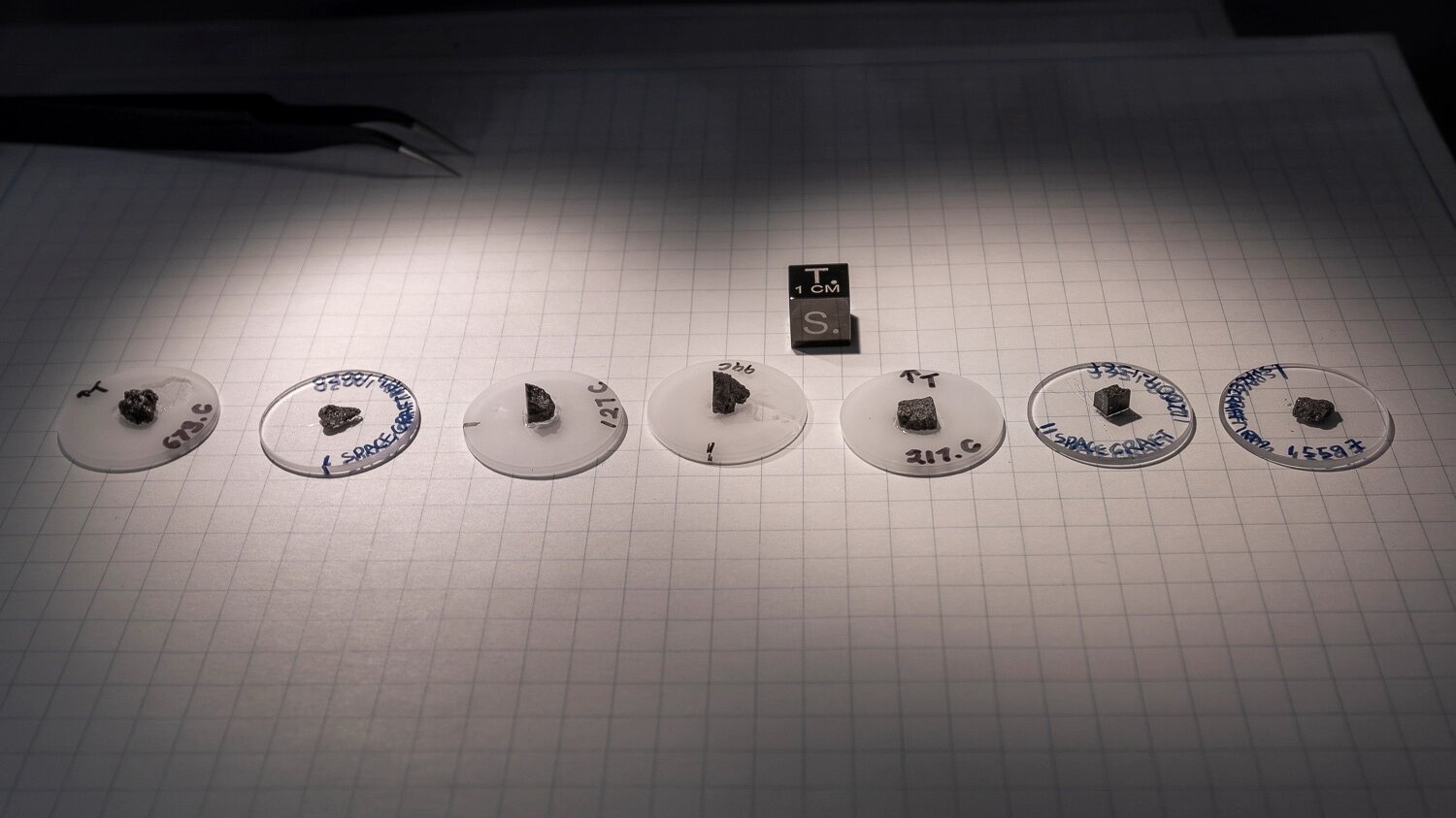

To arrive at their conclusions, Tikoo and study co-author Ji-In Jung exposed eight moon rock samples from four Apollo missions to magnets that generated magnetic fields with strengths equivalent to those generated onboard a spacecraft. For two days — which replicated a return journey from the moon — the samples were specifically exposed to a field strength of 5 millitesla, which is roughly 100 times stronger than Earth's magnetic field, according to the new study.

Later, the team observed how the "magnetic contamination" decayed and found it could be easily cleaned using standard methods.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This study proves that we can do extraterrestrial paleomagnetism with mission-returned samples," Tikoo said in the same statement. "I don't think anybody doubts the ability to do Earth paleomagnetism and I'm happy that we can do it for space, too."

This research is described in a paper published Oct. 11 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.